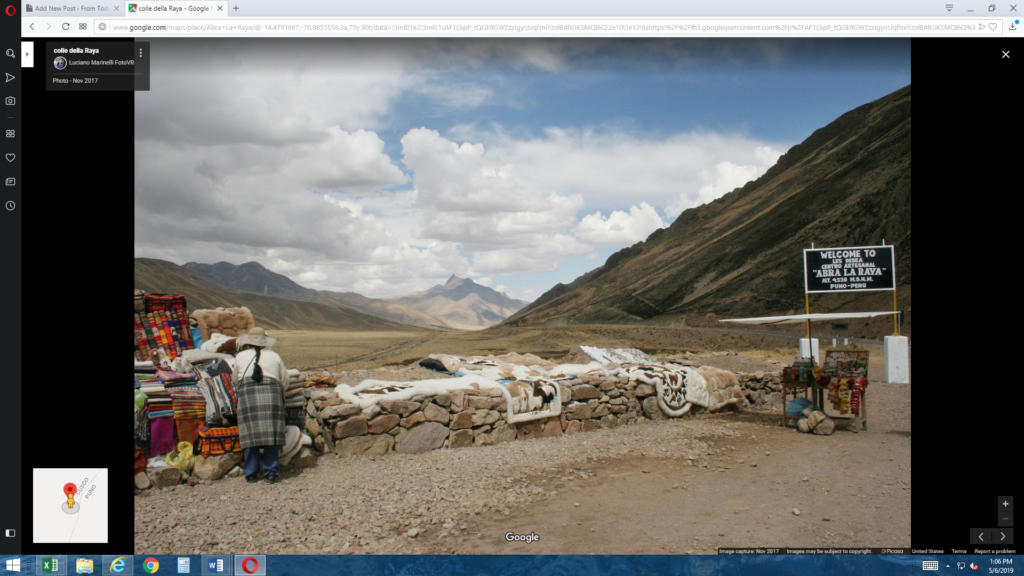

Today we’re setting out for another day long bus ride. This one will take us from Puno to Cusco. Along the way we will pass through Pukara and Abra La Raya. While our bus didn’t stop there, it is Abra La Raya that quite literally provides the title for this post. Here’s a screenshot from Google Maps.

If you enlarge it, you will see the sign places us at the altitude of 4,338 meters above sea level (MASL) which is, in fact, the physical acme of our trip. By the time we reach Cusco we will be a mere 3,400 MASL.

(Actually, the remainder of the trip isn’t exclusively at progressively lower altitudes. We’ll descend from Cusco to Ollantaytambo and thence to Aguas Calientes. From there we have a day trip ascent to Machu Picchu and a return to the higher altitude of Cusco before Jill departs for the Amazon and Jan and I go on to Lima, but the pass at La Raya is our physical apex. The alternate title of the post is a small Rocky & Bullwinkle tribute.)

Pukara or as the Spanish write it Pucará.

We are now entering the part of Perú where, by necessity, the coming posts will be principally about the Inkas so it might seem a bit odd for me to opine that this is a rather Eurocentric view of the country and the Andes. Yet, in some ways, it is. If you read the post about Tiwanaku, you might recall that it began with this thought,

…concurrent with Tiwanaku there was Moche, Huari, and Nazca. And before all of them there was Chavín. Before Chavín was the Caral-Supe.

These are only a few of the pre-Columbian cultures of the Andes and yet most of our knowledge and most of the pixels in this blog will center on the Inkas mainly because they were the dominant empire when the Spanish arrived in full force in 1532. As I will note (probably more than once), from its rise in 1438, the Inka Empire lasted barely more than a century if you want to consider the very last remnants conquered by Spain in 1572 as part of the empire’s lifespan. But Francisco Pizarro conquered Cusco – the center of both the Inkan Empire and its spirit – by 1533. For all intents and purposes, this brought an end to Inkan rule over the vast territory they called Tawantinsuyu that’s commonly translated as the Land of the Four Corners but which could also mean One Land Four Nations (tawa means four and suyu indicates nation).

A bit more than 100 kilometers north of Puno is the archaeological site of Puka Pukará

[Image of Puka Pukará from Evolution Treks Peru.]

where the earliest archaeological remains have been dated to 1,800 BCE in the Chiripa period. This particular group’s rise coincided with the development of distinct styles of ceramics, pottery, and textiles that archaeologists have deemed them representative of Pukará culture. Evidence points to this being the dominant culture of the Titikaka region perhaps as early as 850 BCE and that its decline began with the rise of Tiwanaku sometime in the second or third century BCE.

Although this society predates the Inka by more than 1,000 years and lasted centuries longer, it was effectively extinct long before the arrival of the Europeans so they took no note of it and we did no more than pass it on our way.

However, we also passed this super-sized example of a Pucará Toro or Pucara Bull.

More typically one might see a smaller pair of Toritos de Pucará on the roof of someone’s house.

[From blog.casa-andina.]

Because they are a curious blend of symbols from the native polytheistic religions and Catholicism, the Pucará bulls have achieved some international renown. Two bulls with bulging eyes, extended tongues, and what are clearly Andean symbols (such as the spiral found carved into ancient stone monuments) typically flank a cross. In addition to being considered an expression of Andean identity, the toritos are intended to bring happiness, protection, and fertility to the residents. But since the bull isn’t native to the Andes, one might reasonably wonder why this animal and not, say, a llama. And why the cross?

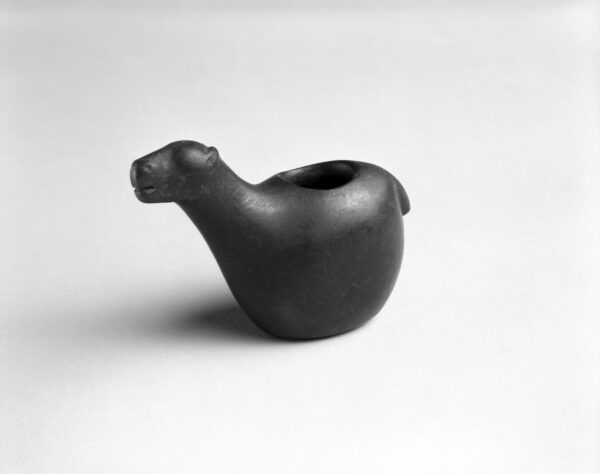

The answer begins in the pre-Columbian history of the region. For these ancient people, their domestic animals – mainly llamas and alpacas – had a protective spirit called an illas or a mulla in Aymara and an enqa in Quechua. To protect the animals and increase their production they created a stone miniature representing that spirit which they then buried.

[Image of 16th century llama effigy BY Brooklyn Museum, 36.683_bw.jpg.]

The process of burying the effigy amulet was also considered an offering to Pachamama asking for a bountiful harvest.

Perhaps because there was often a degree of similarity with their own beliefs, (the presence of Viracocha and Pachamama, for example) the Inkas were generally content to allow the cultures they integrated into their empire – whether by force or negotiation – to retain their local religions. The Spanish arrived in the 16th century and had a different set of ideas and, at the time, the Inkas were weakened by numerous internal conflicts that the Spanish exploited on the road to conquest.

At least some of the people the Spanish “conquered” considered themselves liberated and settled into a new life with little conflict. Throughout the process of conquest, the Spanish brought smallpox and horses. They also brought cattle and Catholicism.

One origin story of the adoption of the bull into local mysticism asserts that when the Spaniards arrived in the region of Pucará they interrupted some sort of festival in a place called Chepa Pupuja. The people took possession of one of the Spanish bulls, painted it, and blew pepper up its nose. The bull reacted as one might expect. Those who were present and saw the enraged bull remembered it and this became the expression we still see on Pucará bulls today.

[Photo from notesfromcamelidcountry.]

The artisans in the nearby community of Chepa Pupuja were renowned for their ceramics and they began to reproduce an image of the bull that they had either seen or had described to them. Cattle quickly became useful and the farmers now had a new animal they adopted into their ancient fertility, happiness, and protection rituals. Because they transported and sold their work in Pucará, the source of the bulls was attributed to that city and not to Chepa Pupuja.

Of course, the Spaniards wanted to convert the conquered natives to Catholicism and, while it might seem odd to say this, adopting this new religion wasn’t a particularly prodigious conceptual leap for the local population. Recall that three realms comprised the prevailing spirituality – Hanan Pacha, Ukhu Pacha, and Kay Pachca. In the minds of the conquered Inkas and their subjects, these analogized relatively easily to the Catholic concepts of heaven, hell, and earth. In a similar way they connected the Virgin Mary with Pachamama.

Traditional Andean culture is experiencing something of a 21st century revival. And it is a culture as steeped in symbolism as the coca tea leaves that soothe life at altitude. Blending symbols from two religious traditions fit together like the flawless stonework of their Inkan ancestors. The cross is the Spanish Illa and the bull a newfound Inka illa.

Note: In keeping with my 2022-2023 reformation of the blog into shorter entries, backdated to maintain their sequence, any comments on this post might pertain to its new configuration. See the full explanation in the post Conventions and Conversions.

You are so much fun to read! As always, thanks for sharing.

Thanks for both the comment and the compliment, Jennifer. (If anyone wonders why I ask for comments, each month I mark spam day. This is the day on which the number of monthly spam comments exceeds the total comments on my posts since the site’s inception.This month it was Monday the 20th.)