I could only hope that the sun that greeted us Monday morning – by far the brightest start to any of my three days in Vienna – portended a day of equal quality. Earthbound’s schedule had only a tour of the Upper Belvedere with the option to visit the Lower Belvedere (separate admission) in our free time. Here’s a look at the complex from goodieline on Pinterest with the Lower Belvedere at the top of the photo.

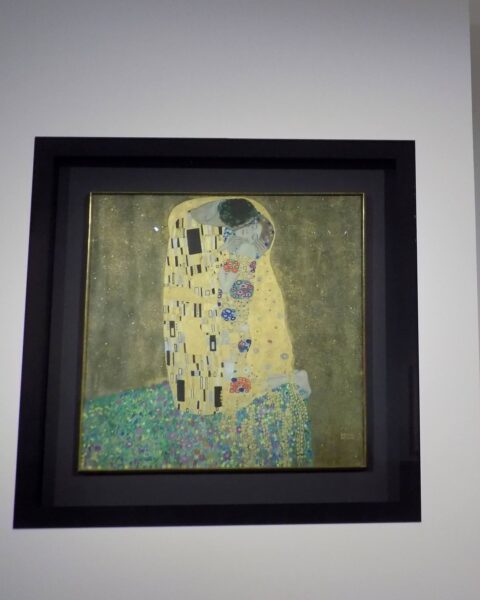

If you’re a fan of Gustav Klimt, the Upper Belvedere should be on your “places I must visit if I’m ever in Vienna” list. Of the 420 works currently on display as part of the permanent collection, 24 are by Austria’s most famous painter including Judith (a forgery of which I’d seen at the Fälschermuseum yesterday) and, his most famous painting, The Kiss. But once again I’m jumping ahead.

Stompin’ with Prince Eugene of Savoy.

From the time he was a boy growing up fatherless in France, Prince Eugene of Savoy wanted a military career. In 1683 a few months before he turned 20, Eugene heard about the Ottoman siege of Vienna and implored King Louis XIV to allow him to join the battle. Louis denied the request so Eugene secretly left Paris, traveled to Vienna, and pledged his allegiance to Leopold I who would serve as Holy Roman Emperor for 46 years and nine months – longer than any other of the Habsburgs. And Prince Eugene played a substantial role in that. (As Shlomit often reminded us, the HRE was neither truly holy, truly Roman, nor truly an empire but that’s a tale for another time.)

Eugene quickly proved himself an exceptional soldier and tactician. He joined forces with John III Sobieski of Poland that lifted the siege and marked the beginning of the end of Turkish rule in Europe. By 1687, Eugene had risen to the rank of lieutenant general, to field marshal in 1693, and in 1697 he was appointed supreme commander of imperial forces in Hungary. Following his victory at the battle of Zenta on 11 September 1697, Leopold rewarded Eugene with honors and estates that Eugene combined with spoils he’d collected from that battle to become one of the richest men in Europe.

Eugene continued amassing property and, after eight years of terracing, began construction of the Lower Belvedere.

Although it was outside the city walls at the time, the Lower Belvedere became one of his residences when it was completed in 1717. Soon thereafter he began work on the Upper Belvedere which served mainly as a venue for the Prince to entertain the elite of Vienna.

Both buildings and the gardens stand as resplendent gems of baroque architecture and design. Visit the Upper Belvedere today and you can see not only the extensive collection of Klimt paintings but also art from the Middle Ages, Baroque, Classic, and Biedermeier periods. Several rooms have been restored with the most important of these being the Marble Hall

where, on 15 May 1955, – a decade plus one week after VE Day – the foreign ministers of Britain, France, USSR, and USA signed the treaty restoring Austria’s sovereignty. Austrian foreign minister Leopold Figl, who was the last to sign, carried the document onto the balcony, waved it in front of the large crowd, and proclaimed, “Österreich ist frei!” (“Austria is free!”)

The Museum of Military History and the Nobel Peace Prize.

Having been guided by Martha through some of the Klimt and other works at the Belvedere, I was ready to head out to grab some lunch and make a quick stop at the Museum of Military History. I know this seems like a strange choice for me but it houses one very specific item I wanted to see. And that was

this car. In case you can’t tell from the photo behind it, this was the car in which the Archduke Ferdinand and his wife Sophie were riding when they were assassinated near the Latin Bridge that I’d visited

in Sarajevo. It felt a little like closing a circle.

It was just a single stop on the D tram from the Belvedere to the Swiss Garden where I found a bench and watched people wander through the park as I ate a kebab and fries from one of Vienna’s seemingly ubiquitous kebab kiosks. (It seems that when I’m traveling out of the U S, I’m inclined to eat a kebab if one is readily available probably in memory of my time in Moscow with Erin.) From there it was a short walk to the museum.

While I paid little attention to the statuary as I rolled through the hall of Kaisers,

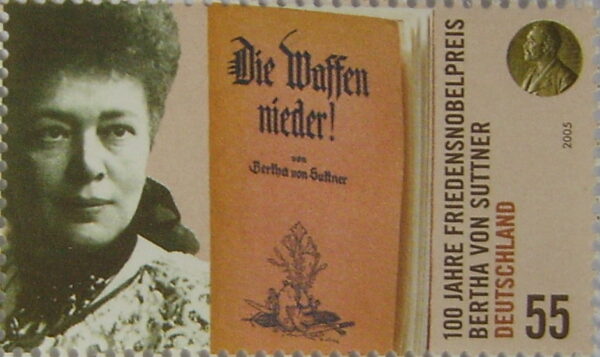

I was drawn to one exhibit where I picked up, what was for me, a new bit of historical knowledge. It was the story of Baroness Bertha Felicie Sophie von Suttner (nee Kinsky). Not only was she the first woman to win a Nobel Peace Prize (and the only woman until 1975 who didn’t have to share it with a man) but the Peace Prize itself likely wouldn’t exist had it not been for her. Here’s how it happened.

Bertha’s father died shortly before she was born so, though her mother was with her, she was raised near Brno under the oversight of a member of the Austrian military at the imperial court. There she was intellectually reared on a diet of literature and art but within a militaristic construct.

[Photo of Bertha von Suttner from Wikimedia Commons – Public Domain.]

When she turned 30, she left her mother’s care to take a job with the Suttner family as a sort of governess to their four daughters. This is where she met her future husband Arthur who was seven years younger than she.

Arthur’s disapproving family encouraged Bertha’s application to work for “a very wealthy, cultured, elderly gentleman, living in Paris, who desires to find a lady also of mature years, familiar with languages, as secretary and manager of his household.” She moved to Paris when she was offered the position. The ‘elderly’ gentleman was 42 year-old Alfred Nobel.

She remained in that job for a mere eight days before returning to Arthur after receiving a passionate letter from him. They married in secret and spent the following nine years in Georgia where they gradually became involved with a growing European peace movement mainly through the International Arbitration and Peace Association based in London. They returned to Suttner’s family in 1885. For Bertha, although her employment with Nobel had been brief, it must have made a deep impression on him because their relationship lasted until his death in 1896.

Bertha began writing novels into which, like those of Harriet Beecher Stowe, she wove her idealistic goals. This writing culminated in her 1889 novel Die Waffen nieder (Lay Down Your Arms) that became one of the most influential books in late 19th century Europe.

[Bertha von Suttner and her book from Wikimedia Commons – Public Domain.]

Her activism and writing earned her the sobriquet “Generalissimo of the Peace Movement.” And rightly so. In 1891 alone, she aided in forming a Venetian peace group, founded the Austrian Peace Society serving as its president for many years, and attended her first international peace congress. Suttner saw a single Europe as the only way to build and maintain a lasting peace on the continent.

Throughout this time she also continued corresponding with Nobel keeping him informed of the progress of the peace movement. He didn’t completely believe in her movement once writing to her,

Perhaps my factories will put an end to war even sooner than your peace congresses. On the day when two armies will be able to annihilate each other in a second, all civilized nations will recoil with horror and disband their troops on knowing that total devastation will be in store for them if they engage themselves in war.

However, Nobel wasn’t single minded in this notion. At another time he wrote, “Inform me, convince me, and then I shall do something great for the movement.” Apparently, she did. In January 1893, Nobel wrote to Suttner revealing his plans to establish a peace prize. It was first awarded with the other Nobel Prizes in 1901. After four unsuccessful nominations Suttner won hers in 1905.

Bertha von Suttner died on 21 June 1914. A week later, Gavrilo Princip succeeded in assassinating Archduke Franz Ferdinand near the Latin Bridge in Sarajevo providing the excuse for belligerent action that European imperial powers had sought for decades. Exactly one month later on 28 July 1914, Austria declared war on Serbia and began shelling Belgrade shattering Baroness von Suttner’s dream of a single Europe for 78 years until the signing of the Maastricht Treaty in 1992.

Scofflaw!

I won’t mention on which tram or Metro ride, whether to the Military Museum from the Belvedere or from Museum to the stop nearest the hotel, (perhaps both!?) but at some point during the day my transit ticket expired, I took the risk, and became a public transit scofflaw in a fourth European capital city. Now that I’ve confessed, you can find all my photos from the morning here.