Without stopping, the drive from Sundance to Douglas through Cheyenne to Laramie crosses about 360 miles and requires five and a half hours more or less. The stops I recounted in the previous posts added minimally to the distance but considerably to the time. It was well past 15:00 when I arrived at the motel so, though I felt a bit like I arrived on an older mode of transportation like this,

I hadn’t. I was at peace with my late afternoon arrival because, honestly, Laramie isn’t brimming with tourist attractions. Even looking through my “usual suspects” web sites offered few options beyond some of the sites I’d seen en route. Roadside America suggested the “Big Brown Copper T-Rex” on the University of Wyoming campus and a statue of Chief Wakashie located somewhere in the Historic District. Atlas Obscura had nothing to add and even Trip Advisor merely added some mansion – the name of which I can’t recall – and something called the Mural Project.

I could have driven a couple hours south to the Medicine Bow National Forest or stopped near Lincoln’s head to climb the Vedauwoo rocks but I suspect you know me well enough by now to deduce that I was disinclined to do either. Instead, I went to the Wyoming Territorial Prison as suggested by R A.

From prison to farm.

If you recall how quickly lawlessness came to Deadwood, it should come as no surprise that the situation throughout Wyoming was only marginally better. Wyoming officially became an incorporated territory of the United States in 1868 and theft, forgery, bank and train robberies, murder, and cattle rustling persistently plagued the area. Building a territorial prison became a pressing need.

The site selected was just outside Laramie and the original prison, built to house 84 prisoners opened its doors in 1872. Early in its history, the prison charged the territory $1 per day to house, clothe, and feed the convicts. Since this was more than it cost the territory to ship prisoners out of state, from 1873 to 1877, the facility rarely housed more than 10 prisoners at any one time.

By the last third of the decade, the situation changed dramatically. It survived its first fire and 11 escapes and became severely overcrowded leading to the construction of a second wing – largely with prison labor – that opened in 1889.

The building in the photo below has been restored to look as it did in 1895 because it’s from that year that the best photographic evidence exists for the similarly restored interior space.

The original cellblock is the light colored structure on the right. Also visible are the 12 foot high wooden fence that enclosed the prison and the transport wagon that brought the earliest convicts from Laramie where they’d been processed initially.

Prisoners sent to the territorial prison served their sentences under a strict Auburn Prison System. Entering the jail, they received a card explaining the rules. Convicts were required to be silent at all times, participate in prison work gangs, leave their cells only on command, and move about the prison in lock step. When going to work and other activities they wore black and white striped uniforms and had their names replaced by numbers. (I don’t know if anyone bore the number 2-4-6-0-1.) Since many of the convicts were illiterate, they learned the rules only after being punished for violating them.

Some of the easier punishments included loss of tobacco and library privileges, solitary confinement in the “dark cell,” and a bread and water restricted diet. Repeat offenders were forced to carry a ball and chain or have a device strapped to their shoes that often resulted in torn ligaments.

The federal government managed the prison until 1890 – the year Wyoming became a state. At that point, management transferred to the state government which ran it until 1903 when prisoners were transferred to a new prison in Rawlins 100 miles to the west. The state built the new prison in Rawlins partly due to the poor reputation of the Laramie site and partly because they didn’t want one city to hold all the major state funded institutions. Cheyenne became the capital, the prison moved to Rawlins and the “lunatic asylum” settled in Evanston. Laramie retained the University of Wyoming which was established in 1886.

Over the years, to offset the costs of prison maintenance and, to a lesser degree, provide inmates with some occupational training, different wardens tried to build revenue-yielding industries. The work included cutting trees, growing potatoes, cutting ice blocks, making bricks, quarrying stone, and making hand carved furniture.

However, the prison’s greatest commercial success was broom production. Constructed in 1892 by inmates, the broom factory was a hub of activity. By 1900, it was producing 720 brooms per day. Carefully labeled with the name of a local retailer to hide the place of manufacture, brooms were delivered to towns in Wyoming, Nebraska, California, Utah, Montana, South Dakota, Colorado, and Idaho. Some were shipped to Japan and Hong Kong. It was also used for several escape attempts and set ablaze more than once.

After the prison moved to Rawlins, the state ceded the Laramie facility and its grounds to the university that then used the site for 86 years to conduct agricultural experiments focusing mainly on livestock breeding before returning it to the state. It opened to the public as a historical site in 1991. (Although our guide described the livestock section as particularly interesting I only had time to breeze through it after our abbreviated tour that began close to the museum’s closing time.)

The Territorial Prison housed a total of 1,063 convicts, including recidivists, in the 30 years from receiving its first prisoner in 1873 until it closed in 1903. Thirteen of the prisoners were women though only 12 individual women served time there. One, whose name was inaudible on my recording of the guided tour, was a repeat offender.

Raindrops keep fallin’ on my head.

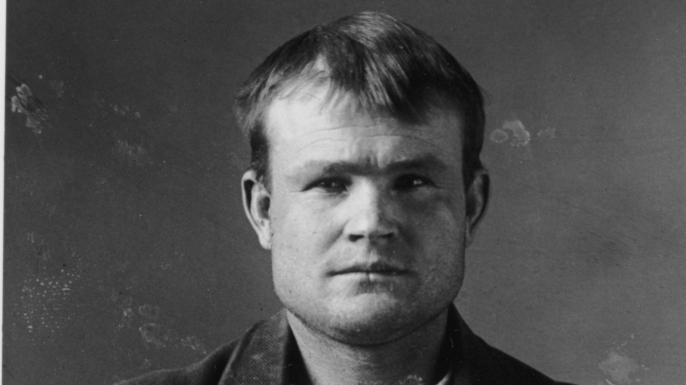

The most famous (or infamous) convict housed at the Wyoming Territorial Prison was one Robert Leroy Parker better known as Butch Cassidy.

[Photo of Butch Cassidy from history.com].

In fact, this was the only prison in which Parker (AKA Cassidy) ever served time.

Born 13 April 1866 in Beaver, Utah, he was the eldest of 13 children. His Mormon parents and grandparents had moved from England to Utah in response to Brigham Young’s call for settlers to come to the Beehive State.

By age 16, Parker had left home and, while working at a Utah ranch, met a cowhand and small-time cattle rustler and horse thief named Mike Cassidy. The elder Cassidy is said to have taught him how to train horses and shoot a gun. After getting into trouble with the law, Mike Cassidy fled the area. Parker also departed Utah in search of new opportunities after turning 18 in 1884.

Working in the mining town of Telluride, Colorado, Parker and several companions, who would eventually become known as the Wild Bunch, pulled off their first bank robbery on 24 June 1889 absconding with more than $20,000 from the San Miguel Valley Bank. Not long afterward, Parker started using the surname Cassidy, in honor of his former mentor and began calling himself Roy Cassidy. According to the legend, he eventually moved on to Rock Springs, Wyoming, where he landed a job in a butcher’s shop and there became known as Butcher Cassidy, which then morphed into Butch Cassidy.

For a man who became adept at robbing banks and trains (he apparently had his first successful train robbery in 1890) a surprisingly minor crime landed Cassidy in the Territorial Prison. In 1894, a cattleman accused him of stealing a horse worth five dollars. Cassidy claimed he’d bought the horse but couldn’t produce a bill of sale. He was sentenced to two years.

Ever a charming fellow, Cassidy was soon working in the kitchen – one of the prison’s plum jobs. (It was warm through the long, cold Wyoming winter and likely afforded the opportunity to sneak some extra food and had access to the farm in the back.)

Affable, personable, and apparently industrious, he was released six months early for good behavior.

When he was released, Cassidy allegedly promised Wyoming’s governor that he’d leave the territory’s ranchers alone, so he and his fellow bandits naturally turned to robbing banks and trains. Cassidy’s robberies were always well planned and usually had supplies and extra horses stashed along the intended getaway route. Although he became notorious for pulling off holdups throughout the West in the 1890’s, he was never known to employ excessive gun violence. In fact, when he wasn’t committing crimes, Cassidy was considered friendly and had a reputation for being helpful to his neighbors and generous to people who’d given him refuge.

After a look at the towns and jails that held Harry Longabaugh and Robert Leroy Parker aka the Sundance Kid and Butch Cassidy, we’ll next delve into the case of Matthew Shepard.