I wrote previously that Istria has a volatile history and promised I’d detail it during our visit there. We’re there on a bus taking us from Opatija to Motovun – one of the best preserved traditional hill towns on the peninsula. What better time to discuss those details.

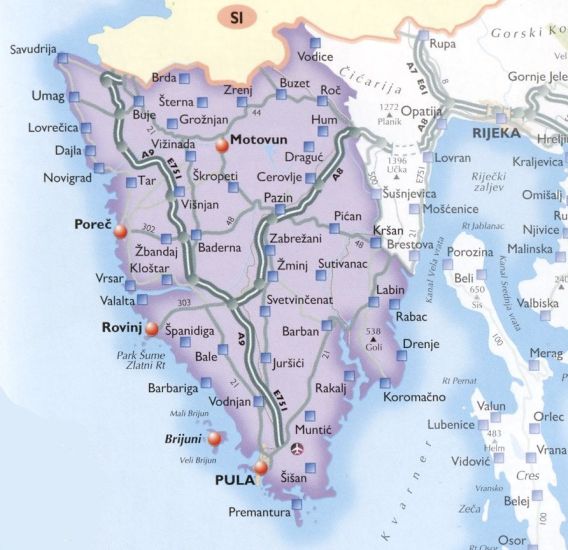

Istria is the triangular peninsula making up the westernmost part of Croatia. It’s bordered by Slovenia on the north and the Adriatic on the other three sides. Recall that Tito wanted to incorporate Trieste as part of Croatia. One reason the Allies opposed this is that it would have required Croatia’s partial annexation of part of present-day Slovenia allowing AVNOJ, as the administrative arm of the Partisans, to then alter the pre-war boundaries of the Yugoslav republics. Trieste is just a bit north and west of the map below.

Let’s look at how the largest peninsula in the Adriatic came by its name. The most common account is that the name derives from a prehistoric Illyrian tribe who inhabited the regions and were known as Histri. Alternatively, it might be derived from Hister – the Roman name for the Danube.

Listening to our local guide, I couldn’t help but get the feeling that the people of Istria are so accustomed to seeing control of the territory shift between one empire and another or one government and another that they greet any new ruler with an indifferent shrug. In a story about Istrian wines, a local winemaker, Ivica Matošević, told the Huffington Post, “My grandfather lived in Austria, my father was born in Italy, I was raised in Yugoslavia, and my daughter was born in Croatia, yet nobody ever moved.”

Of course, I now had to understand how all these national shifts came about. Here’s a recap of what I learned.

Istria’s ancient History-uh.

The Romans conquered much of the peninsula in 178-177 BCE and established the port city of Pietas Iulia at what is now Pula near the southwestern tip of Istria. Pula is the only city that shows clear evidence of the Roman presence with its forum and amphitheater still intact. However, many other settlements on the peninsula date from the time of Roman rule which lasted until the fall of the Empire in 476.

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, a pattern developed over the ensuing several centuries that would become all too familiar. First, the Ostrogoths moved into the void left by the Romans and, for half a century or so, pillaged what settlements existed. The following half century belonged to the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) empire. By 599 the Lombards had moved up from Italy and annexed Istria.

Istria saw a period of centuries of near constant conflict beginning in the early part of the seventh century with the first invasions of Avars from Carpathia and, for the first time, various Slavic tribes. The Avar-Slavic invasions conquered most of the inland territory while the coastal towns put up strong resistance. Thus, Istria saw attacks from the Lombards from the west, Slovenes from the north and Croats from the south and east. The latter two had the greatest success more or less Slavicizing the peninsula.

Near the end of the eighth century, the Frankish Kingdom of Italy (part of Charlemagne’s Empire)

annexed Istria. But by this time the population was mainly Slavic so, of course, some conflict was baked in. Even during Charlemagne’s rule, the Slavs and Croats were restive enough to negotiate a measure of self-governance at the Assembly of Rižana in 804. They failed in their attempt to gain ownership of their land.

After Charlemagne’s death in 814, squabbling between his sons further weakened the Frankish rule and Istria, which was an important land bridge between the Apennines and the Balkans, was nominally batted back and forth between several Germanic Dukes throughout the tenth and eleventh centuries. The feudal infighting more or less allowed the Slavic Istrians to tend to their own business in their own way.

And then along came Venice.

The Venetians, who had been gradually growing more powerful, set their sights on the peninsula and in 1145 conquered Pula in the south and Koper and Izola (in today’s Slovenia) in the north. The Venetians slowly controlled more of Istria proceeding primarily along the coast but in 1278 they moved inland and took control of Motovun – the town we’re on our way to visit.

While Venice controlled the western side of the peninsula, the inland and east coast maintained its ties with Germanic rule and, by 1374, became part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Although they traded and inter-married, two groups, the Benečani who were loyal to Venetian rule and the Kraljevci – loyal to the Austrians – continually waged battles over pastures, woodlands, farmland, and boundaries, in the process destroying crops, stealing livestock, and killing witnesses. Both the Austrian and the Venetian administrations had bigger concerns and chose not to intervene seemingly content to let the groups fight among themselves.

As late as 1494, the region looked like this:

You can see that Venice controlled most of Istria with Austria holding a piece of what is now the Slovenian coastline and a small spike into the center of the peninsula.

With the fall of the Venetian Republic in 1797, the real fun began. Napoleon quickly filled the power vacuum and just as quickly decided to swap the peninsula along with what had been the Venetian controlled part of Dalmatia to Austria for the Netherlands and Lombardy. They wrapped up this deal in the Treaty of Campo Formio. By 1805, the Frenchman had a change of heart and had his armies re-occupy Istria making it part of his Italian Kingdom. That lasted four years until he transferred control of the territory to his Illyrian Provinces thus bringing Istria under a civil Croatian administration for the first time.

Napoleon’s defeat at the Battle of Leipzig in October 1813 eventually led to the Hapsburg Empire regaining control of Istria by 1814. This time, the Austrians built a unified system of public administration in the region maintaining their control of the peninsula until the end of First World War. During this time, they established Trieste as the territorial capital.

Between the Wars.

Unfortunately, the end of the Great War did nothing to stabilize who controlled the peninsula and, as Istria got swatted back and forth like a cat toy dangling from a string, segments of the local population suffered grievously. The degree and manner of their suffering was solely dependent on whether the paw batting them about belonged to an Italian or Slavic cat. The newly reestablished Kingdom of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs (later the Kingdom of Yugoslavia) signed an agreement with Italy in 1920 effectively ceding control of the peninsula to their western neighbor.

However, a chap named Benito Mussolini who had founded the Fasci of Revolutionary Action in 1914, was rising in power. He became the Duce of Fascism in November 1921 and 11 months later became Prime Minister of Italy. The fascist movement, predicated on revolutionary action, proletarian nation theories, one-party states, and totalitarianism began a program of forcible Italianization by suppressing the culture of the native Croat and Slovene population.

During the period between the two world wars, Italians attempted to eradicate as many traces of Croatian and Slovenian public and national life as possible. They abolished all Croatian schools, cultural institutions, and associations. Croatian names were Italianized and the Slavs were prohibited from using their mother tongue. By 1934 the Slavs were no longer permitted to use Croatian or Slovenian in celebrating the Catholic Mass – one of the signal achievements of Bishop Josip Strossmayer and among the reasons he is so honored in the Balkans to this day.

The upshot of this suppression led to two very different responses. On one side, tens of thousands of Croats emigrated from Istria. Most returned to Croatia but others left Europe mostly emigrating to South America never to return. The other was the formation of an organization known formally as the Revolutionary Organization of the Julian March T.I.G.R. It was commonly known simply as TIGR for Trieste, Istria, Gorica, and Rijeka and aimed for the repatriation of those territories to Yugoslavia.

While it’s considered one of the first anti-fascist resistance movements in Europe, the fascists governing Italy viewed it as a terrorist organization (once again showing that one person’s freedom fighter is another person’s terrorist). There’s no question that TIGR used guerilla tactics. They carried out several bomb attacks in Italy and in Germany – particularly after the Anschluss in Austria in 1938. They successfully assassinated Italian military personnel, police officers, civil servants, and prominent members of the National Fascist Party. The situation changed with the outbreak of the Second World War. However, despite being on the “right side” before the war, their strong anti-totalitarian ethic meant they would suffer under Tito’s regime.