De Soto – the explorer not the car.

Some historians speculate that ego impelled Hernando de Soto to return to North America. De Soto amassed great wealth with Francisco Pizarro in conquering the Incas. On returning to Spain, he likely could have retired as a young man of means and leisure. However, he sought the title of marquis so he could claim status equal to his commander in Péru. Thus, De Soto cajoled King Carlos V to grant him “the right to explore and conquer La Florida.”

He arrived in Tampa Bay on 25 May 1539 where he led his crew of some 600 men and 220 horses ashore. After wintering near Tallahassee in the chiefdom of Appalachee, he entered what today is southern Georgia in early March 1540. Over the ensuing months, De Soto and his men explored what had been terra incognita – proceeding northeast into the present day Carolinas then turning west, crossing the Appalachians, and entering the Tennessee Valley east of what is now Newport, Tennessee.

[Image of De Soto from History.com.]

From there, they traveled southwest and reentered Georgia near the Little Egypt archaeological site before crossing into what is now Alabama in September 1540. While it’s likely that some of his encounters began and ended in skirmishes and some of De Soto’s typical behaviors – such as kidnapping tribal members to use as guides and holding Native American women and children hostage in exchange for supplies – generated generational hostility in relations between the native tribal people and the Europeans, it’s equally likely that none of these actions led directly to the collapse of the powerful chiefdoms he encountered even as he continued exploring the interior of the continent for another three years before dying of a fever in 1542.

However, much as Columbus had done half a century earlier, it is likely that De Soto’s encounters with Native Americans introduced European diseases such as smallpox for which the natives had no immunity. In this way, it’s probable that De Soto contributed indirectly to the fall of many of the tribal powers of the time.

Eventually Oglethorpe.

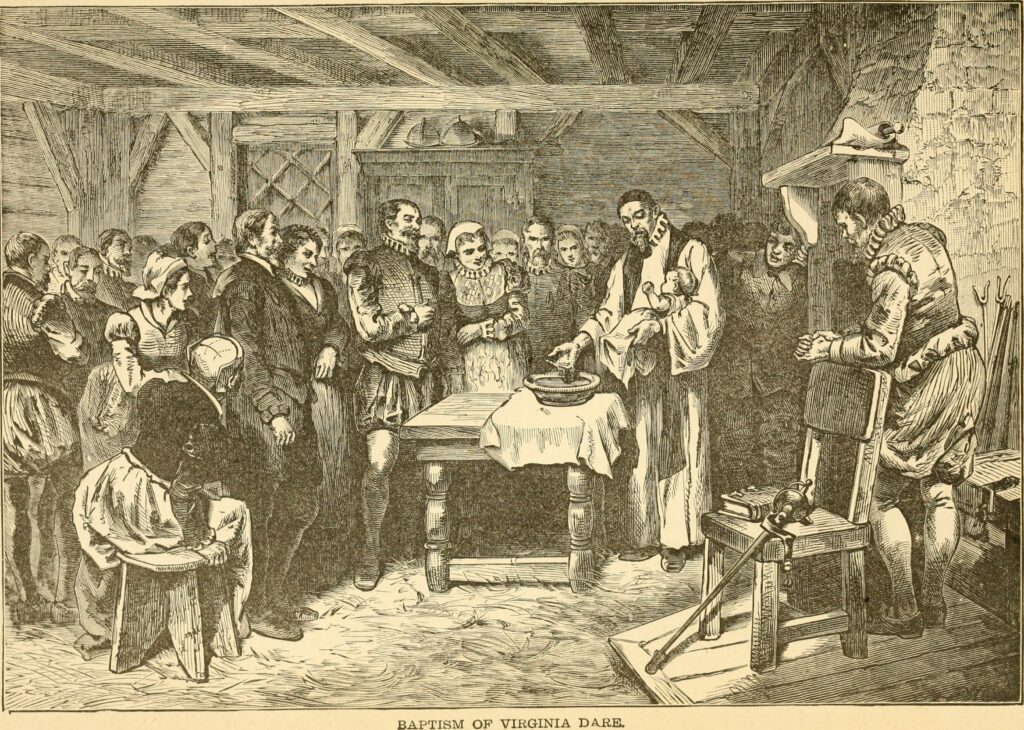

De Soto and the Spanish were more interested in spreading their empire to the west and the native tribes of the southeast were more or less undisturbed for much of the next century and a half. Although the first English settlement came only 45 years after de Soto’s death, and registered the first known birth of a person of European parents – Virginia Dare –

[Image from Wikimedia Commons – Public Domain.]

that colony on Roanoke Island off the coast of North Carolina vanished into the mists of history leaving but a few wisps and traces for archaeologists to unearth.

Meanwhile, the Spanish remained a forceful presence along both coasts of Florida while the English (Plymouth 1620) and Dutch (New Amsterdam 1624) were gradually settling the northeast and moving southward along the east coast of the continent. Still, the tribes of the southeast, primarily Cherokee and the tribes that would come to be called Creek, had little contact with Europeans and most of their conflicts were with one another. For example, after De Soto’s initial contact with the Cherokee in 1540, the next known contact between that tribe and any Spaniard occurred in 1566 with a small expedition sent out by Pedro Menendez from Fort San Felipe near present day Port Royal, SC.

By the late seventeenth century, the British and Spanish were vying for control of the Carolinas but those skirmishes remained mainly confined to a narrow area near the coast. The tribes farther west were not yet significantly impacted. On 12 February 1733 armed with a 1732 corporate grant “in trust for the poor” (e.g. indentured servants) from King George II, James Oglethorpe steered the ship Anne with the first 120 British settlers into what became the city of Savannah.

[Wikipedia – National Portrait Gallery – Public Domain.]

(From 1735 to 1750, Georgia was the only British colony that explicitly prohibited African slavery in its Charter likely because it received much of its labor from British Prisons. After overturning the ban in 1749, it took only a quarter of a century until the enslaved population outnumbered the colonists.)

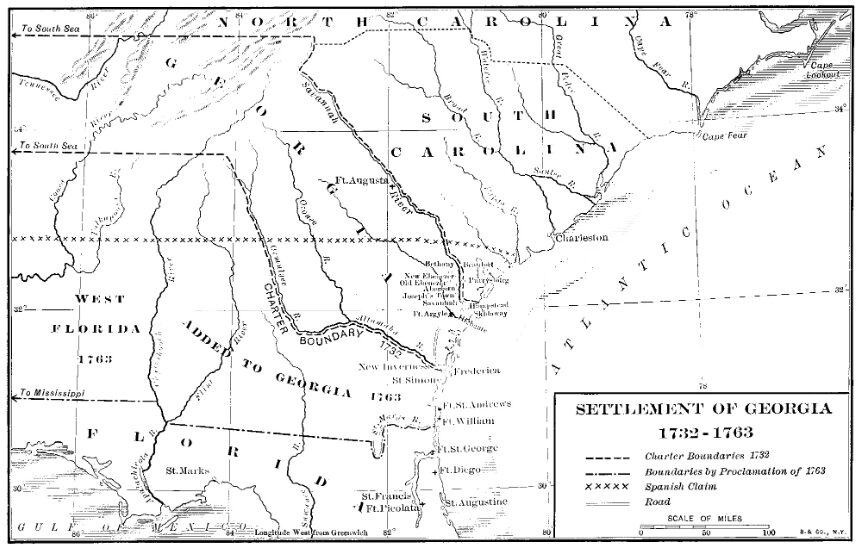

The 1748 Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle set Georgia’s original southern boundary at the Altamaha River. However, by the 1750s British settlers from South Carolina had pushed as far south as Cumberland Island near the St. Mary’s River thus squeezing the Georgians.

[Map from Wikipedia – Public Domain.]

To lose a Confederacy make it too loose.

For about a century there were no great battles between the native population and the Europeans likely because European diseases had so devastated tribal people living in the southeast – killing as many as ninety percent in the decades following the arrival of the Spanish – that the groups maintained a safe distance. By the early eighteenth century, the total native population had rebounded and likely approached 20,000.

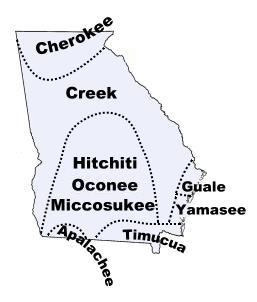

Although the great chiefdoms had long since disappeared, the tribal people of Georgia and Alabama had organized themselves into loose alliances of small villages speaking closely related languages. Often, when a town reached a population of 400-600, about half its residents relocated to a nearby site establishing a new town while maintaining ties to its mother village. This helped cement various alliances that stretched from the Ocmulgee River in Georgia to as far west as the Coosa in Alabama.

Initially, white settlers in Georgia called the Indians who lived in the Ocmulgee area Creeks in a form of shorthand for “Indians who live near the Achase Creek” but over time they applied the term to all Native Americans of the region including allied tribes such as Hitchiti, Oconee, and Guale.

Thus was born the Creek Nation.

By the time Oglethorpe arrived in 1733, the tribes of the Creek Nation had preexisting trade relationships with white settlers of South Carolina. The Creeks sold them captured Natives from Florida and deerskin. The former sales diminished in Georgia once the Charter changed to allow the sale of African slaves but in general, the tribes’ relationship with the settlers remained unchanged through and beyond the American Revolutionary War.

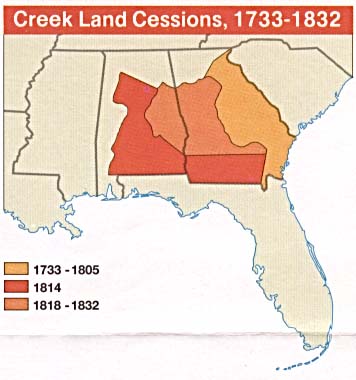

As the deer population decreased and trade diminished, the whites increasingly saw the Creek as impeding their expansionist plans. Eventually, under-armed Creeks ceded their lands east of the Ocmulgee River in the Treaties of New York (1790), Fort Wilkinson (1802), and Washington (1805). Their decentralized political system had inhibited their ability to act cohesively and they would ultimately suffer further from this lack of a centralized structure.

Because unaffiliated tribes had been artificially grouped together, it resulted in division within the Creeks themselves. Among the factors contributing to dividing the Creek Confederacy into two main factions known as the White Sticks and the Red Sticks were the declining economic situation among all the southeastern tribes, expanding white settlement along Creek borders and into Creek Territory, and the increasing accommodation of American demands by the Creek National Council.

The Creek War of 1813 began as a Civil War between those mainly Lower Creeks, who not only accommodated the Americans but often tried to assimilate their culture (White Sticks) and those from the Upper Towns who resisted (Red Sticks). The Red Sticks also sided with the British during the War of 1812.

In 1813, the Lower Creeks, led by William McIntosh (also known as Tustunnuggee Hutke or White Warrior) allied with the Americans who saw the conflict as an opportunity to eradicate Creek power in the region.

[Image from Wikimedia Commons – Public Domain.]

The final battle of the Creek War at Horseshoe Bend decimated both sides of the Creek Nation. General Andrew Jackson forced the surviving Creeks to sign the Treaty of Fort Jackson in 1814, ceding most of their ancestral homelands to the U S government.

While the darkest area on the map above represents the territory ceded in the Treaty of Fort Jackson, a look at the lands ceded between 1818 and 1832 shows that previous concessions did nothing to help the Tribes remain in their traditional homeland. In fact, under the Treaties of Indian Springs (1825) and Washington (1826) – the former also signed by McIntosh who was assassinated soon thereafter – the Creek were effectively detached from their homeland by 1827.

Neither Merle Haggard nor the Native Americans.

In 1969, Merle Haggard and the Strangers released one of the singer’s biggest hits – Okie From Muskogee. Haggard’s father was from Checotah, Oklahoma but Haggard was born in Oildale, California. The Muscogee tribe had been lumped in with the Creek Indians together with the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, and Seminole (the so-called Five Civilized Tribes). This group, totaling nearly 60,000 people, were forcibly relocated to Oklahoma under the Indian Removal Act of 1830 by way of the Trail of Tears. So, as the heading states, neither Haggard nor the First Nations Muscogee people have traditional ties to the place Haggard claimed and the place they now mainly reside.

(There is a tenuous connection between the Haggards and the Muscogee-Creek, however. Checotah was named for Samuel Checote who was the first chief of the Creek Nation elected after the American Civil War.)

In the next post, I’ll take you to London.