Picking up where I left off

It’s still yesterday (in blog time, of course).

As I noted at the end of the previous post, I’d finished walking chronologically backward and reached the beginning of the Trail of Time but still had barely covered a third of the distance to Hermit’s Rest at the western end of the South Rim Trail. Exactly how many of the six or seven miles I’d actually walk was still an open question. Still, it was time to get started.

The first vista after Maricopa Point and the end of the Trail of Time is Powell Point. Not only does this lookout have a monument to John Powell but it also provided some of the grander views the day afforded me – including this one.

Some words about John Wesley (not Boog) Powell.

As I noted in the previous post, John Wesley Powell led the first recorded expedition of white men through the entirety of the Grand Canyon. Of this we can be certain. If any record exists of any Native Americans making this journey it is, as of now, lost to history thereby making that journey the equivalent of the proverbial fallen forest tree. Thus, practically speaking, Powell’s expedition earns the title of being first.

In 1860, Powell enlisted with the 20th Illinois volunteers and initially served as a second lieutenant. He was quickly promoted to captain and, while commanding battery F of the Second Illinois Artillery, lost his right arm at Pittsburg Landing during the battle of Shiloh. As a healed, one-armed man, he returned to the service and fought in the battles of Champion Hill and Black River Bridge. After a second surgery on his arm, he again returned to his post and eventually earned the title of major and chief of artillery, first, of the 17th Army Corps and subsequently, of the Department of Tennessee, taking part in operations before the Atlanta Campaign and in the battle of Franklin near Nashville.

Although he never graduated from college, in 1865, he accepted the position of Professor of Geology and Curator of the Museum of the Illinois Wesleyan University at Bloomington. Powell had already made several trips to the west and, on those trips, began to formulate an idea of exploring the Grand Canyon.

On 24 May 1869 Powell and nine others – seven of whom were Civil War veterans – set off from Green River, Wyoming provisioned with 10 months of supplies. Only six of the 10 men would finish the trip. Fairly early on, they lost one of their supply boats traversing a rapids they named Disaster Falls though Powell and his men were able to salvage some of the barometers which were crucial to determining elevation which, in turn, was crucial in estimating the remaining travel distance. (Keep in mind that rivers start at some elevation higher than sea level and descend in their flow.)

About a month after this incident and passing through several more dangerous rapids, an Englishman named Frank Gordon became the first to leave the expedition. He walked to a nearby settlement and lived out his life eventually raising a family in Vernal, Utah. The 1869 expedition (Powell would lead a second expedition in 1871) continued down the Green River to the confluence of the Grand River flowing west into Utah. The two rivers eventually merge into the Colorado where, over the ensuing two months, they encountered yet another series of rapids – each seeming more dangerous than the last.

Thinking there would be little or no abatement of the continuing threat, three more men – O G Howland, his brother Seneca, and Bill Dunn – attempted to convince Powell to give up on his quest. When they failed to do so, they left the expedition at a place Powell named Separation Canyon. The decision would cost them their lives when, according to a story Powell claimed he was later told by a Mormon scout named Jacob Hamblin, the men were killed by a party of Shivwits Indians who mistook them for miners that had killed a Hualapai woman on the south side of the river.

The decision of the three men earned an even greater degree of irony because Powell’s expedition reached the mouth of the canyon on the Virgin River (now under Lake Mead) just two days later.

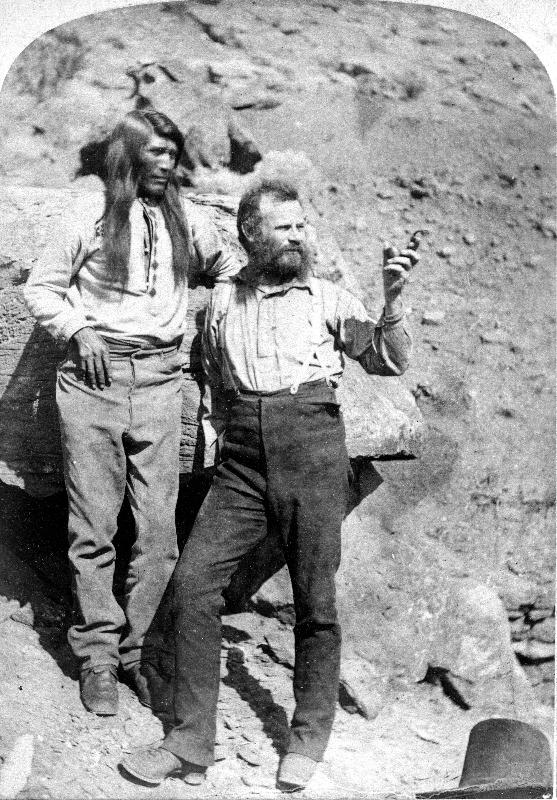

The town of Page, Arizona hosts the Powell Museum. There are no photos of the 1869 expedition but you can see photos of Powell on this NPS website, including this one,

taken during the second expedition.

Returning to the present and continuing my walk east from Powell Point, the paved path ended. Its discontinuation combined with my personal caution and timidity to thwart my ambition to walk the nearly 10 miles from my starting point to Hermit’s rest. I think the paving stopped just beyond Powell Point. Although I walked one stretch of unpaved path, anyone who has walked with me knows I am prone to stumbling. I managed the quarter mile or so walk to Hopi Point without major incident but was daunted by the prospect of attempting another unpaved mile to Mojave Point and yet a second rocky mile to a spot called The Abyss. I opted to take the bus to Hermit’s rest where I grabbed a snack and refilled my water bottle.

Oh, speak again, Bright Angel.

I don’t think the name of this trail references Shakespeare but I certainly heard its call. Intent on reaching Hermit’s Rest, I passed by the Bright Angel Trailhead with barely a glance on my early morning constitutional and, having stopped at most of the viewpoints between the two, I rode a pair of buses to the Bright Angel stop. Rested and refreshed, I was ready to tackle at least a segment of the trail the Park Service describes as

the park’s premier hiking trail. Well maintained, graded for stock, with regular drinking water and covered rest-houses, it is without question the safest trail in Grand Canyon National Park.

Though it has been rerouted and improved since the Park Service took it over in 1928, the trail still principally follows the Bright Angel Fault line as explained in the sign below.

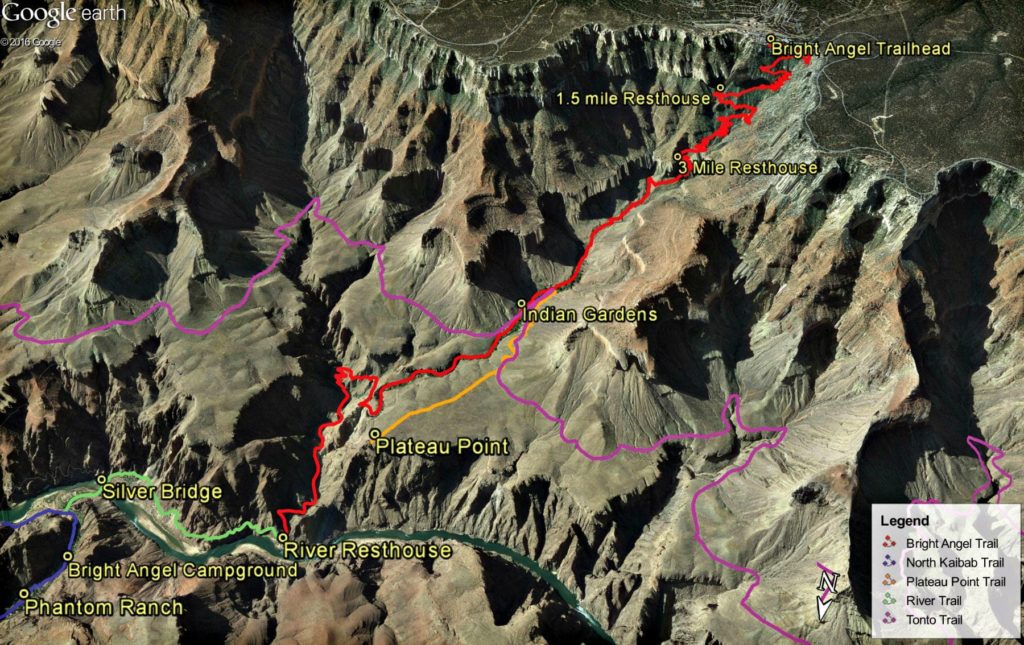

The trail winds along for eight miles from the trailhead to the junction with the River Trail at the River Resthouse with an elevation change of 4,380 feet. Here’s what Google Earth sees (image taken from the Grand Canyon Adventures website).

In one of its brochures, the Park Service suggests several places for day hikers to stop while strongly discouraging any attempt to hike to the river and back in a single day. The shortest walk is not quite 2/10 mile one way, has an elevation change of 132 feet (about the equivalent of a 13 story building), and is described as “Not too steep, good to experience a view from within the canyon”.

The brochure also provides instructions on proper behavior when hikers meet mule riders. If the warnings they provide are insufficient, you are quickly reminded both visually and olfactorily that the trail is heavily used by the guided tours taken on mules.

I encountered less scat farther down the trail. Somehow, I imagined that the mules see this view at the top of the trail

and think, “I can’t believe I’m doing this again!”

I planned to go no farther than the 1.5 Mile Resthouse which would involve a descent of slightly more than 1,100 feet and, of course, its corresponding ascent. The “Plan Your Visit” brochure suggested two other intermediate stopping points – the first switchback and the second tunnel. You can see how far I walked in the photos here.

I was nearly done in by the time I returned to the trailhead but I was also determined to walk to the beginning of the Trail of Time. I boarded the bus and rode it three stops to the Shrine of the Ages where I rejoined the South Rim Trail and staggered to Yavapai Point then three quarters of a mile beyond that to Mather Point – named for the first director of the National Park Service – where the crowds had grown so thick that I didn’t bother taking any photos.

Instead, I walked through the Visitor Center, got on the bus and returned to Market Plaza and the Yavapai Lodge where I ate at the hotel restaurant for a second consecutive night. After dinner, I shuffled the remaining quarter mile to my room, popped whatever N-SAID I could conveniently grab from my stash, and, utterly exhausted, collapsed within minutes.

Note: In keeping with my 2022-2023 reformation of the blog into shorter entries, backdated to maintain their sequence, any comments on this post might pertain to its new configuration. See the full explanation in the post Conventions and Conversions.

-

It’s just a shot away – Prizren

March 6, 2026 -

Some things looking better, baby – Getting into Kosovo

March 4, 2026 -

Here, where the sky is falling – Kukës

March 2, 2026 -

That’s when we fall in line ’cause we got Berat

February 27, 2026 -

Walking on the big stuff – a climb to Tragjas

February 25, 2026

2 responses to “Picking up where I left off”

The sunrise pictures are amazing!!

the sunrise picture is inspiring me to start planning my trip. thank you for coming ‘out of the moment’ long enough to take it and share. But I get the mentality–my first trip to London I never took the camera out of the hotel room.