Notes on the XVII Winter Olympiad – Lillehammer 1994 (Nordic cities and Me addendum two)

As I’ve noted elsewhere, it seems that every Olympic Games has some degree of controversy attached to it be that a boycott, an athletic scandal, or a protest by the host city’s residents (think Vancouver for this one). But then there’s Lillehammer where the biggest element of controversy actually happened a bit more than a month before the games – and happened not in Norway but in Detroit when this incident – the infamous attack on Nancy Kerrigan by Shane Stant planned by Tonya Harding and Jeff Gillooly

turned one part of the Games into something of a media circus and left athletes like Bonnie Blair wondering, “Why are people here from the National Enquirer?”

For those who don’t recall the outcome, Kerrigan recovered in time to compete in the Games where she skated beautifully but was out dueled by Oksana Baiul while Harding skated poorly, had some drama with her skate laces, and finished eighth. Now that I’ve disposed of the circus, it’s time to focus on what Sports Illustrated described as “the fairy-tale games” and that ESPN writer Jim Caple called

The best Winter Olympic Games ever.

Most of my chapters about the Games themselves have included what you might call the “facts and figures” such as the number of participating countries and athletes, which countries won the most medals, which athletes had great or memorable performances, and so on. I’ll be doing the same about the Lillehammer Games.

I’ve also tried to find at least one interesting sidebar story for each Olympic Games while keeping these recaps below an upper word limit of 1,500 to make them more easily readable. And therein lies the Lillehammer problem. You see, while you can find stories from most Games that range from inspirational to heartbreaking, Lillehammer’s Games are all about the stories. So, readers, buckle up because this post is merely a prologue to a series of Lillehammer tales.

Winners, losers, and numbers.

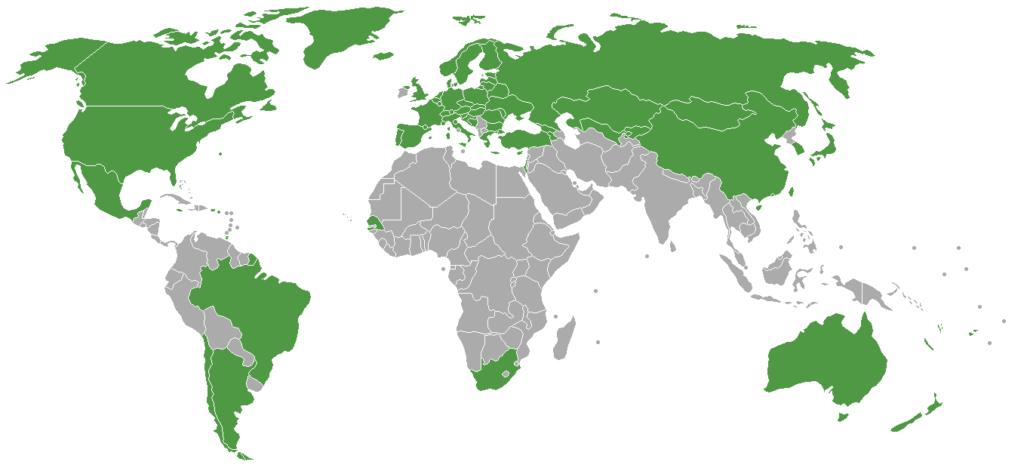

A record 67 National Olympic Committees sent a total of 1,737 athletes to compete in 61 different events. American Samoa, Israel, and Trinidad and Tobago made their Winter Olympics debuts.

[Map from Wikimedia Commons BY Ivan Ogareff – Own Work CC BY-SA 4.0.]

In 1993 Czechoslovakia had split into the independent nations of Slovakia and the Czech Republic so these new countries made their first appearance independent of one another. The same is true for Russia, and the former Soviet Republics of Armenia, Belarus, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Moldova, Ukraine, and Uzbekistan following the 1991 breakup of the USSR. But perhaps the most remarkable first time participant was Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Unlike the 1952 Oslo Games, the reigning monarch King Harald V, officially opened the Lillehammer Games.

Either Russia or the host nation Norway topped the medal table depending on your sorting preference. Russia held an 11-10 edge in gold medals but Norway captured 26 total medals to Russia’s 24. Norway had the lone podium sweep capturing all three medals in the Men’s combined Alpine skiing event.

Italy’s Alberto Tomba (affectionately called Tomba la Bomba),

[Photo from Olympicachannel.com.]

who had dominated the slalom and giant slalom through the late eighties and early nineties but whose fortunes appeared to be waning after winning only a single World Cup Race in 1993, pulled off a phenomenal second run in the slalom to vault from 12th to second and win the silver medal.

In its preview of the Games, Sports Illustrated wrote, “all seven million Austrians and half the cows in Switzerland ski faster than the entire U S ski team.” They were not particularly prescient as Americans Tommy Moe and Picabo Street won gold and silver respectively in the men’s and women’s downhill.

Swiss skier Vreni Schneider won a complete set of medals by taking gold in the slalom, silver in the combined, and bronze in the giant slalom.

Italian Manuela di Centa dominated the women’s cross country events winning a brace of gold medals, a matching pair of silver medals, and a bronze.

With rules on professionalism changed and relaxed, Great Britain’s Jayne Torvill and Christopher Dean returned to the ice a decade after their breathtaking and gold medal winning interpretation of Ravel’s Bolero in the Sarajevo Games. They won a bronze medal in their farewell Olympic performance.

[Video capture from Mintaka Alnilam Channel YouTube.]

Myriam Bédard of Canada swept both gold medals in the women’s biathlon.

Repeat winners included the Swiss two-man bobsleigh team of Gustav Weder and Donat Acklin – the first to accomplish this feat, Russian pairs skaters Ekaterina Gordeeva and Sergei Grinkov repeated their 1998 title after skipping the 1992 Games in Albertville, and American Bonnie Blair made history by becoming the first woman to win three consecutive speed-skating titles in the 500m and by winning a second 500m/1000m double.

In his fourth Olympics, American speed skater Dan Jansen finally won a very elusive gold medal in the 1,000 meter race.

Local hero Johann Olav Koss set speed skating world records while winning gold in the 1,500, 5,000, and 10,000 meter races. He had also won gold in the 1,500 in Albertville in 1992.

[Photo from Newsbeezer.]

Participants in boldface above will each receive their own Lillehammer tale.

The collective Lillehammer tale.

Nearly three decades after the Lillehammer Games, they are still known as the “White-Green Games”. The smallest part of this had to do with the weather. Like Sarajevo a decade earlier, the winter in Lillehammer in 1994 had been practically snowless. Then, three days before the scheduled opening of the Games, the skies opened and deposited two meters of snow. The snow then stopped and, although the temperatures were almost frighteningly cold, the skies were blue and cloudless for the duration of the Games. That partly takes care of the white moniker.

The green element arose from the care in the design, planning, and materials chosen for the venues. The designers chose materials with an emphasis on solidity, honesty, authenticity, and environmental awareness. All the venues were built with a sensitivity to nature in mind and the hope that it would elevate the environmental awareness of the Norwegian people.

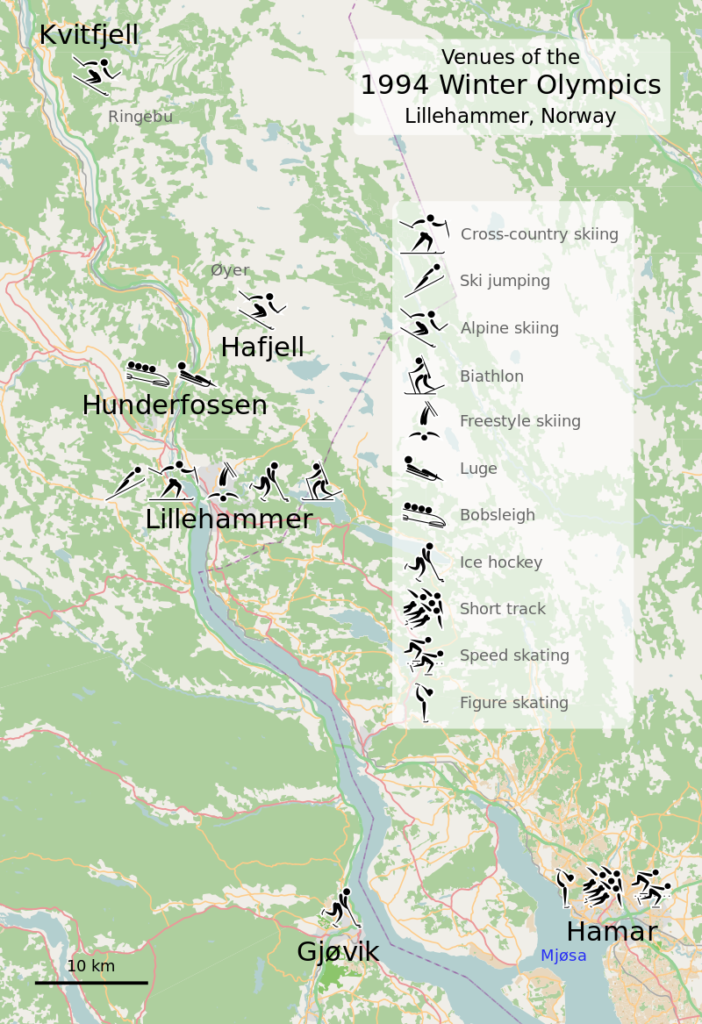

[Map from Wikimedia Commons by USER Arsenikk Map data from OpenStreetMap, pictograms created by User:Thadius856 Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0.]

In all, Norway constructed ten new venues for the 1994 Games and all remain in use today. Six of them – the Birkebeineren Ski and Biathlon Stadium, Lysgårdsbakkene Ski Jumping Arena, Håkons Hall, the Lillehammer Olympic Bobsleigh and Luge Track, as well as the Gjøvik Olympic Cavern Hall, and the concert hall at Maihaugen – still retain their certification under the Eco-Lighthouse keeping them at the forefront of sustainability efforts and demonstrating their continuing environmentally friendly operation.

In a final step, the designers wanted to reinforce the notion of Norway as the birthplace of winter sport. They created identifying symbols for each sport inspired by Norwegian petroglyphs. Each sport had a unique white figured pictogram on a magenta background.

[Image from graphicnews.]

The skiing pictogram drew its inspiration from a petroglyph discovered on the island of Rødøy in the municipality of Alstahaug in the northern part of the country. Its age is estimated at 5,000 years and it is the oldest known depiction of a human on skis.

[Photo from Smithsonian.]

In a sad coda in 2016, two boys one publication described as “well-intentioned but misguided” thought they could improve the glyph by scratching it into greater relief. The damage is irreparable an no one will again see it in its original state.

-

It’s just a shot away – Prizren

March 6, 2026 -

Some things looking better, baby – Getting into Kosovo

March 4, 2026 -

Here, where the sky is falling – Kukës

March 2, 2026 -

That’s when we fall in line ’cause we got Berat

February 27, 2026 -

Walking on the big stuff – a climb to Tragjas

February 25, 2026