I am by nature a skeptic and my travels have, in some ways, increased my disinclination to facile credulity. Over time I’ve come to perceive that local guides understandably want tourists to see their country, their city, or even a single site in as positive a light as possible and thus skew their explanations and descriptions to accomplish that. I knew nothing about Moray (pronounced More-eye) so when we visited the site I was ready to accept at face value our guide’s explanation that it was a massive and ingenious Inkan agricultural laboratory.

After all, even before the trip I’d read about the brilliance of Inkan architects and builders and now I’d seen some of it first-hand. I’d seen their mastery of water usage. I’d seen how the ancient people at Tiwanaku had developed the agricultural method called suka qullu and I’d seen so much terraced agriculture since we entered the Andes that its sight had become prosaic.

Although the Inkas were known for conforming their buildings to the contours of the surrounding landscape, the circular shapes of Moray struck me as curious because that seemed to be a unnatural way to build a farm.

Still, the explanation he offered seemed not merely plausible but reasonable. That the Inkas and other cultures were already farming on terraces had become self-evident as we rode through the Andes. Thus, it came as little surprise to learn that within these circles there existed a controlled temperature gradient that created micro-climates. Each level, we were told, matched a different environment in Inkan territory and that there was a cumulative difference of 15 degrees Celsius from the top ring to the bottom one some 30 meters below it. (A little post-trip research verified this remarkable circumstance. The controlled temperature gradient was first noted by the Australian physicist John Earls sometime in the late 1970s and he hypothesized that Moray was a large agricultural laboratory. A few years earlier, Patricia Arroyo had put forth the suggestion that the site was used to acclimatize plants to new climatic environments.)

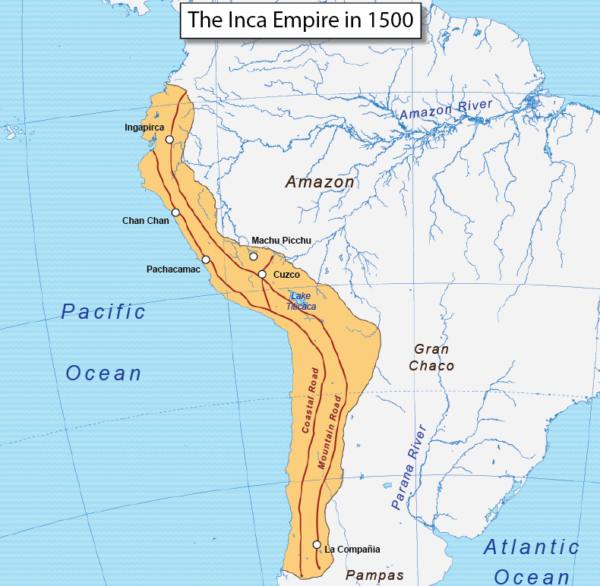

Both hypotheses have some credence. After all, as the map below reminds us, the empire stretched from the coast to the mountains, spanned thousands of kilometers and several climate zones all with growing seasons and soils specific to the local environment.

[From Quickworld’s Map of the Day.]

In a society without money and one that relied on a system of reciprocity, in a culture where a mere 40,000 people controlled a population exceeding 10,000,000, the introduction of new crops, better diet diversity, and more productive farming methods would be a demonstration of both benevolence and superiority.

(The reciprocity system of the Inkas was a sort of early form of socialism in which individual villages shared the production of whatever its ecosystem allowed – from crops to metals and gave any surpluses to other villages in different areas of the empire. In return, villages in less fertile areas might have supplied soldiers or labor crews that were building temples or roads. All people were required to provide some annual service to the empire.)

But then he said something almost in passing that made my ear hairs stand at attention. He talked about the site’s acoustics and how people standing 15 or 20 meters apart could hold a normal conversation. The equivalence he drew was that of scientists in a lab comparing notes. It may have been the case that this was either a fortunate coincidence or another remarkable aspect of the design and that Inkan agronomists indeed used it in just that manner. On the other hand, the convergence of a circular amphitheater shape with excellent acoustics raised the possibility of an alternative use and signaled the need for me to do more than transcribe and summarize his explanation. It demanded further research.

As it turns out, he may be right. But he may be wrong. It depends whose research you read and which writers you believe. Let’s take a look at the research and, if you want, a look at my photos.

In support of the agricultural lab theory.

The earliest assertion that Moray was some sort of agricultural site was, in fact, made in 1932 by the Shippee-Johnson archaeological expedition. (Robert Shippee was a Harvard-educated geologist and George R (Tuck) Johnson was a pioneer in aerial photography. Shippee had seen photos from Johnson’s aerial survey of Peru that inspired him to investigate the archaeological sites. The expedition was financed by Shippee’s friends and by both the American Geographical Society and the National Geographic Society.)

The photo above is of the largest and best preserved of three similar circles at Moray. The round bottom, 30 meters below the top started as a natural hollow that geologists call a doline formed by the constant erosion of karstic rocks. Six central terraces rise in concurrent circles above it. Each terrace is lined with low-lying aqueduct channels that irrigate them and the circular bottom is so well drained that it never completely floods. It’s not known whether this is the result of man-made tunneling beneath the ground or is due to geologic conditions.

Notice the six additional elliptical terraces connected to the main circle by the flat mezzanine and behind them to the right the eight partial terraces. The orientation of the levels with respect to the wind and the sun appears deliberately designed. Together, these 20 levels create the full 15-degree temperature variance with the warmest terraces at the bottom. This range of temperatures approximates the range of temperatures found across the empire.

(This photo is a smaller set of terraces at Moray possibly used for oats and other grains.)

Additionally, soil analysis indicates that the soil on different levels had been brought from different areas. (This statement came from a single source and in my limited reading I could neither confirm it nor find any sources that matched the soil to any specific place. The presence of non-native soil has a simple and plausible alternative explanation. The Inkas knew that a certain crop – say potatoes – grew better in soil that wasn’t native to the local area and, much like the street arabbers of my Baltimore youth who carted and sold fruit, vegetables, fish, and yes, topsoil, they simply imported better soil.)

Finally, there’s the question of variety. Today, between 3,800 and 4,000 varieties of potatoes are grown in PerĂş. Of those, at least 3,000 were known at the time of the Inkas. Similarly, about 35 types of the 55 known varieties of corn were being grown in the 15th century. This biodiversity clearly was not accidental particularly given the difficulty in domesticating corn and the fact that, before they were domesticated, wild potatoes had varying levels of toxicity. These factors appear to make agricultural experimentation not merely a curiosity but a survival tool.

And finally, there is the name – Moray. The Quechua word for harvest is ‘almuray’. Its linguistic kinship with the current name is easily seen.

In the next post, we’ll take a look at a plausible alternative.