The Winter Games Finally come to Canada.

If you’ve read the Lillehammer tales, you already encountered two stories from the Calgary Olympics – the tragedy of Dan Jansen and the triumph of Bonnie Blair. Fortunately, there was more to the first Winter Games held in Canada than just those two stories. The first of those might be Calgary’s desire to host the Winter Games. In 1957, a group of local sportsmen gathered to put together the city’s initial bid to host the 1964 Games. They were awarded to Innsbruck, Austria. The IOC rebuffed Calgary’s second attempt for 1968 choosing to send those games to Grenoble, France. Then Sapporo, Japan got the nod for the 1972 Games.

But after shelving the idea for a few years, local persistence paid off and a reorganized Calgary Olympic Development Association (CODA) put forth a bold bid brushing aside the city’s lack of infrastructure and proposing to construct all new venues that would then serve as training grounds for future Canadian athletes. This convinced enough members of the IOC to award the Games of the XV Winter Olympiad to Calgary – a venture that would, at a cost that exceeded $800 million Canadian dollars, become the most expensive Winter Olympic Games to that date.

(The CODA plan has worked well for Canadian athletes. The host country won only five total medals – three silver and two bronze – in 1988. Canadian medal totals gradually increased to seven in 1992, 13 in 1994 and has not dropped below 24 since 2006 including 26 at Beijing 2022.)

Did you say torch reel-eh?

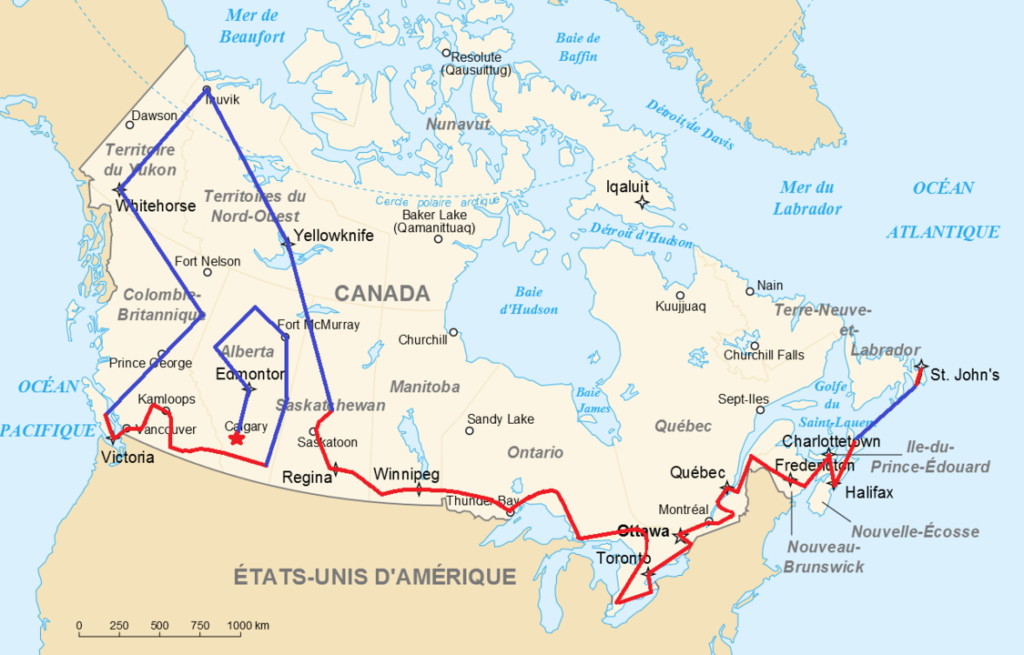

Starting in Newfoundland,

[Map of torch relay from Wikipedia By Christophe Badoux – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0.]

the torch traveled 18,000 kilometers in Canada – 11,000 on the ground and 7,000 by other means of transport. The route, which took the torch to Inuvik north of the Arctic Circle, was designed so that the time spent in each province and territory was proportional to the resident population. Twelve year old Robyn Perry, representing the next generation of athletes, lit the cauldron.

Why settle for one mascot?

Although many Olympic Games – both Summer and Winter – have had multiple mascots, the practice started at Calgary in 1988. First the Canadians needed to choose a mascot. They settled on polar bears because they’re symbolic of the Arctic region and not only do they not hibernate, they’re active through the winter. But one bear wasn’t enough and so were born

[Mascot photo from calgarystampede.]

the brother and sister duo Howdy and Hidy (seen here with the Calgary Stampede’s Harry the Horse). Their names, representing typical western greetings came from a contest sponsored by the Calgary Zoo.

A few other facts.

A record 57 National Olympic Committees participated in the Calgary Games. Fiji, Guam, Guatemala, Jamaica, the Netherlands Antilles, and the Virgin Islands made their Winter Olympics debuts.

The Calgary Olympics were the first smoke-free Olympic Games.

When not competing or training, athletes were encouraged to sit in the stands with public spectators.

Curling appeared as a demonstration sport while freestyle skiing and short-track speed skating were demonstration disciplines. All three were added to the Olympic program in Nagano in 1998.

For the first time, speed skating was held on an indoor rink.

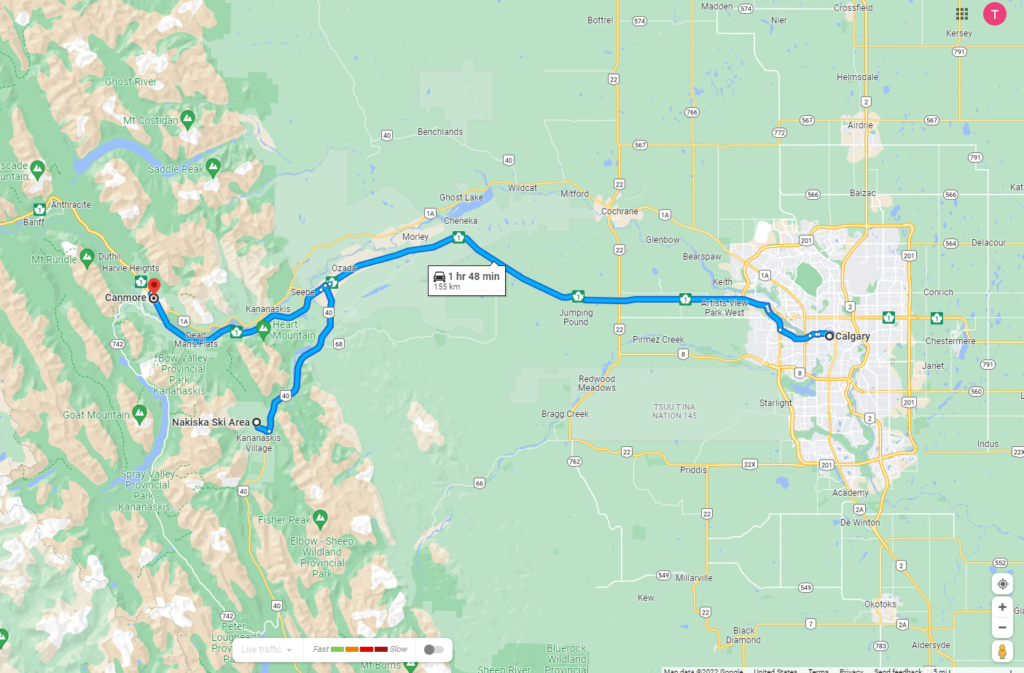

Alpine skiing was held at Nakiska while biathlon and cross-country skiing competitions took place in Canmore.

[From Google maps.]

Nakiska didn’t have enough snow so the Alpine skiing competition was held on artificial snow for the first time.

Noteworthy athletic achievements.

In the “Battle of the Carmens” in women’s figure skating, Katarina Witt defended her 1984 gold medal. Witt and American Debi Thomas were the gold and silver medalists in the 1987 world championships and had independently chosen music for their free skate from Bizet’s opera Carmen. While Thomas became the first African-American woman to win a medal at a Winter Games, Canada’s Elizabeth Manley outjumped Thomas to capture the silver.

Men’s figure skating was known as the “Battle of the Brians” reflecting the competition between the Brian Boitano of the U S and Canada’s Brian Orser. Boitano edged Orser for the gold by virtue of his higher technical merit score. After 1988, artistic impression became the tiebreaking factor.

With her pair of bronze medals in downhill and Super G, Canadian Karen Percy replaced Nancy Greene, the country’s only other female skier to win two medals at one Olympics and became the nation’s new Alpine Queen.

Finland’s Matti Nykänen was the most successful male athlete at Calgary winning three ski jumping gold medals (Normal hill, Large hill, Team).

Dutch speed skater Yvonne van Gennip matched Nykänen’s three gold medals winning the 1,500, 3,000 and 5,000 meter races. Unless the IOC again changes the Olympic cycle, Christa Rothenburger of the GDR accomplished a feat that will never be duplicated. She set a world record to win gold at 1,000 meters in speed skating. Then, seven months later in Seoul she won a silver medal in sprint track cycling becoming the first athlete to win a medal at the Summer and Winter Games in the same year.

Definitely last but certainly not least.

The Jamaicans.

The attentive among you surely noticed that Jamaica was among the countries making their Winter Games debut. And those of you with good memories for sports, movies, or both might already be thinking about the Jamaican bobsleigh team. Yes, this was the debut of the group made famous in the highly fictionalized film Cool Runnings.

Jamaicans competing in a local event called a pushcart derby inspired George Fitch, the Commercial Attaché for the American embassy in Kingston, to envision putting together a Jamaican bobsleigh team. Facing a public disinterested in the call for volunteers, the Jamaican Defense Force convinced some of its enlistees to step up. Dudley Stokes, Devon Harris, and Michael White emerged from that pool as the first members of the team with a fourth man, Caswell Allen added later. Stokes, a helicopter pilot became the driver.

With Fitch providing most of the funding, the International Bobsleigh and Skeleton Federation agreed to hold a slot open for the Jamaican team. However, the IOC still tried to disqualify the team shortly before the Olympics until a number of famous people including Prince Albert of Monaco, stepped in. The IOC caved.

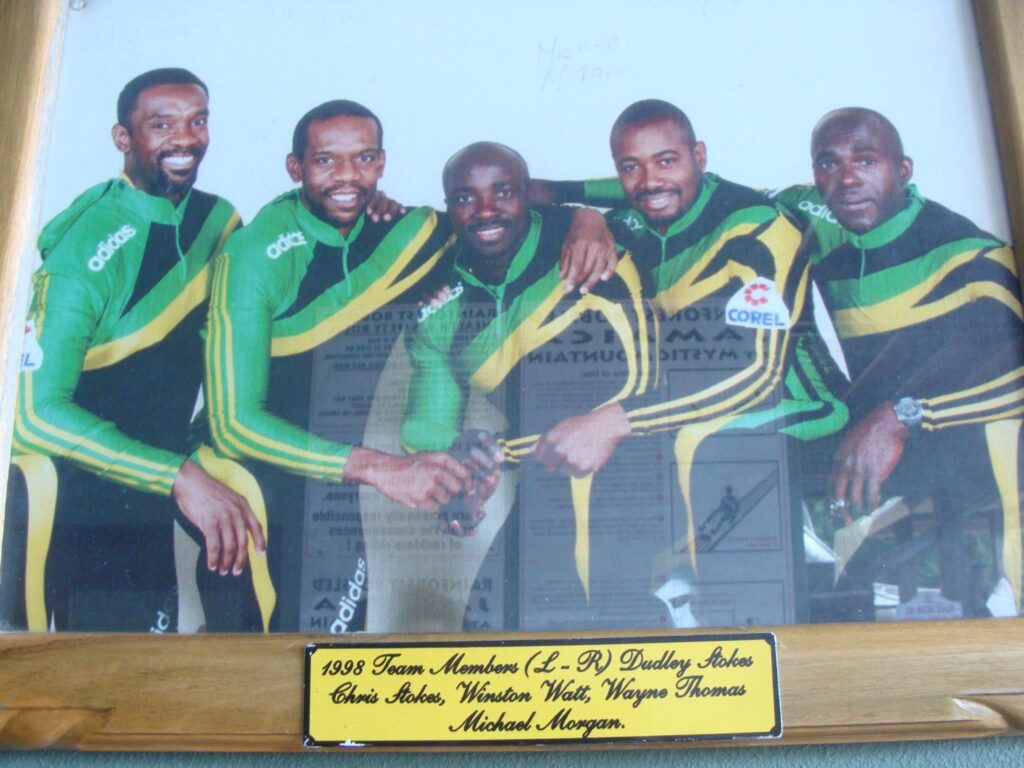

[Photo of Jamaican bobsleigh team from Pinterest Idoislandweddings.]

Competing in the two-man bobsleigh, Stokes and White became Jamaica’s first Winter Olympians and after the first two runs, they were a respectable 22nd. Unfortunately, they faltered on the final two runs and dropped to 30th among the 41 teams.

Still, they’d done well enough to feel they could compete in the four-man but they had two immense obstacles to overcome. First, they didn’t have a sleigh so they sold t-shirts to raise the funds to buy a sleigh from the Canadian team. The second was that Allen suffered an injury in training and couldn’t compete. Undaunted by the fact that he had never been in a bobsleigh the team recruited Dudley Stokes’ brother Chris to replace Allen.

Displaying great athleticism, the team was 24th of the 31 competing teams after the first two runs. Then came the third run and the crash dramatized in the film as an equipment failure. In truth, it was a combination of excess speed and driver error that caused the crash in the ninth turn called the “Kreisel.” Also, the team pushed the sleigh to the finish rather than picking it up and carrying it as the film depicts. They didn’t compete in the final run and finished last with a DNF.

The Englishman.

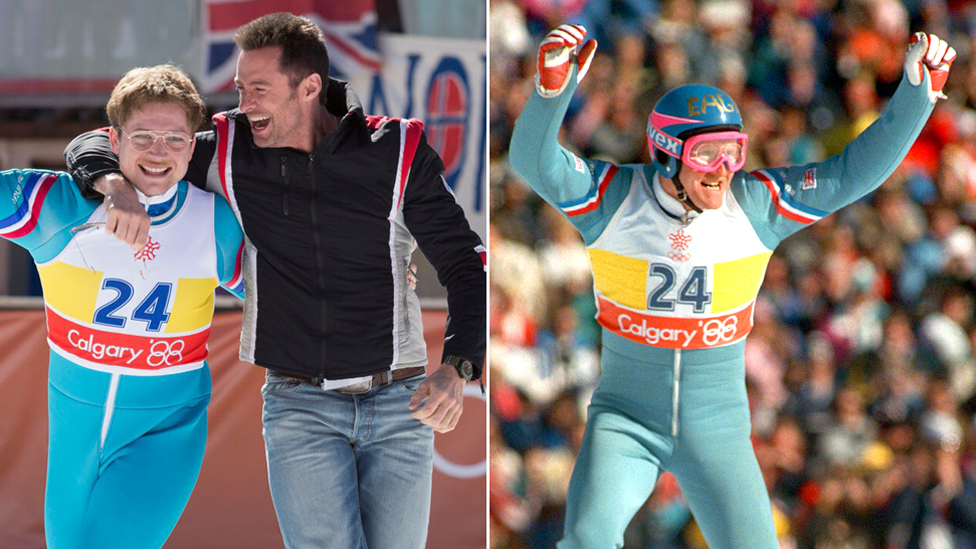

The Calgary games featured one other losing competitor whose fame far outstripped his athletic achievement. Like the Jamaicans, his story also made it to the big screen. It was a biopic of Michael Edwards called Eddie the Eagle.

Representing Great Britain at the 1987 world championship, Edwards placed 55th. This finish, combined with his best jump exceeding 65 meters (a minimum that the British Ski Federation had increased four times in an effort to keep him out of the Olympics) and a British Olympic Association policy that the best performing athlete in a given sport has the right to go to the Olympics earned his spot on Team GB.

Edwards was a failed Alpine skier who moved to Lake Placid, New York to complete the switch to ski jumping so he could continue chasing his dream of reaching the Olympics. He managed to overcome a lack of funding, being slightly overweight (nine pounds heavier than the next closest competitor), and nearsightedness that frequently fogged his glasses and impaired his vision.

At the Olympics, he finished 58th the normal hill with a total of 69.2 points a mere 71.2 points behind the 57th place finisher Bernat Sola of Spain and 159.9 points behind Matti Nykänen’s winning score. On the large hill, Edwards again finished last 53.3 points behind the jumper from Canada who finished 54th.

[Photo from bbc.]

However, we shouldn’t scoff too much at Edwards’ jumps. His 71 meter jump on the large hill was a British record at the time and, more than 30 years later still stands sixth all time in that country’s history.