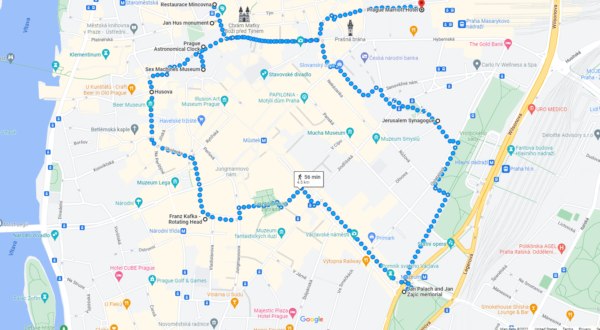

Even though I spent considerably less time taking a few photos of the Jan Hus Monument in Old Town Square than you did reading my previous post, I still had a busy day on tap trying to tick off as many sites as I could from the long list I’d assembled before I left the States on my only “Todd-frugal” free time in Prague. Here’s the ground I managed to cover courtesy of Google Maps.

But first a surprise.

I knew my route was going to be rather circular so I set out for the farthest point first – the quite understated memorial to Jan Palach. (You can see the Hus Monument in the upper left of the map and Jan Palach in the lower right.) Of course I missed a turn or two and as I was walking a particular building caught my eye.

It surprised me not only for its striking architecture but because I knew I was surprisingly distant from the Jewish Quarter. I took the picture not knowing anything about it other than being a synagogue. Here’s what I learned when I got home.

This is the Jubilee or Jerusalem Synagogue. It’s called Jubilee in honor of Emperor Franz Josef the First though it’s generally called Jeruzalémská synagoga because that’s the street it’s on. It was built as a consolidation of three synagogues in the Jewish Quarter that had been razed during the execution of the 1893 Sanitation Laws (a point I’ll discuss in more detail when we tour the Quarter Sunday morning.) The Jewish architect, Wilhelm Stiassny, born in Bratislava, made the bold choice to combine Art Nouveau with the Moorish Revival style that was fading from popularity at the time the building was constructed in the early 20th century. The still active synagogue is open to the public for tours. I declined the opportunity.

Jan Palach.

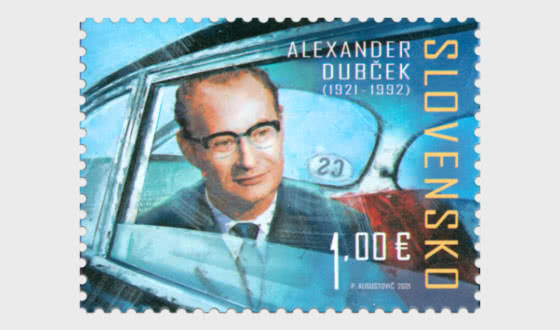

As the Habsburg Empire began to collapse, a sizeable group of provinces – Bohemia, Moravia, Czech-speaking Silesia, Slovakia, and Subcarpathian Ruthenia officially united on 28 October 1918 to become the nation of Czechoslovakia. After World War II, the country was part of the Soviet communist bloc. In 1953, Antonín Novotný succeeded Klement Gottwald as Communist Party Chairman and held the position as de facto ruler of Czechoslovakia until 5 January 1968 when Alexander Dubček succeeded him.

Unlike his predecessors who were strict Stalinists, Dubček

intended to govern through a policy he called “socialism with a human face.” Confronting a struggling economy and succeeding an unpopular regime, he began to eliminate its most repressive features. He lifted media censorship, allowed greater personal freedom of expression, and the existence of political and social organizations not under Communist control. These steps toward liberalization – including decentralization and a promise of autonomy for Slovakia – led to a period called the Prague Spring.

Dubček was wildly popular with students who took to the streets to celebrate and to press for continuing reform. Most of the public also supported Dubček giving him a 78 percent approval rating. His policies were far less popular, however, with remaining hard line elements within the Czechoslovak Communist Party and other party leaders in the Warsaw Pact nations who spent months trying to contain the reforms. On 20 August 1968, between 200,000 and 600,000 Soviet led Warsaw Pact troops accompanied by 20,000 tanks entered the country and were occupying Prague the following day. Although Dubček nominally remained the leader for another eight months, the Prague Spring effectively ended on that August night and the seeds of his vision wouldn’t sprout again for another two decades.

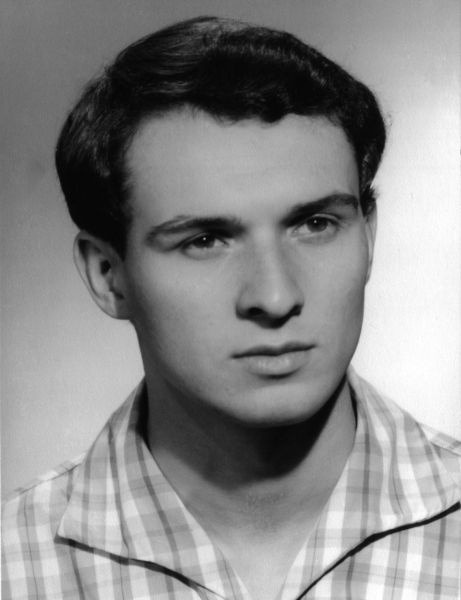

Jan Palach

[Photo of Jan Palach from Wikimedia Commons – Public Domain.]

was one of the students who had taken to the streets in the spring of 1968 and he turned his energy to protesting the Soviet led invasion in the fall and winter. Dismayed by the apathy he saw among the public, Palach planned an inconceivable act intended not as an act of protest but one of inspiration. On the night of 16 January 1969, Palach climbed to the top of Wenceslaus Square and, calling himself “Torch Number One” lit himself on fire. He died in a hospital three days later.

Palach both predicted and discouraged copycats. In one letter he warned Czech leaders that until they reinstituted reforms, others would follow his example. In a suicide note, he explicitly stated that he didn’t want others to follow his example. Nevertheless, between January and April 1969 Czech authorities reported at least 26 attempts at self-immolation.

Palach was initially buried at Olšany Cemetery (the historic cemetery I was unable to visit) and his funeral on 25 January turned into a massive anti-Soviet demonstration.

[Photo of Jan Palach’s grave from Wikimedia Commons – By Přemysl Otakar – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0].

Through his sacrifice, Palach remained so much a focal point of antigovernment protests that in October 1973, the Secret Police exhumed and cremated him. They gave his ashes to his mother but patrolled his gravesite forbidding anyone to place any sort of acknowledgement. (His ashes were returned to Olšany in 1990.)

Palach’s legacy continues and on the 20th anniversary of his sacrifice, during what became Jan Palach Week from 15 to 22 January 1989, there were repeated demonstrations against the totalitarian regime. One of the people arrested in Wenceslaus Square was the poet and playwright Václav Havel who would become Czech president on 29 December of that year. Today, at the top of the square behind the statue of Saint Wenceslaus and in front of the Národní Muzeum, if you look down you will see this memorial to Jan Palach.

(As we will learn, this isn’t the only place in Prague Palach is recognized.)

Kafka the First.

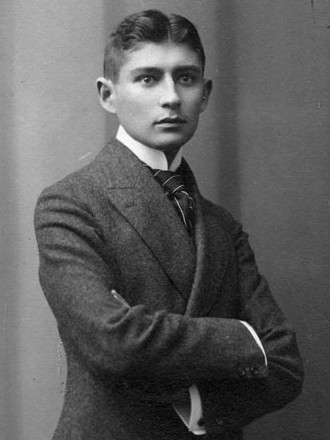

I think it’s fair to say that the name Franz Kafka has a place among famous Czech writers. And yet, while one of his most well-know stories – The Metamorphosis – (perhaps better translated as The Transformation) was published while he was alive, it’s fair to say that at the time he would have made no one’s list perhaps other than that of his friend and literary executor Max Brod.

Franz Kafka was born in Prague’s Jewish Quarter in 1893 to an authoritarian and domineering father whose personality often seemed to be lurking in the dark back corners of Kafka’s writing. His father sent him to German rather than Czech schools hoping to better his social standing.

Certainly, Kafka suffered from enormous self-doubt – not only regarding his writing – but also regarding his intellect and physical appearance.

([hoto of Franz Kafka from Wikimedia Commons – Public Domain.]

The psychologist Joan Lachkar calls The Metamorphosis a “model for Kafka’s own abandonment fears, anxiety, depression, and parasitic dependency needs. Kafka illuminated the borderline’s general confusion of normal and healthy desires, wishes, and needs with something ugly and disdainful.”

It’s with these aspects of his personality in mind that Czech artist David Černý, created the mirrored kinetic bust of Kafka composed of 42 different reprogrammable layers that rotate individually, using gears inspired by traditional Czech clockwork. (I don’t know if it’s ironic or deliberate but Prague’s Lego Museum is barely 200 meters from this work of art.)

(You can see a brief video with the day’s other photos here.)

Moving from one Černý sculpture to another, my next stop was “Man Hanging Out.” This wildly realistic work is easily missed if you fail to look skyward at the intersection of Husova and Skorepka. The work is meant to portray Sigmund Freud (who was born in Příbor – called Freiberg at the time) grappling with his fear of his own death. (The Ukrainian flag is not part of the installation.)

Till the end of the day.

I made two more stops – one planned and one unplanned – before calling it a day, grabbing a meal so little distinguished that it merited not a single note in my journal, and heading off for the clarinet final of the Prague Spring International Music Competition at the remarkable Rudolfinum (about which I’ll have some interesting history to relate).

I’ll discuss the planned stop in the next post. On my way there, however, I wandered past a storefront art gallery. I paused at the window and one of the owners / artists beckoned me in. As far as I could gather, she and her husband owned the shop and produced all of the art in it.

The two souvenirs I typically bring home from my travels are a hat and some locally produced art. Much as I had found a hat on my last day in the Algarve, I discovered two small paintings that seemed particularly appropriate as a remembrance of this trip on my penultimate day in Prague. They fit nicely in my suitcase and I had them framed after I returned home. I hung them in proximity to but not adjacent to each other as they are in the photo.

In my next post, I’m going to take you on a visit to a small but unique museum. See you then.