I acknowledge that I am on the land of the Larrakia People. I acknowledge their custodianship. The Dreaming is still living. From the past, in the present, into the future. Forever. I would also like to pay respect to the Elders past, present, and emerging and extend that respect to other Aboriginal people present.

I realize that much of my writing has focused on gaining an understanding of Australia’s First People but today will have a different focus. In fact, this will be true of most of my time in Darwin which is called Gulumirrgin or Garramilla by the Larrakia People.

He was never there

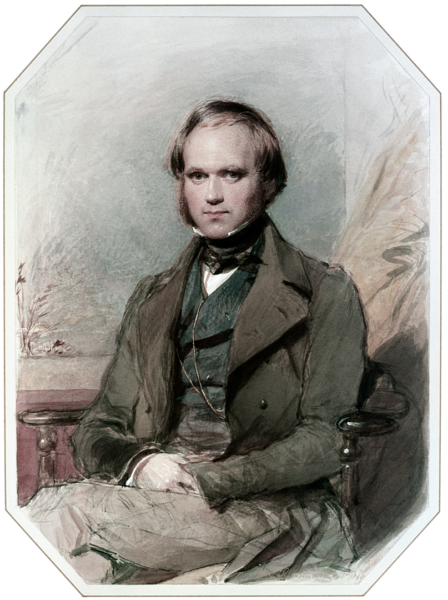

When he was 22 years old Charles Darwin sailed on the HMS Beagle as the ship’s naturalist for nearly five years beginning on 27 December 1831 and ending his voyage on 2 October 1836. As the ship sailed mainly around South America Darwin collected specimens and made observations that would lead to his development of the theory of evolution through natural selection.

[From Wikipedia – Public Domain]

Some three years later, the Beagle sailed into the waters between what we today call East Point and Wagait Beach. Two of Darwin’s shipmates from that earlier voyage, John Clements Wickham and John Lort Stokes named the area Port Darwin after their admired friend and shipmate.

However, it would be another 30 years before the first batch of 135 Europeans arrived. Their main purpose was facilitating trade with the eastern Malay Archipelago. Although they retained the harbor’s name, they named their settlement Palmerston after the then British Prime Minister Henry John Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston.

Still, the community was isolated and communication with the rest of the country difficult. This prompted the start of the construction of the Overhead Telegraph line in 1870. Sometime soon thereafter, workers building the line discovered gold at Pine Creek some 325 kilometers south of Palmerston. This prompted a gold rush and the first mini population boom – mainly an influx of Chinese laborers who would also find work building the railroad line that would connect Palmerston in the north with Adelaide in the south.

[From Journey Beyond Rail]

(This is the same rail line we’re scheduled to take tomorrow to Alice Springs.)

At the same time the town saw an influx of Japanese invited to Australia by the pearling industry. In the 1890s two elements combined to substantially shrink the population. The first was the adoption of a series of laws called the White Australia policy and the second was an 1897 cyclone that killed 24 people and left only eight buildings standing. Still those were enough to house the entirety of the remaining population.

On 1 January 1901, the six Australian states united to form the Commonwealth of Australia. Ten years later to the day, implementing two pieces of legislation, the Northern Territory separated from the state of South Australia moving the administrative structure of the region from state to national control.

Then, on 18 March 1911, perhaps in a bit of a flex, the national government renamed Palmerston as Darwin. Ostensibly, this aligned the city’s name with the more familiar Port Darwin and formalized the honoring of the British naturalist that had likely been the intent of Stokes and Wickham. Palmerston City exists today as a planned suburb some 20 kilometers from Darwin but the scientist himself never reached its shores.

The first devastation of 20th century Darwin

I’ve been a morning person since early in my working career when the circumstances of my job generally had me in my office by 07:00 so, while I’ve carped about some of the early mornings on this trip, it wasn’t terribly surprising that I was up early enough Tuesday morning to take a walk along the Esplanade and Bicentennial Park between breakfast and our scheduled tour of the city and harbor area. Appropriately enough for the day’s plans, I passed several war memorials including this stylized eternal flame

and the cenotaph.

The second stop of the day was a morning tour of the “Defense of Darwin Experience” at the Darwin Military Museum and, other than the photo of this mural beside the Royal Flying Doctor Service Museum,

I remember almost nothing of the morning tour. Going through the Defense of Darwin Experience can do that to a person. Or at least it did to me.

19 February 1942

As the world edged closer to war in the mid 1930s, a military build-up began in and around Darwin. The influx of soldiers that would triple the town’s population triggered upgrades to the Stuart Highway transforming it from a rough dirt track to a major sealed supply road between June 1942 and February 1943.

On 7 December 1941, the Empire of Japan launched its attack on the American Naval forces at Pearl Harbor on the Hawaiian island of Oahu. The next day, the United States declared war on Japan. Three days later Japan’s Tripartite Pact allies Germany and Italy declared war on the United States drawing the country into a global conflict.

On 23 December 1941, Australian Prime Minister John Curtin cabled President Franklin D Roosevelt saying, “The fall of Singapore would mean the isolation of the Philippines, the fall of the Netherlands East Indies and attempts to smother all other bases. It is in your power to meet the situation… we would gladly accept United States commanders in the Pacific area. Please consider this as a matter of urgency.”

And, in an address to the Australian people on 27 December, he said, “Without any inhibitions of any kind, I make it quite clear that Australia looks to America, free of any pangs as to our traditional links or kinship with the United Kingdom.”

The first U S soldiers arrived in Brisbane on 22 December 1941. A stream of American army and naval forces continued to arrive in Australia and by mid February at least four U S ships, the USS Peary, the Army transport Meigs, the freighter Mauna Loa, and the USS William B Preston were in the harbor at Darwin as were perhaps as many as 7,500 American and Australian troops.

[Broadside starboard view of the USS Peary (DD-226) underway (U.S. Naval Institute Photo Archive)]

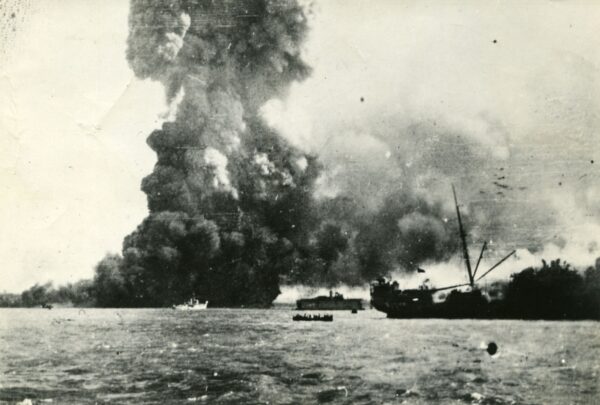

As had happened at Pearl Harbor barely two months earlier, the incoming Japanese aircraft were initially misidentified. Australian radar operators thought they were 10 USAAF P-40s that were returning to Darwin after aborting a flight to Java due to bad weather. Thus, the air raid sirens didn’t sound until the Japanese attack actually began at 09:58 resulting in higher casualties and more extensive damage than might have otherwise occurred. The 188 Japanese aircraft launched from carriers were able to conduct their attacks with relative impunity, leading to significant destruction of ships,

[From Library & Archives NT PH0238-0885]

buildings,

[From Library & Archives NT PH0861-0111]

and infrastructure. It also cleared the way for a second wave of land based bombers at 11:45. At least 236 people died in the two raids of whom 80 (according to the U S Navy) were on the USS Peary.

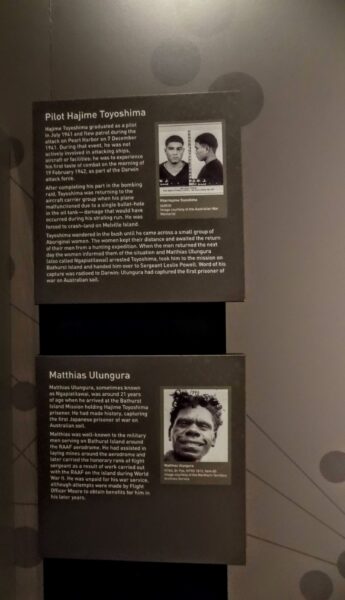

Hajime Toyoshima, a Japanese pilot whose plane crashed on Bathurst Island while returning from his strafing run became the first prisoner of war captured on Australian soil. In a bit of an ironic twist of fate, he was captured by an Indigenous man named Ngapiatilawai (also called Matthias Ulungura).

We won’t cry

(We won’t cry)

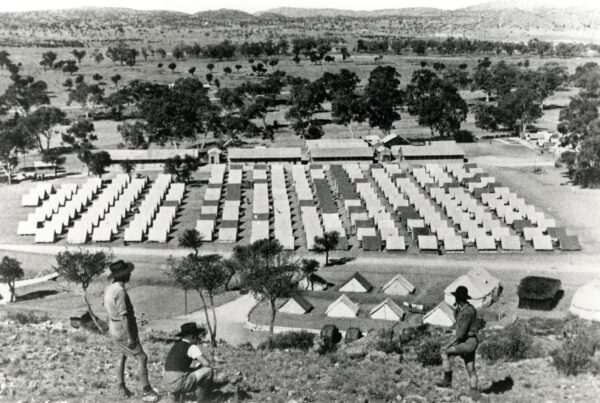

But the Aussies and the Yanks were quick to bounce back. From building a tent city near Alice Springs

[From Library & Archives NT PH0-0425-0013]

that was farther from the coast but that could use the improving Stuart Highway, to

enlisting the help of hundreds or thousands of women

[From Library & Archives NT PH0144-0021]

to accepting the help of Larrakia women, they carried on.

[From Library & Archives NT PH0045-0028]

(This latter was mainly in the form of the Aboriginal Women’s Hygiene Squad whose duties were largely limited to cleaning and maintaining sanitary conditions in the military camp and who never received official recognition and thus were denied the benefits that accompanied formal enlistment.)

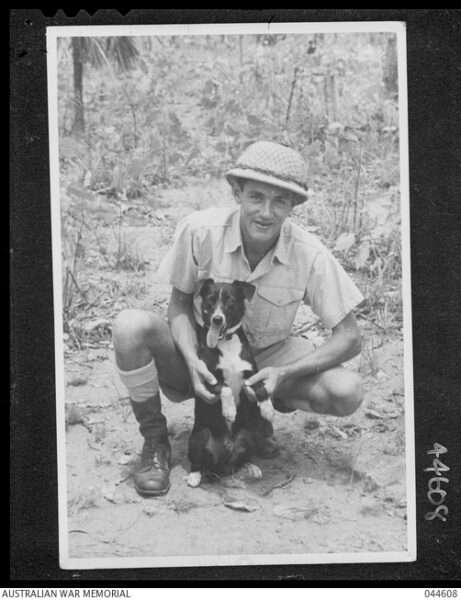

They even had the aid of Gunner, a male kelpie dog

[From Australian War Memorial AWM-7174796-Z]

who was injured in the first attack but whose acute hearing allowed him to distinguish between the sounds of Japanese and Allied aircraft alerting RAAF personnel up to 20 minutes before enemy planes arrived, giving them crucial time to prepare. And this, too, was important.

While the Japanese never launched an invasion of Australia, Darwin remained in their sites for 21 months beyond the initial raid. They launched 64 attacks on the city before ending their assault in November 1943.

In the next post, I’ll tell you about our brief stop at the Northern Territory Museum and Art Gallery, talk about the second 20th century devastation of Darwin, take you on a somewhat typical Todd walk around town, and mention a lovely dinner I shared with D. Links to the photos will have to wait.