Here’s a reminder: I’m an American who was born and raised within certain parameters of Jewish tradition and who has turned away from any religious belief or practice. Thus, I hope you can forgive my ignorance about the 15th century Czech religious reformer Jan Hus. I’ve mentioned Hus and the Hussite War in previous posts but his importance is such that he requires a more in depth look. And I didn’t have to go far from lunch to meet him because this memorial

occupies a large space in Prague’s Old Town Square.

A few words about the memorial.

Ladislav Šaloun’s Art Nouveau Symbolist statue was officially unveiled on 6 July 1915 – the 500th anniversary of Hus’ death. In it Hus is standing above a burning stake (the means of his execution) looking toward the Gothic Church of Our Lady before Týn (not visible in the photo) that served as the main church of the Hussites from 1419 until 1621.

The monument seems to commemorate two wars centuries apart – the Hussite wars of the 15th century and the Bohemian Revolt against the Habsburgs that began in 1618. Although that war ended in 1620, it was among the triggers of the Thirty Years War that ravaged Europe. Hussite warriors from the first war stand on one side of Hus. On the other are people who were exiled after the Bohemian revolt failed.

Jan Hus and the Hussites.

I know this sounds like it could be the name of a Czech rock band but it’s not. Jan Hus was one of two significant proponents of the reformation of the Catholic Church who antedated Martin Luther by more than a century. The first was the Englishman John Wycliffe who died in 1384 when Hus would have been in his early teens. (While generally given as 1369, Hus’ true birth year isn’t known and could have been as late as 1373.) Hus is the other. He was executed nearly seven decades before Luther’s birth.

The young Hus is referred to as Jan syn Michalův (Jan, son of Michael) and his adopted surname comes from Husinec, the town of his birth. His mother taught him to read using the Bohemian Bible and encouraged him to enter the priesthood as a path out of poverty.

[Jan Hus by Gemaelde from duke.edu – Public Domain.]

Hus enrolled at the university in Prague and by 1396 had earned a Master of Arts degree. He was ordained as a priest in 1400. In 1402 the Czech masters of Charles College chose him to be the preacher at Bethlehem Chapel.

Sometime in this period, possibly as early as 1398, Hus first read Wycliffe’s writings. Many of these – such as rejecting transubstantiation, the claims of the papacy, and Wycliffe’s support for secular lordship over territorial churches free from papal control resonated with Hus. When he began preaching some of these reformist ideas at Bethlehem Chapel, he drew the sort of notice that for some might be unwanted.

As Czech speaking Bohemians – who had a pre-established tradition of reform efforts – drew closer to Hus’ preaching and Wycliffe’s writings the German faculty at the university in Prague issued a 1403 condemnation of 45 articles Wycliffe had written.

[Drawing of Hus preaching from Wikimedia – Public Domain.]

This was a manifestation of a broader political schism within Bohemia where Czech speakers had begun seeking independence from their Habsburg supporting neighbors. The effort at condemnation failed. It failed again five years later when Archbishop Zbyněk of Prague compelled the Czech University masters to again condemn the 45 articles.

In fact, this second attempt fueled Czech resistance. With Czech nationalists in tow, Hus found himself at the head of an effort to reform the Bohemian church. In 1409, Hus’ group prevailed upon King Wenceslaus IV to issue the Kuttenberg Decree granting Czechs complete control of the university faculty in Prague. The Germans all left for other universities and the faculty elected Hus as rector in that year.

This didn’t sit well with Archbishop Zbyněk who, in 1409 had Pope Alexander V issue a papal bull not only condemning Wycliffe’s teachings but prohibiting preaching them in Hus’ Bethlehem Chapel. Hus ignored the bull and continued preaching. When Alexander died suddenly in early May 1410, he was replaced by John XXIII a Pisan who is considered an antipope.

[Archbishop Zbyněk from Wikimedia Commons – Public Domain.]

Hus appealed to John XXIII to rescind the bull of Alexander. Zbyněk responded by excommunicating Hus.

In August 1410, following his local excommunication Hus was referred to Rome for disobeying ecclesiastical superiors. He refused to stand trial in Rome and was subsequently excommunicated by the Roman court in February 1411. This only increased his popular support with many in Bohemia and it was Archbishop Zbyněk who had to flee Prague.

You’re not the Pope. I’m the Pope.

Here the story gets a little confusing for the ostensibly Jewish boy who’s about to take a stab at understanding centralized church leadership and the relevant claims and machinations. First, we need to step back in time to 1378 and the onset of the Western Schism to gain some context for some of the claims and counterclaims that would lead to convening the Council of Constance and ultimately Hus’ execution there.

In 1309, the papacy was located in Avignon (I don’t know about the bridge) but by the early 15th century many viewed it as corrupt. Pope Gregory XI who was temporarily in Rome died on 27 March 1378 before he could return to Avignon. Gregory was replaced by Pope Urban VI but many of the cardinals who elected Urban came to regret their decision, left Rome, and, six months later, elected a “new” pope in the person of Clement VII.

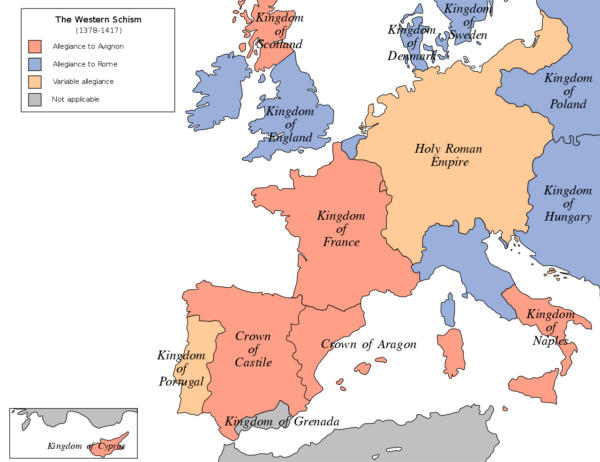

Clement wasn’t very popular in Rome so he returned to Avignon. But now we had a problem. For the first time, the College of Cardinals had elected two different popes giving each faction a legitimate claim to the papacy. This then spilled over into the secular realm because secular rulers had to choose which pope to recognize in case issues of suzerainty arose in international relations.

The situation worsened in 1409 with the Council of Pisa which had elected first Alexander V and then John XXIII. The mishmash of loyalties looked something like this.

[Map from Wikipedia File – Grand schisme 1378-1417.svg, CC BY-SA 3.0].

Off to the Council of Constance

The situation was heated and there were a lot of shifting loyalties. This prompted Sigismund of Hungary to convene the Council of Constance (1414-1418) to resolve the schism, to address errors in the faith, in particular the movement in Bohemia led by Jan Hus, and to reform the church hierarchy.

Thinking, “We can work it out,” Sigismund gave Hus a promise of safe-conduct to Constance so he could explain his teachings.

[Sigismund of Hungary from Wikimedia Commons – Public Domain.]

This promise meant he couldn’t be imprisoned or otherwise harmed. Hus arrived in Constance in early November 1414 and began preaching to the people of the city. Catholic officials cited this as a violation of his safe-conduct pass and had him arrested. At his hearing, Hus said he would recant if proof of any error came from scripture as opposed to church teachings. The Council ignored this offer, turned him over to secular authorities, and he was burned at the stake on 6 July 1415. This ignited public fury and led to

The Hussite Wars.

The Bohemian Reformation that started in Prague in the last half of the 14th century would soon boil over into outright conflict with the execution of Jan Hus. That was followed less than a year later by the execution of another leading Hussite, Jerome of Prague by the same Council of Constance.

Over the ensuing three years, many adherents of Hus’ teachings – now officially known as Hussites – were imprisoned. In 1419, the priest Jan Želivský organized a procession through Prague in opposition to the town council’s decision not to release Hussite prisoners.

[Procession of Jan Želivský from Wikimedia Commons – Public Domain.]

At some point, stones were hurled from the town hall windows at the protesters. Allegedly, one of them struck Želivský, who responded by leading his followers into the building and hurling seven town council members out the upper story window to their deaths – an event known as the First Defenestration of Prague.

Some deem this the first battle of the Hussite Wars but the first true engagement was the Battle of Sudoměř where the Hussites, led by a brilliant military strategist, Jan Žižka, emerged victorious. Žižka led Hussite forces against three crusades and never lost a single battle.

The wars continued off and on for 15 years finally ending on 30 May 1434 when a group of moderate Hussites known as Utraquists joined with Catholics to rout the more radical Taborite Hussites at the battle of Lipany.

Martin Luther, although not directly influenced by Hus, declared after reading Hus’ magnum opus De ecclesia in 1520, that he, his prior Johannes von Staupitz, Saint Augustine, and even Saint Paul were “all Hussites.”

The next post takes us to a memorial for a modern Czech martyr – Jan Palach.