Ice, ice, baby and then not.

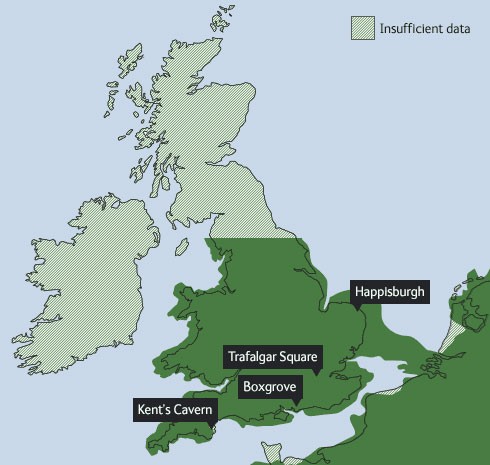

It should come as no surprise to any of you who are at all familiar with geology – even if that comes only from reading my brief sketches of that complex science – that Britain was once physically joined with its continental neighbor. In this instance, however, we needn’t retreat into the distant mists of early Earth to see the two as one. A mere 20,000 year spin in the WABAC Machine to the most recent period of great glaciation would drop us on a continent that looked something like the one in the image below from the UK’s Natural History Museum.

We could start our journey into Britain’s past here but that’s too recent for my taste. Instead, let’s go back about 500,000 years, grab our spyglasses, and try to spot a clan of Homo heidelbergensis possibly a common ancestor of both H. neanderthalensis and H. sapiens. Now we can peer out the windows of the WABAC and watch the passage of 100 millennia.

That’s right, 100,000 years but for us it’ll go by in two shakes of a lamb’s tail. In the first 50,000 years we’ll see the build up of the most severe glaciation of the past million years. Nearly all of northern Europe is buried under unthinkably thick ice sheets and the area comprising Britain too cold for any human ancestral species to survive. So, in this time we might see H. heidelbergensis migrate south.

By 400,000 years ago, the glaciers have thawed and as they did, a glacial lake ripped free and began carving the channel between Britain and mainland Europe. It failed to finish the job so a land bridge connecting East Anglia with the Netherlands remains.

[Map from UK Natural History Museum.]

By this time, the normal cycle of glaciation and interglacial periods had lengthened from about 41,000 years to 100,000 years. Also at about this time, evidence indicates that early Neanderthals began to occupy parts of southern Britain as migrants. As the climate changed through these periodic cycles, they’d return to the area around present day Belgium or slightly farther south in their own process of advance and retreat that continued for tens of thousands of years.

The original Brexit.

In the early years of the twenty-first century, the separation of the United Kingdom from its participation with the European Union – colloquially called Brexit – was a political battle fraught with controversy and animosity between participants on both sides of the issue and the channel. While the brouhaha over this Brexit was socio-political and economic in nature, it wasn’t the first time Britain broke from its continental neighbor. In fact, it wasn’t even the second time such a rift occurred.

This first split occurred about 125,000 years ago. The glaciers continued to melt. Sea levels rose to the point that they submerged the land bridge and parts of Norfolk and Lincolnshire. In fact, the climate was so warm that animals we think of as exclusively African were the principal residents of London. The WABAC can take us on a Thames Valley safari where we’ll see lions patrol the area that will become Trafalgar Square and hippopotamuses wading along the banks of the Thames.

[Image from historytoday.]

Obviously, these animals arrived before the sea levels isolated the island. It seems the Neanderthals had also retreated. The best current evidence is that the island had no humans for at least 60,000 years.

Britain rejoins Europe.

Perhaps the animals we consider tropical enjoyed their isolation during this 60,000 year period but Earth had other plans. The interglacial period was slowly ending. More water began to freeze and sea levels concomitantly dropped. However, unlike the period just prior to the enisling of Britain, rather than a narrow lathlike strip of land, a broad grass covered plain that stretched considerably east of Hapisburgh and well west of Plymouth and Cornwall created a single continent. This grassland also connected the then unpopulated islands of Britain and Ireland.

Fossil evidence indicates that about 60,000 years BP, Neanderthals reappeared on the island and h. sapiens joined them within 20,000 years indicated by a jawbone discovered in a cave near Torquay. But nature continued to be less than kind to these early human occupants eventually reverting to the conditions shown on the first map in this post. Between 25,000 and 20,000 years BP they deserted Britain once again.

The return of humans and the second Brexit.

Archaeologists have a name for the exposed land in the east that connected Britain with the mainland of Europe. It’s called Doggerland and they believe it looked like this:

[From University of Bradford Lost Frontiers Project.]

There’s considerable evidence that Mesolithic hunter-gatherer humans lived and traveled throughout Doggerland. However, they found themselves in an ever shrinking land area as the glaciers melted and sea levels rose between 20,000 and 8,100 years ago. As you can see from the above map, even by 8,000 BCE, the seas had reclaimed nearly all of Doggerland. The rising sea continued its process of gradual reclamation perhaps culminating with, for the few humans inhabiting the region, the catastrophic Storegga Slides.

The Storegga Slides were a rapid series of submarine landslides that occurred 100 kilometers or so west of Møre og Romsdal, Norway about 500 kilometers north of Bergen. An earthquake is the suspected cause of the Storegga Slides with two possible triggers. In one scenario a quake triggered the catastrophic expansion of methane hydrates weakening the stability of the seabed. The other proposes streams from melting glaciers amassing trillions of tons of sediment at the edge of the continental shelf with an earthquake collapsing a massive area of seafloor into the deep Norwegian sea.

This landslide triggered a massive tsunami with a 10 meter high wall of water traveling at perhaps 100 kilometers per hour and reaching 40 kilometers inland. It probably obliterated most of the coastal population and, although it wasn’t isolated for long, Britain had again split from the European continent. For the first time its inhabitants found themselves on an island.

From the Stone Age to the Iron Age.

The population of Britain appears to have remained sparse but evidence shows some trade and cultural exchanges throughout the Mesolithic and Neolithic eras between the new island and the continent of which it was once a peninsula. While various agricultural systems were developing through Mediterranean and Central Europe, even after the great tsunami the people of Britain remained mainly hunter-fisher-gatherers for thousands of years.

Farming was widespread across Europe by 5,000 BCE, but it appears to have taken an additional 1,000 years before there’s evidence of significant agriculture in Britain. Work on Stonehenge

[Image from bbc.]

likely began about this time and continued for another 2,500 years as humanity passed through the Stone Age and Bronze Ages and eventually into the Iron Age. Being an island was of little protection from invasion and attempted invasion for the now growing population however. Curiously, recent genetic analyses show that the earliest farmers from Europe likely sailed along the coast of Portugal and France from Iberia and the Mediterranean rather than coming from Central Europe. In fact, the DNA shows that, in what might be termed the first invasion of Britain, these farmers eventually replaced most of the native hunter-gatherer population.

A series of invasions.

The first recorded attempt to conquer the island is, of course, the invasion by Julius Caesar in 55 BCE. His attempt at conquest might have failed but a strong trading relationship developed and a Roman presence remained on the island for five centuries. With the Roman departure in 410, various tribes from northern Europe – mainly Jutes, Angles, and Saxons took control of the island although there’s no evidence of any planned large-scale invasion.

Viking raids of the northern coast began in 793. What began as isolated and periodic raids turned into a full scale invasion when the Great Heathen Army landed in East Anglia in 866 and they had overrun all but the east of the country by the end of that century. By the early eleventh century, all of present day England would be united with the Danes and Norwegians under the rule of King Cnut the Great.

[Image from Wikimedia Commons – Public Domain.]

Cnut died in 1035 and was succeeded by his two sons Harold Harefoot and Harthacnut. They, in turn, were succeeded by the Anglo-Saxon King Edward the Confessor who ruled until the Battle of Hastings in October 1066. Then came the Norman invasion and the crowning of William the Conqueror in London in December of that year. (I recount some of this in a little more depth in my discussion of the Bayeux Tapestry.)

Military spats between Britain and Europe would continue for nearly another 1,000 years finally ending (for now) with the end of the Second World War on 8 May 1945. Great Britain appeared to cement its reunification with the continent when it joined the European Economic Community on 1 January 1973. Of course, that came to an end 47 years and one month later on 31 January 2020 when the island completed its most recent Brexit.

Next up on Todd’s Olympic tour, the host of the 2020 (2021?) Olympic games, Tokyo. See you there.

Came across this after a random search looking for a distraction. Very nice article. It was nice reading something interesting like this today.

I thought I would leave my first comment. I don’t know what to say except that I have enjoyed reading. Nice blog. I will keep visiting.

I don’t like your site design very much. The articles are great tho’.

You blend creativity with interesting content It’s truly commendable.