Remember that I called the setup at Rydges Sydney Airport Hotel that had an airport check-in just across the street brilliant. It not only allowed me to avoid any potential chaos and crowds at the main terminal but this proximity and convenience also permitted a later start to the morning than would have been necessary otherwise.

Even had it necessitated an earlier start, this was a relatively light day. Other than meeting the flight to the place the Mumirimina People would have called Nipaluna (and that we call Hobart) and completing the other necessities of travel, all I had planned for this day was an evening visit to Bonorong Wildlife Sanctuary a half-hour drive north of the city’s CBD.

I acknowledge that I am on the land of the Mumirimina People who did not survive colonization. I extend my respect to the Palawa/Pakana (Tasmanian Aboriginal Community) of Lutruwita and acknowledge their custodianship. The Dreaming is still living. From the past, in the present, into the future. Forever. I would also like to pay respect to the Elders past, present, and emerging and extend that respect to other Aboriginal people present.

The flight to Hobart was uneventful as was my SkyBus ride from the airport to the CBD. (I will, as usual, and as a courtesy to the average reader, refer to most places by their broadly recognized names.) I was able to check-in to Hadley’s Orient Hotel (rather old and delightfully old school),

stop for lunch at MS Korea on Elizabeth Street, and have a bit of a wander around the neighborhood. Photos are here.

I had what the menu called “Stir-Fried Soy BBQ” which seemed to me to be breaded tofu with vegetables and rice. It was filling and a nice break from the typical RS fare I’d been having.

A dark history

As challenging as the history of mainland Australia might be, it’s possible that the history of the invasion and colonization of what was at the time called Van Diemen’s Land is even blacker. I feel compelled to address it.

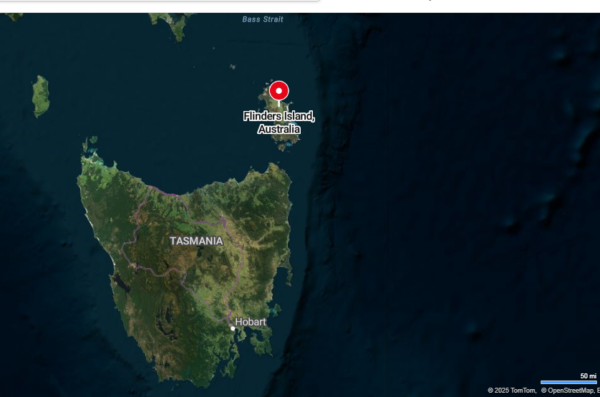

If you carefully read (or listened to) my Acknowledgement of Country, you would have noticed one important difference from the others. This is that the Mumirimina People didn’t survive colonization. Most estimates place the population of Palawa on Lutruwita as having between 3,000 and 15,000 people in 1803 when Lieutenant John Bowen established the first British settlement at Risdon Cove (about 10km north of Hobart’s CBD on the eastern side of the Derwent River. In time, most of the Palawa who did survive were forcibly resettled on Flinders Island (Wybalenna).

[From Bing Maps]

By the time of its closure in 1847 only 47 remained alive.

In 1871 when the settlement at Oyster Cove was officially closed, only two were still living. For 4o,ooo years or longer Palawa had lived on and sustained Lutruwita as the southernmost people on earth. In less than half a century, less time, in fact, than the British required to rename Van Diemen’s Land as Tasmania, nearly all of the Palawa were dead.

Despite relatively sparse populations clashes began soon after the British arrived. (There were 49 initial settlers and Tasmania is about 68,400km² so even if the Indigenous population was as high as 15,000, the number of Palawa living in that particular area was likely small as well.) The first belligerent encounter occurred on 3 May 1804. The specifics of what happened there has become a matter of historical dispute.

There’s an official record of the clash that reports between three and six Aboriginal people killed. Based in part on an 1830 inquest in the matter some historians concluded that at least 30 and perhaps as many as 100 died – though there’s little hard evidence to support that number. In his book Reminiscences, John Pascoe Fawkner claims at least fifty Aboriginal People killed. At least one boy, who would be named Robert Hobart May, was abducted and forcibly baptized in a practice that had been commonplace in Australia since 1816. (As I see it, in the end, the accuracy of the number of people killed is irrelevant. The Palawa rightly saw the British as invaders and were protecting the Country that had sustained them for uncounted generations. The British saw the Palawa as primitive and valueless and, while they were often defending themselves, felt justified in any stance to protect themselves, even one that led to the extinction of an entire people. You, reader, are free to disagree.)

Black War

The first of the Frontier Wars began in New South Wales in 1794 – six years after the First Fleet sailed into Sydney Harbour and settlers began establishing farms along the Hawkesbury River. Conflicts in the colony flared off and on for 22 years until Governor Lachlan Macquarie sent troops from the 46th Regiment of Foot in 1816 followed by a proclamation ordering magistrates and troops to support settlers in driving off “hostile Aboriginal people” essentially indemnifying soldiers and settlers against charges of murder. However, the wars on the mainland are difficult to classify because the fighting was sporadic and mainly guerilla in nature with few formal battles.

The conflict continued throughout Australia until the first third of the twentieth Century. The Black War in Van Diemen’s Land lasted a relatively short but brutal eight years beginning in 1824 and formally ending in January 1832. (Wanting to distance the colony from its grim history as a penal settlement and the associated brutalities of convict transportation and ethnic conflicts with the Aboriginal people, the island’s name officially changed in 1856 when Queen Victoria approved an Order-in-Council.)

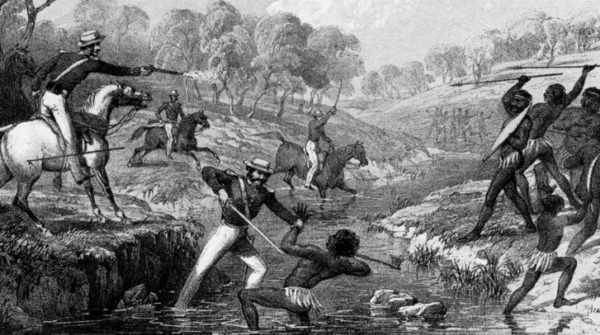

Rather than formal battles, skirmishes such as the one at Risdon Cove continued and were likely instigated by both sides. The under armed Palawa, fighting British cannons and firearms with their traditional weapons of spears and clubs, staged persistent guerilla type raids on British farms and settlements that were competing for the island’s limited resources and, more importantly, that they saw as an invasion of Country. The British fought back employing both defensive and offensive tactics.

[From Wikipedia – Public Domain]

Unlike the conflicts on the mainland, where some Indigenous People sought refuge away from the settlers, Tasmania’s size left little space or resources for the Indigenes to employ this strategy. The inescapable proximity intensified the animosity between the combatants. Raids, ambushes, and massacres were inflicted by and on both sides.

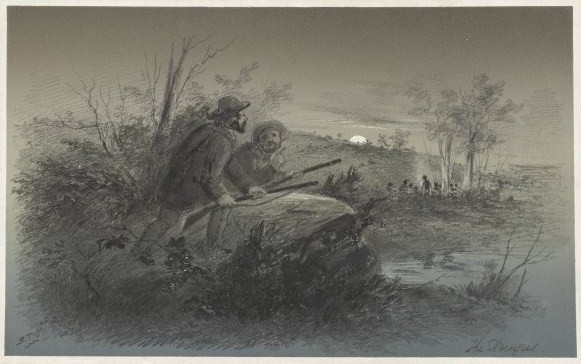

Facing what was for him an untenable situation, in 1830, Lieutenant-Governor George Arthur implemented a military strategy with a goal of capturing the surviving Palawa and relocating them to a controlled area. This strategy was called

The Black Line.

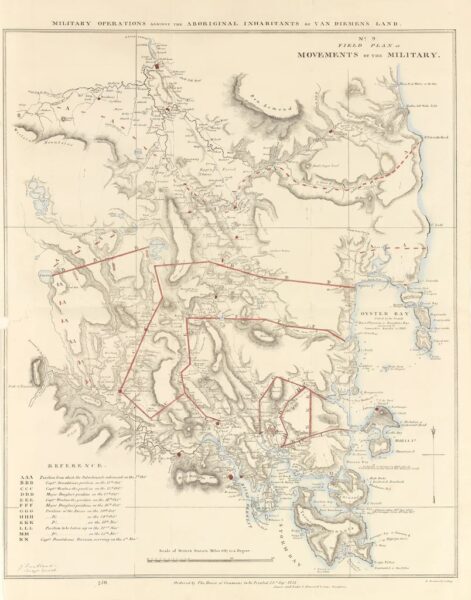

The Black Line employed more than 2,000 soldiers, settlers, and convicts with the latter group including some who had been granted tickets of leave and others who were still serving their sentences. They formed a sort of human chain stretching from west to east across the settled areas of Van Diemen’s Land. The idea was to drive the Palawa onto the Tasman Peninsula where they could be captured.

[The Black Line Campaign – From ArtArk]

Arthur invested substantial resources and extensive planning in the effort but the operation failed. The maneuver required the participants to maintain a continuous line while attempting to navigate through dense unfamiliar bush. The Palawa used their familiarity with the challenging terrain to generally evade the line and only a few were captured.

The failure prompted the use of alternative strategies to address the continuing conflicts. Principal among them was George Augustus Robinson’s

Friendly Mission.

(Like the promises they did not keep)

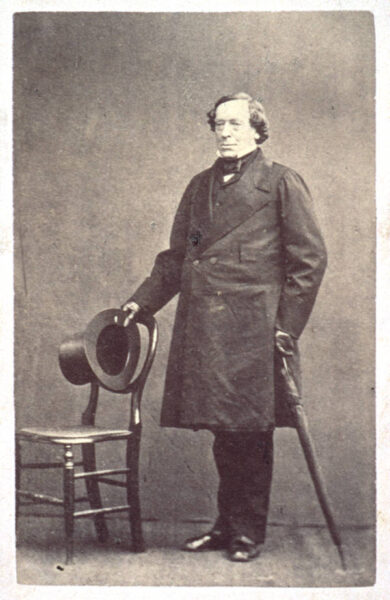

Robinson was a British builder and an unordained preacher who had been appointed Chief Protector of Aborigines in 1829. The goals of his “Friendly Mission” were to establish peaceful relations with the Indigenous People and to persuade them to agree to relocate to a settlement where the government would protect them and provide for their needs.

[George Robinson – From Wikipedia – Public Domain]

Robinson, who learned several local languages and customs, was undoubtedly sincere in his efforts to secure some sort of peaceful coexistence between the Palawa and the British. However, his mission also has to be seen as placing primacy on colonial interests where ending the conflict would ultimately secure the land for European settlement.

Combined with the psychological impact of the Black Line which created a sense of inevitability around European dominion by underscoring the futility of continued resistance, Palawa leaders began to view Robinson’s efforts as a viable alternative survival strategy. Several Palawa groups agreed to move to the settlement at Wybalenna or Flinders Island in the Bass Strait.

Unsurprisingly, the reality of life at Wybalenna failed to meet Robinson’s promises.

[Residences of the Aborigines by John Skinner Prout – Digital Classroom – NMA]

Inadequate housing, insufficient provision of food and clothing, and the spread of European diseases combined with the stress of being unable to practice their traditional culture and lifestyle decimated the population. Wybalenna’s peak population was 220 in 1835. By 1847, only 47 people – 15 men, 22 women, and 10 children – remained alive and they were then relocated to Oyster Bay. Within two decades all but four had died.

Next post, Bonorong.