Inka-Dink-Khipu

Let’s start today’s post with a bit of a thought experiment and see if we can, if not upend, at least unbalance a conventional belief. Here’s the subject: For more than five centuries, based mainly on contemporary reporting, historical and archaeological thought has held that the Inkas had no writing system.

Think about the history of writing. By the time the Inka Empire arose in the 15th century, impressions in stone or on paper had existed in the Old World for millennia. The Greeks began using their alphabet in the eighth or ninth century BCE. Egyptian hieroglyphics predated the Greeks by thousands of years. Stone. Paper. Scribes. Tradition. In his 13th century travels along the Silk Road in Asia, Marco Polo would have encountered the logographic writing system of the Chinese and other types of script along his way.

Gutenberg began experimenting with his printing machine nearly a century before Pizarro arrived in Per├║ and had it in commercial use by 1450. By the middle third of the 16th century, books were relatively common in Europe so it makes sense that to Spanish eyes, since the Inkas had nothing comparable to paper or ink or even stone tablets they had no writing. But it’s not easy to run an empire without some sort of record keeping.

Because they would have been looking for what they knew, perhaps the Spaniards failed to fully recognize what they saw. For example, Jos├® de Acosta writing in the 16th century described something he called a “quipu” but what was, in reality, a yupana – an Inka counting device.

[Yupana photo from Wikipedia – Public Domain.]

He showed an incomplete understanding of its use writing in his book┬ĀHistoria Natural Moral de las Indias,

To see them use another type of quipu that employs grains of maize is a fascinating thing. For to make a very difficult calculation, to see how much each person must contribute, which an excellent accountant would have to do with pen and ink, these Indians, taking so many grains from that place and adding a certain number from this, and hesitating a hundred times, will take their grains and put one here, three there, and eight I donŌĆÖt know where; they will move one grain to another place, switch three from elsewhere, and their account comes out very accurately, without the slightest error; and they know much more clearly how to balance an account of what each one has to pay or give, than we could accomplish with pen and ink…

Keep thinking.

Next, consider the history of literacy in Europe. Under Roman rule literacy was common but after the fall of the Western Roman Empire in the late fifth century, the ability to read and write was limited to men of the church and some members of the nobility. Thus, while we can’t be certain, it’s no stretch to think that if the Inkas had any form of literacy they might have similarly confined it to the elite classes. Nor would it be outrageous to think that, as the Inkas saw the Spanish casually and thoughtlessly dismantling their shrines, temples, observatories, and their other indicators of intellectual life, that, as they saw the brutal treatment of their princes and priests, they might have kept silent as a means of preserving not only their knowledge but themselves. Perhaps through silence they sought to keep the Spanish from gaining further understanding of their world.

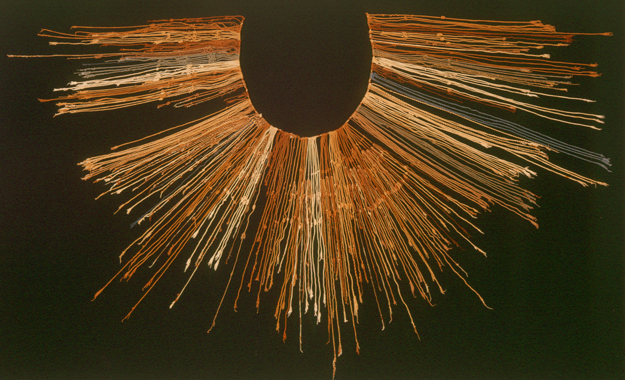

Finally, imagine yourself as a chaski – one of the runners charged with transmitting messages to the Sapa Inka. As a chaski, you know your importance but you also know that delivering an inaccurate message meant punishment that could go as far as execution. Under those circumstances, you might want to have a mnemonic aid that you could easily carry and hand to the next runner. Ladies and gentlemen, I present a real Khipu (quipu).

[Photo from Wikipedia By Pi3.124 – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0.]

Lost with no translation.

It’s clear from the photo above that a khipu isn’t a form of writing familiar to anyone (other than perhaps the Inkas). However, its purpose was more than decorative and every indicator points to it being more than a counting device like the yupana. Using knotted cords as a means of non-verbal communication isn’t particularly novel. In fact, it predates the Inkas by more than 2,000 years. Confucius, who lived from 551-479 BCE, wrote, “the men of antiquity used knotted cords to convey their orders; those who succeeded them substituted signs or figures for these cords.”

Even the records of the Spanish conquistadors provide evidence of the importance of the khipu to Inkan society. The Sapa Inka assigned a khipucamayoc or keeper of the knots to every community within the empire. The khipucamayoc was a statistician, historian, accountant, census taker, and administrator. He would have been responsible not only for keeping track of the population but also its agricultural production and the town’s weaponry and reporting the same to the Sapa Inka. Large communities could have as many as 30 khipucamayocs.

It wasnŌĆÖt long before the conquistadors noticed that some khipucamayocs remained loyal to their original rulers and that they regularly lied about the contents of a message. The Spaniards then punished the keeper of the knots and, acting on behalf of the Catholic Church that had deemed them ‘the work of Satan’, they would destroy the khipus themselves. It wouldn’t be too surprising to think that many khipucamayocs suddenly became illiterate and, after living long lives, took the secrets of the knots to their graves.

[Photo from Wikipedia By Claus Ableiter nur hochgeladen aus enWiki – CC BY-SA 3.0.]

Talking knots.

So, what could the Inkas communicate through khipus and how might they have worked? The first hints came in 1996 with the discovery in Italy of a 17th century Jesuit manuscript titled┬ĀHistoria et Rudimenta Linguae Piruanorum.┬ĀThis document not only has a fragment of a khipu but also explains how it encoded language. It asserts that it combined the system of knots with ideograms from Inkan art that together represented phonograms or logograms. (An ideogram is a symbol representing the idea of a thing with no indication of the sound used to say it. For example, ? and all its emoji relatives would be considered ideograms. A phonogram is a symbol that represents a vocal sound. Think of the letter ‘h’. A logogram is a written character representing a word or phrase such as the Japanese system of kanji.)

This lent some tantalizing support to a claim made in 1988 by J Alden Mason in his book The Ancient Civilizations of Peru that had all the khipus survived, they would have provided a complete historical record of the Inkan Empire.

Then in 2005, Science magazine published a new discovery that khipus do indeed carry non-numeric data. This included monthly accounts of sentences imposed by local judges, the progress of crops, census records, and weaponry – the very information the khipucamayoc would have maintained and reported.

As the photos above show, there could be great variation from one khipu to another whether in its form, the number and placement of the knots, the colors and lengths of the various strings, or the number strings themselves.┬ĀWhile some khipus might have only a half dozen cords, others contained as many as 2,000. Taken together the colors, the knots, and perhaps even the type of wool communicated information that the khipucamayocs and magistrates could interpret.

Gary Urton, a professor of anthropology at Harvard University, analyzed the complicated system of knots and colors and concluded that they represent a coded language similar to the binary code used by modern computers. According to Urton, khipus are built on a seven-bit binary code capable of conveying more than 1,500 separate bits of information.

Now, thinking back as far as some of the statues like this one

that we saw at Tiwanaku, the patterns on the belt and skirt become more intriguing. If the Jesuit manuscript authentically explains the encoding of language, these designs (or ideograms) might take on additional meaning.

Although historians and anthropologists are working diligently, the breadth of destruction imposed by the conquistadors and the lack of an Andean equivalent to the Rosetta Stone, make the task of deciphering the code of the Inkas a daunting one. If they can succeed, it could open a door to knowledge not only about the Inkas but also to more ancient Andean civilizations.

Now, for those too young to understand the reference in the title of today’s post, I give you Jimmy Durante and Harry James.

-

It’s just a shot away – Prizren

March 6, 2026 -

Some things looking better, baby – Getting into Kosovo

March 4, 2026 -

Here, where the sky is falling – Kuk├½s

March 2, 2026 -

That’s when we fall in line ’cause we got Berat

February 27, 2026 -

Walking on the big stuff – a climb to Tragjas

February 25, 2026