In previous entries, I’ve touched upon some of the contrasts that make Sarajevo Sarajevo. The mix of ancient and modern. The fusion of east and west. The tolerant juxtaposition of religious belief and practice. And, above all, the resolute display of the best of the human spirit in the face of the unimaginable worst of human nature. Today, my second full day in Sarajevo, will fittingly be the darkest and lightest of the trip. It will be the day when the war will be more present than on any other. It will be the day when death and destruction meet hope and survival. It will be the day I will most wish I could forget but it will also be the day I most want to remember.

It’s impossible to visit Sarajevo without confronting, both tangibly and intangibly, the city’s experience of the years 1991 to 1995. In some sacred public places, visible scars remain. We saw them on the Eternal Flame memorializing the sacrifices of Sarajevans in the Second World War. Other public places, like the City Hall Building have undergone extensive cosmetic surgery requiring you to, quite literally, go below the surface to find those reminders. Both places bring to the present that dark period of the past.

Today’s story will be long and difficult but it begins with beauty and ends with joy. Please stay with me for as long as it takes to arrive at those closing grace notes.

Early in the morning, a moment in the hotel hinted that this day could hold something special. Sitting in the lobby waiting for the group to gather for our visit to the Tunnel of Life and later to even more bleak Gallery 11/07/95, my ears perked up at the sound of a very familiar and very surprising voice. Piping over the Hotel Europe’s sound system was none other than the brilliant Eva Cassidy singing Songbird. Of all the places I might expect to hear Eva Cassidy, I doubt the Hotel Europe in Sarajevo would have ever made the list. Any day that starts with Eva Cassidy singing is going to be a good day.

Before we board the bus for the ride to the Tunnel of Life, here’s Eva singing the song playing in the hotel that morning.

Next, before I start writing about the war and the siege, I need to introduce you to a vital symbolic part of Sarajevo that we spotted on yesterday’s walk.

The Sarajevo Roses.

On 20 March 1993, an 11-year-old girl playing in the street outside her home became one of more than 11,000 civilians and 1,600 children who were killed by Serbian shelling during the 1,425-day siege of Sarajevo. The mortar left a small crater from the explosion and after the war ended in 1995, many of these craters were painted red as a memorial to the blood spilled in the spot and in memory of the victim.

The girl’s name was Irma Grabovica. Her father, Fikret, is now the president of the Association of Parents of Children Murdered in Besieged Sarajevo – an organization working to preserve the roses that remain. Though scores of these roses dotted the city in the immediate aftermath of the war, Sarajevo has been rebuilding itself in the quarter century since. As a result, they say only a dozen are left.

An American photographer, Roger M Richards, who produced a documentary film about the Sarajevo Roses called them, “a symbol of the city, its struggle to survive the siege and afterward when all was destroyed.”

He sees them as “a metaphor for the city, and the petals of these shell impacts mark the pavement like scars on the heart; a terrible beauty. The red is not only for the color of the flower but of the innocent blood spilled on Sarajevo’s streets.” And yet, within the death and destruction, he sees the hope and life that is the soul of this city, “The real roses are the people of Sarajevo, who continue to bloom. Roses still grow even in the middle of destruction.” As does Sarajevo.

Onset of the Siege of Sarajevo.

From 1945 until his death in 1980, Marshal Tito, through his own brand of independent socialism/communism, the force of his strong personality, and abetted by the force of the national police, kept a lid on the long simmering ethno-religious tensions in Yugoslavia. Foreseeing no leader to replace him, he passed a constitution in 1974 creating a pathway for the various republics to declare their independence. Nationalist sentiment experienced something of a rebirth in the 1980s with most of the republics tending to favor independence. The Serbs preferred a more centralized Serboslavia that concentrated national control in their hands.

Except in Bosnia and Herzegovina and, perhaps Slovenia, each republic had a clearly defined national and religious majority. B&H was a three-minority republic with Bosniaks comprising the largest of those at 43 and one-half percent. In much of B&H, but particularly in the area in and around its capital Sarajevo, the population had a history of living in harmony if not amity.

Thus, in November 1990 B&H held its first multi-party parliamentary elections and the three main ethnic groups formed a loose coalition to complete the ouster of the Communist Party. However, by the middle of 1991, both Slovenia and Croatia had declared their full independence. While not an internal matter in B&H, this step inspired nationalist feeling and, stretched to the breaking point the links that had theretofore held the governing coalition together. The Bosniaks and Croats strongly favored B&H’s independence while the Serbs inside and outside B&H wanted a greater Serbian state under the banner of the Yugoslav federation.

By October 1991, not only had the Serbs pulled out of the coalition, they had formed their own body – The Assembly of the Serb People of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Their withdrawal came just days after the B&H National Assembly had issued a declaration of Bosnian sovereignty. Following the procedure set forth in the 1974 constitution, the Bosnians scheduled an independence referendum for 29 February and 1 March 1992. The Serbian Assembly then declared the establishment of the Serbian Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina in January of the same year.

The Serbs boycotted the referendum depressing voter turnout to a reported 63 percent. However, of those that voted, more than 99 percent voted in favor of independence. Bosnia and Herzegovina declared independence on 3 March 1992 – gaining recognition by Croatia the following day, the European Community on 6 April, and the United States on 7 April.

Even before the declaration, an incident at a wedding alleging that Muslims, angered at the wedding party carrying the Serbian flag through the Baščaršija, killed the groom’s father further strained ethnic tensions. (The Old City or Stari Grad of Sarajevo was the one part of the city that was close to exclusively Muslim – nearly 78 percent according to a 1991 census – which would indicate that such a display of Serbian nationalism would be particularly provocative.) From the time of the declaration, sporadic fighting broke out between Serbs and government forces across the territory beginning when Serb paramilitary forces attacked Bosnian Croat villages around Capljina on 7 March and the Bosniak town of Goražde on 15 March.

After the incident at the wedding, Serb paramilitary forces set up barricades and sniper positions near Sarajevo’s parliament building seemingly threatening a possible coup. Crowds of Sarajevans took to the streets to thwart the possibility.

On 5 April, the day before the EU recognition, ethnic Serb policemen attacked national police stations and an Interior Ministry training school. The attack killed two officers and one civilian prompting Serbian President Alija Izetbegović to declare a state of emergency hoping the international community would deploy a peacekeeping force. No such response came.

[Credit-jaimesilva-via-Flickr-CC-BY-NC-ND-20-CNA.]

(This bridge will be the site of another tragic murder that I’ll discuss in another post.)

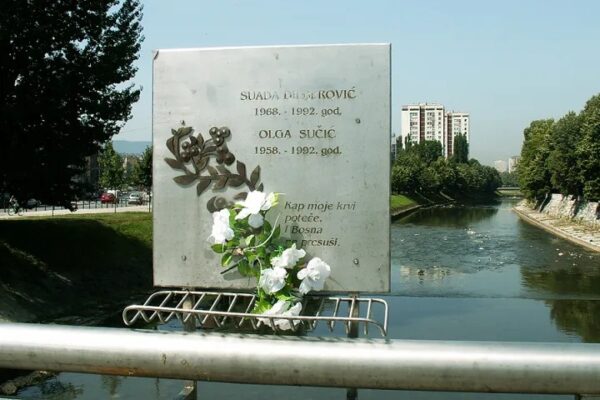

This is considered the beginning of the siege because later that day, Serbian paramilitary forces again set up barricades and sniper positions at Sarajevo’s parliament building. As they had the month before, Sarajevans took to the streets in protest. Some reports estimated the marching crowd numbered 100,000. As they began moving toward the parliament building, gunmen shot and killed two young women – Suada Dilberović, a Bosniak, and Olga Sučić, a Croat. They’re regarded as the first casualties of the siege and the bridge where they were killed, once called Vrbanja has been renamed the Suada and Olga Bridge in their memory.

A week passed and with no peacekeeping mission in sight, fighting broke out in force throughout the country. Slobodan Milošević ordered Yugoslav National Army (JNA) forces that had long been mobilizing in the area around Sarajevo into action to “defend” the Bosnian Serbs. The better trained, better equipped JNA marched on Sarajevo attacking the train station and the Old Town with mortars, artillery, and tank fire. They also gained control of the international airport.

With Serbian forces occupying the high ground on three sides of the city, by the end of April, the siege was largely in place.