The Siege of Sarajevo was long and heartbreaking. Living conditions were hellish. Destruction of property and lives was incessant for more than four years. Over that period, nearly 14,000 people were killed and scores of thousands injured. But the people persisted. Their spirit survived and today the city shows ever more signs of resurrection. The people of Srebrenica never had that chance.

I write in detail because forgetting is easy. I write in detail because superficiality is easy. I write in detail because, as Milan Kundera reminds us, “The struggle of man against power is the struggle of memory against forgetting.”

WARNING: BEFORE YOU CONTINUE READING, BE AWARE THAT THIS AND THE FOLLOWING POSTS CONTAIN PASSAGES AND IMAGES THAT MANY MIGHT FIND DISTURBING.

Before the Massacre.

I’m going to try to avoid a detailed reiteration of issues and events leading to what was, perhaps, the height of the criminality that occurred in the course of these particular Balkan Wars. But there are a few broad facts you need to keep in mind: Recall the discussion of the blobby map of B&H that has divided the country into the Republika Srpska and the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Keep that image in place. Remember that the Bosnian Serbs declared the Serbian Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina in January 1992 then boycotted the independence referendum held on 29 February and 1 March. Keep in mind that by the end of the first week in April, the new Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina had gained international recognition while at the same time the JNA joined Bosnian Serb paramilitaries that later became known as the Army of Republika Srpska (VRS) in an attack on the fledgling state.

All the main parties in this conflict committed atrocities. Croats and Bosnians both mistreated and even murdered Serbs in significant numbers. A handful have come to trial at the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY). In 2012, eight Muslim wartime officials were charged with torture and abuse and put on trial in Bosnia. But no case can be made that either of these groups was as methodical and determined as the Serbs in attempting to create ethnically homogeneous areas where none had existed.

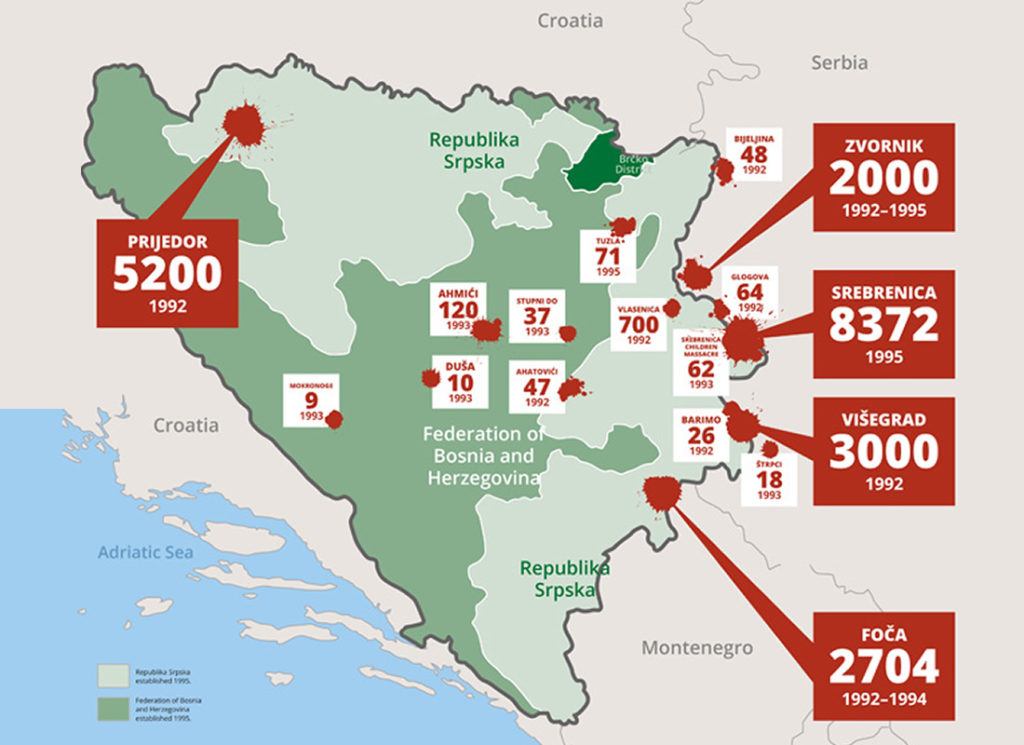

In addition to the unceasing attacks on Sarajevo, the Serbs, knowing there could be no territorial unity in the Republika Srpska without control in the east launched an attack on the area of Podrinje – about 120 kilometers south of Srebrenica. This primary assault occurred between April and June 1992. And here they began the pattern of “ethnic cleansing” or using sieges, property destruction, and starvation to try to displace people or, when that failed, simply resorting to mass murder of the sort that would culminate in the massacre at Srebrenica more than three years later. While it includes some instances of Croat violence as well, this map from the Remembering Srebrenica website clearly shows the pattern:

The numbers in the red blocks all represent acts Serbs committed against Bosniaks. Here is one conclusion of the ICTY:

Once towns and villages were securely in their hands, the Serb forces – the military, the police, the paramilitaries and, sometimes, even Serb villagers – applied the same pattern: Muslim houses and apartments were systematically ransacked or burnt down, Muslim villagers were rounded up or captured and, in the process, sometimes beaten or killed. Men and women were separated, with many of the men detained in the former KP Dom prison.

And the march was relentless. By one estimate, the VRS, with financial and logistical support from Serbia and the JNA, destroyed nearly 300 villages in those first three months displacing more than 70,000 Bosniaks. The Bosnian Institute in the UK has documented 3,166 (mainly civilian) deaths from that period.

Serbian forces had gained control of the area around Srebrenica in early 1992 but the Army of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina (ARBiH) recaptured the town in May. By January 1993, they had captured territory to the south and west and expanded what was being called the Srebrenica enclave (because it was akin to an island in the midst of Serbian territory) to an area of 900 square kilometers.

Serbian forces counterattacked and recaptured so much territory that the enclave shrank to a mere 150 square kilometers. This prompted Bosniak residents in outlying areas to converge on Srebrenica which was the largest city in the area. I use the term city with some caution. In 1991, the area around Srebrenica had a population of about 36,000 people – 75 percent of whom were Bosnian Muslims. The town itself counted 5,700. This initial influx of refugees swelled the population of the town to nearly 60,000.

[Image from Remembering Srebrenica.org.uk – Ron Haviv.]

Throughout late 1992 and until March 1993, the Serbians subjected Srebrenica and the surrounding area to more or less constant and generally indiscriminate attacks from all directions though they often focused on the town of Potočari about seven kilometers north of Srebrenica because they saw it as a strategic point of the larger town’s defense. Potočari is now a home to a cemetery for identified victims of the massacre and a Srebrenica Memorial as well.

By March 1993, the Serbs changed tactics and placed the city under siege – much as they were doing to Sarajevo. They cut off as much of the water supply, food, medicine, and electricity as they could with the primary goal of literally starving the city. The French General heading the United Nations Protection Force (UNPROFOR) visited the city at that time and reassured the citizens that they were under UN protection and that “he would never abandon them.”

During the next month, and over the objections of the Bosnian government, the UN evacuated several thousand Bosniaks from Srebrenica. Though they almost certainly saw their efforts as humanitarian – and in some sense they were – these evacuations also made the UN complicit to some degree in the Serbian goals of ridding the area of its majority Muslim population.

The UN Safe Area.

On 16 April 1993, three days after the Serbs had issued an ultimatum to the UNHCR demanding the surrender and evacuation of Srebrenica, the United Nations Security Council passed a resolution that demanded that “all parties and others concerned treat Srebrenica and its surroundings as a safe area which should be free from any armed attack or any other hostile act.”

By early May, a few weeks after the first UNPROFOR troops comprised mainly of Dutch units had arrived, the general commanding the ARBiH troops in the area and Ratko Mladić agreed on measures covering not only the Srebrenica enclave but the adjacent enclave of Žepa as well. Under the terms of the new agreement, Bosniak forces within the enclaves would hand over their weapons, ammunition, and mines to UNPROFOR, after which Serb heavy weapons and units threatening the demilitarized zones would be withdrawn.

Although both sides violated the agreement almost from the outset, the JNA and VRS forces held distinct advantages in position and weaponry. In truth, the ARBiH force remaining in the enclave was neither well organized nor well equipped. The Serb forces continued their slow dance of refusing to withdraw their forces while continuing to displace the ethnic majority because of alleged Bosnian violations of the terms of the agreement.

[Photo from npokennis.nl].

Over the ensuing 24 months the situation continued to deteriorate as fewer and fewer supply convoys made it through the Serbian blockade to the enclave. Even the UN forces started running dangerously low on food, medicine, ammunition, and fuel eventually being forced to start patrolling the enclave on foot. Many Dutch unit troops who left the immediate area were often captured and those troops weren’t permitted to return – thereby dropping their number from an initially meager 600 to a scant 400.

On 7 July 1995, while under a Serbian assault that began the previous day, the mayor of Srebrenica reported that eight residents had died of starvation. Five UNPROFOR observation posts in the southern section of the enclave fell to the Serbian advance. Dutch soldiers reported that the Serbs were “cleansing” (e.g. burning to the ground) the houses in the southern part of the enclave.

As those early successes continued, and the international community failed to respond, Radovan Karadžić issued an order on 9 July to capture Srebrenica and on 11 July, Mladić took his triumphant walk and gave the interview posted in the second entry of this journal.