I picked the wrong night to stay at the Hotel Blackfoot a few kilometers south of Calgary’s town center. There wasn’t a problem with my room, the meal, or any of the service. It was the wrong night simply because I happened to stay there on Monday. You see, on Thursday nights in (as the hotel’s website describes it) “the Hotel Blackfoot’s trendy Lobby Lounge”, they have regularly scheduled live jazz. There’s no jazz on Mondays.

But if live jazz doesn’t suit your entertainment needs, you can “Drop by on Thursdays, Fridays & Saturdays for sidesplitting laughs at Calgary’s premier live standup comedy venue” The Laugh Shop which offers an optional dinner buffet on Friday and Saturday.

The one name on the schedule I immediately recognized was Tom Arnold who’s performing there on 20-21 October. (I can’t attend because I’ll be in Spain but tickets do seem to be available for those who want to make the trip.)

Perhaps it’s just as well because, facing a long drive ahead before I reached my stopping point in Billings, Montana, I planned an early start Tuesday.

Big Rock Okotoks.

My first stop of the day will be in Okotoks about 20 kilometers south of Calgary’s city limits. (The site I’m visiting is actually about 45 kilometers from the hotel. Keep in mind that while its population is a bit more than one and a quarter million, Calgary is a sprawling metropolis covering more than 825 square kilometers. For comparison, Toronto, with more than double Calgary’s population has an area of about 630 square kilometers.)

When I described glacial erosion in Banff, NP, I wrote, “As glaciers advance and retreat, they can grind down mountains, scatter strange rock formations across the countryside and reduce solid rock to fine dust.” These ‘strange rock formations’ are properly called glacial erratics and they form when dislodged rocks are treated to what one might think of as a glacial piggyback ride. The rock is sitting on top of the glacier just going with the flow and enjoying the ride. But sometimes the ice melts unexpectedly quickly. When that happens, it deposits the now far-flung rocks in places they don’t belong leaving them as strangers in a strange land with no way to return to their place of origin.

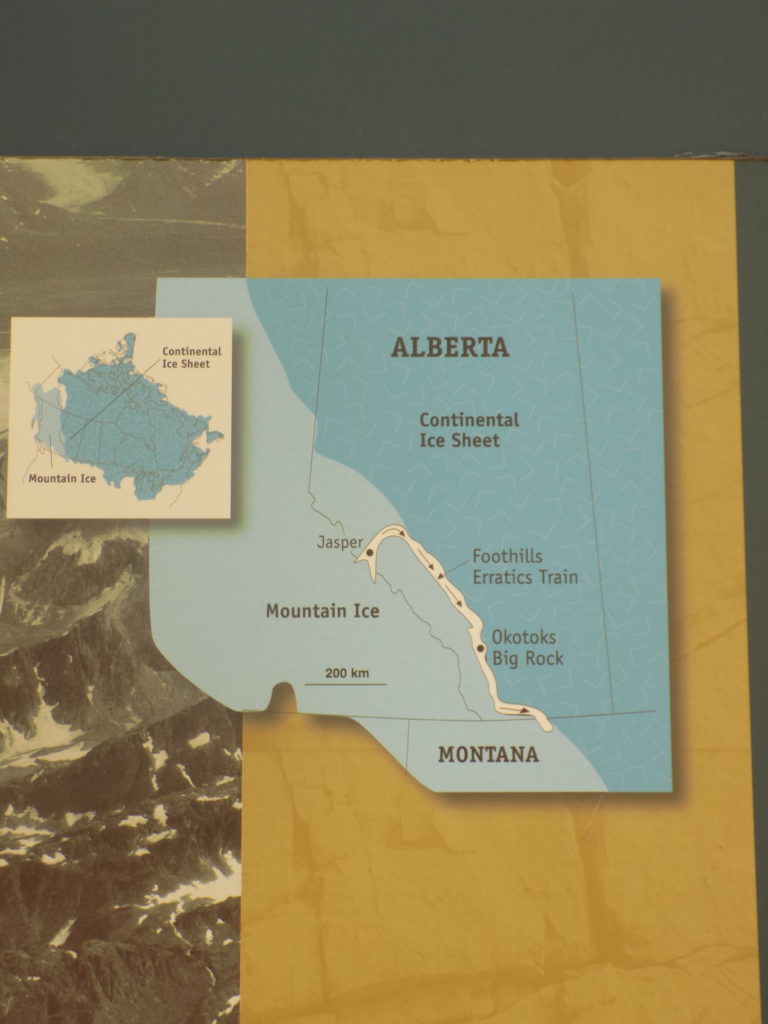

As it turns out, one of the world’s most extensive scatterings of glacial erratics lies along a one-kilometer-wide path that stretches for approximately 980 kilometers in Alberta, Canada. This north to south scattering of these abandoned migrant rocks, extending from Jasper National Park to Northern Montana is known as the Foothills Erratics Train (although you have to think of this train as derailed). If that southernmost point is the train’s engine, the Okotoks (pronounced OH-kuh-TOHks) Big Rock erratic considered by most to be the luxury carriage car of this train, is about one fourth of the distance between that engine and the caboose in Jasper.

Here’s how geologists tell the story of the Big Rock. It begins with layers of sediment comprised of sand, silt, and small pebbles deposited between 600 and 520 million years ago in a shallow sea. As time passed, the sediment built up layer upon layer as part of what geologists call the Gog Formation. While much of the sediment (and thus much of the composition of the Rockies) is limestone, in some places the heat and pressure generated by the weight of the overlying sediments compacted the sand grains compressing them into an extremely hard, durable rock called quartzite.

Big Rock was originally part of a mountain in what is now Jasper National Park 400 kilometers or more to the north. Sometime between 30,000 and 10,000 years ago, a large rockslide crashed debris onto the surface of a glacier that occupied the present-day Athabasca River valley. This debris, including Big Rock, was then carried out of the mountains on the surface of the glacier. The valley glacier slowly moved eastward to the mountain front, where, confined by the Cordilleran ice sheet to its west, it collided with the other huge continental ice mass known as the Laurentide ice sheet on its east. The valley glacier was deflected to the southeast, parallel to the mountain front and, as the ice melted, it deposited this atypical linear string of erratics.

The notion of the erratics receiving a piggyback ride is important because being on top of the glacier allowed them to retain much of their bulk and shape. Alternatively, had the rocks been transported by ice at the bottom of the glacier, by water, or by ice-rafting they would have a much different appearance. They would have been either quickly broken up into much smaller fragments, significantly rounded, widely dispersed over the landscape, or some combination of these.

Comprised of 16,500 tons of quartzite, the Big Rock, is the largest known glacial erratic on the planet. It’s nearly nine meters high, 41 meters long, and 18 meters wide. Because the area’s native rocks are largely sandstone, the quartzite composition of the rock identifies it as an alien.

The Big Rock is known not only for its great size but also for the large split down the middle. Naturally, the mysterious appearance of a gigantic, apparently misplaced rock in the middle of the prairie with a great split down its middle, has inspired a number of legends. One of them, a cautionary tale against taking back what you have given away, with its source from the Blackfoot tradition, describes how the split happened:.

One hot summer day, Napi, the supernatural trickster of Blackfoot peoples, rested on the rock because the day was warm and he was tired. He spread his robe on the rock, telling the rock to keep the robe in return for letting him rest there. Suddenly, the weather changed and Napi became cold as the wind whistled and the rain fell. Napi asked the rock to return his robe, but the rock refused. Napi got mad and just took the clothing. As he strolled away, he heard a loud noise and turning, he saw the rock was rolling after him. Napi ran for his life. The deer, the bison and the pronghorn were Napi’s friends, and they tried to stop the rock by running in front of it. The rock rolled over them. Napi’s last chance was to call on the bats for help. Fortunately, they did better than their hoofed neighbours, and by diving at the rock and colliding with it, one of them finally hit the rock just right and it broke into two pieces.

This site is of great spiritual significance to the Blackfoot people, and the name of the town and the rock are derived from the Blackfoot word for rock, “okatok.”

Note: In keeping with my 2022-2023 reformation of the blog into shorter entries, backdated to maintain their sequence, any comments on this post might pertain to its new configuration. See the full explanation in the post Conventions and Conversions.

Love the insight into Vulcan, Canada. Seems like a great place to be a Star Trek Nerd (admitting I am one – and value Star Trek much more than Star Wars, but that is a discussion best for a glass of wine or 3).

Cheers,

C