Those of you who have followed my travels through these journals know that I try not only to share my personal experiences but also that I try to enrich those experiences by including geology, geography, history, or any discipline I think adds value, perhaps bringing a new perspective because, to me, if you don’t learn something and widen your world view there’s not much point to leaving home.

You may or may not be aware that I’ve often done extensive research long before I embark on any of my adventures but, as I gather additional facts and perspectives along the way, I continue that research for some time after I return. As I began the drive from Billings to Little Bighorn, my thoughts turned to my pre-trip reading about the battle there and I pondered, as I had before I left, the challenge of distilling not only the events of 25 June 1876 but the decades of broken treaties and various battles that preceded it into a manageable length and format. I found it as daunting then as I do now beginning the actual composition.

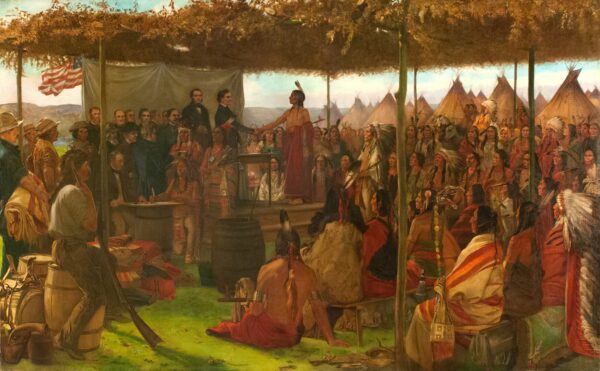

[Treaty of Traverse des Sioux from Wikipedia By Minnesota Historical Society – https://www.flickr.com/photos/minnesotalocalhistory/50889538307/, CC BY-SA 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=99401502].

Finding balance in this instance is difficult. Many books have been written about the Great Sioux Wars that had their pivotal point at the Battle of Little Bighorn and those books bring in many different perspectives and sometimes reach opposing conclusions. Equally confounding, the accounts of the press at the time and the accounts that found their way into most history books present a very different story from both the contemporary Native American narratives and those passed down through their oral tradition.

Westward Expansion.

The 20-minute film shown in the Visitor Center at the battlefield begins its narration with the Treaty of 1868 signed at Fort Laramie. From one perspective this is an appropriate place to start because one can draw a fairly straight line from the terms of this treaty to the battle on 25 June. However, by choosing this as a starting point, it neglects to inform the viewers of the unilateral violations of earlier treaties – particularly the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851 – by the American government that led to near perpetual battles and skirmishes between the Plains Indians and a voraciously land hungry expanding European American population. Although the troubles predate 1851, that seems to me something of a pivotal year so I will begin then.

Throughout much of American history, the Europeans who had colonized the east coast of North America looked for opportunities in the west and by the mid-1840s this expansion began accelerating. (The LDS exodus from Nauvoo, IL led by Brigham Young began in 1846 for example.) Supported by their government, most of these settlers were at best indifferent not only to the traditions of the native people who had dwelled in these lands for thousands of years but also to the treaty rights negotiated by the federal Government and those First Peoples. In many instances, they were dismissive of both. (Okay, I admit it, I like the Canadian term and will use it interchangeably with Native American and Indian.)

The Treaties of Traverse des Sioux and Mendota.

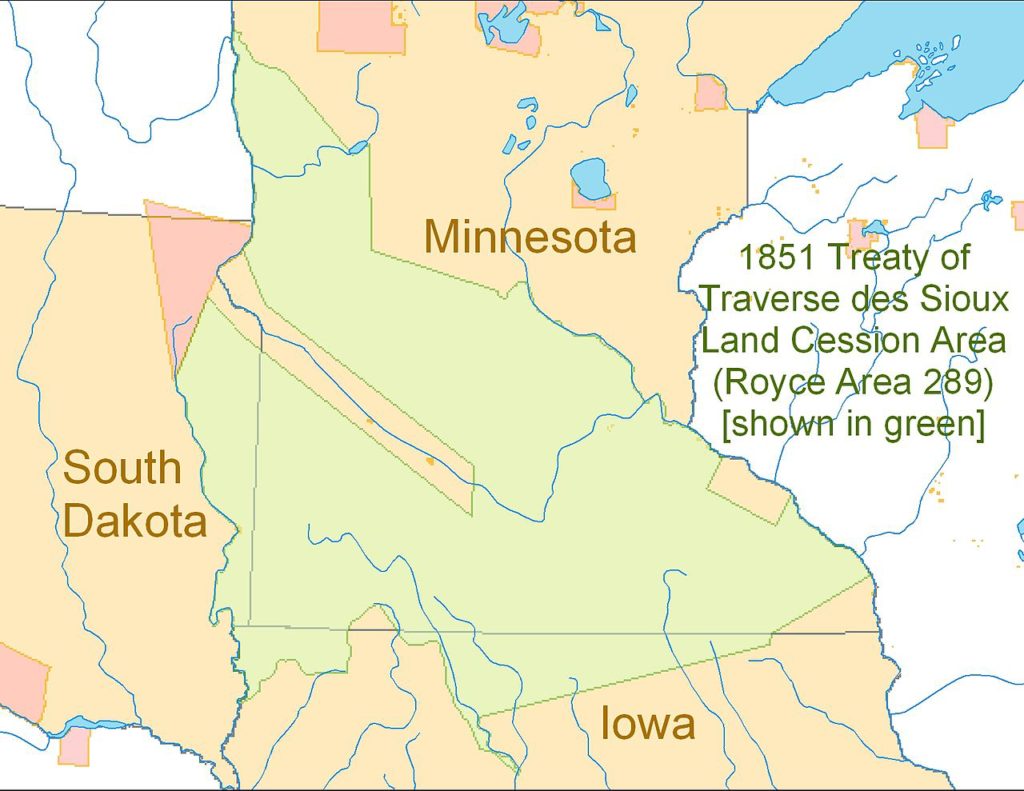

Among the first of the 1851 treaties was the Treaty of Traverse des Sioux signed on 23 July 1851. It was followed in short order by the Treaty of Mendota on 5 August. In these treaties, the Sioux ceded more than 24,000,000 acres mainly in present day Minnesota as shown in this map from Wikipedia.

[Map By CJLippert at English Wikipedia, CC BY 3.0].

The roots of this massive concession of territory can likely be traced to the First Treaty of Prairie Du Chien in 1825 and the Sioux defeat in the Black Hawk War fought in August 1832.

In the 1851 treaty, the government promised to pay the Sioux an annuity of more than $1,400,000 based on a rate of three cents per acre but with the U S government retaining $1,100,000 “in trust.” The government then turned around and sold the land to settlers for $1.25 per acre. Additionally, deliberately inaccurate translations of side documents known as “traders papers” transferred more than a quarter of the promised payments to traders, many of whom were utterly unscrupulous, who claimed it in settlement of alleged debts.

Now notice the narrow strip of unceded land straddling the Minnesota River which the government intended to be two reservations each about 20 miles wide and 70 miles long for the Wahpeton and Sisseton bands of the Upper Dakota Sioux. This land moved the tribes from their traditional woodland habitat to one that was mostly prairie. As more settlers moved into the area, the government then declared that these reservations (or Agencies, using the terminology of the time) were intended to be temporary and by 1858 the Sioux, facing a forced change in lifestyle and economic stress from receiving less money than the government had promised, conceded the territory on the north side of the river. These stresses combined with internal tensions between tribes unaccustomed to living together but now forced to share ever shrinking territory led to the Dakota War of 1862.

The 1851 Treaty of Fort Laramie.

Although complaints of stress between the European migrants moving west and the various Native American tribes of the plains had been growing since the middle of the 1840s, clashes between the tribes themselves and the ever-increasing number of westward migrants began to spike in 1848. Not coincidentally, this spike in migration occurred soon after the discovery of gold by James Marshall at Sutter’s Mill in Coloma, California on 24 January 1848 that spurred the California gold rush.

In 1850, former U S Superintendent of Indian Affairs Thomas Harvey began lobbying for a general council to negotiate the rights of passage through Indian lands stating that “a trifling compensation for this right of way would secure their friendship.”

The council, headed by David Mitchell, superintendent of Indian Affairs at Saint Louis,

[Portrait of David Mitchell from Wikipedia – Public Domain.]

opened on 8 September 1851 attended by U S treaty commissioners, representatives of the Arikara, Arapaho, Assiniboine, Cheyenne, Crow, Hidatsa, Mandan, and Sioux as well as, in a quasi-official capacity, Father Pierre-Jean De Smet and Jim Bridger. (We met the latter on my travels through Utah.)

Prior to convening the council, Mitchell had sent messages assuring various tribal leaders that the government would, “divide and subdivide the country for the permanent good of the Indians” and that the agreement would end “the bloody wars which have raged from time immemorial.” (The final treaty set forth traditional territorial claims of the tribes as among themselves leaving open the possibility of wars between the tribes.)

After smoking the peace pipe at the opening of the council, Mitchell declared, “We do not want your land, horses, robes, nor anything you have; but we come to advise with you, and to make a treaty with you for your own good.” He would later stress that these divisions of land would allow “the Great Father” to punish the guilty for any future depredations while again promising that there was no intent “to take any of your lands away…or to destroy your rights to hunt, or fish, or pass over the country, as heretofore.”

As we’ll see, Mitchell’s statement was simply not true.