The seasons are different in Australia.

I can almost hear all my northern hemisphere friends thinking something along the lines of, “Well, duh! Of course the seasons are different. Everyone knows that when it’s summer in the north it’s winter in the south and vice versa. Tell me something a little less obvious.”

Okay. I’ll start with this: For Australians seasons are defined by their meteorological onset rather than at the solstice as we northerners generally do. For them, summer 2024 will begin as all their summers do on 1 December and, while the weather might be indicating otherwise, for my fellow Americans it will still be autumn. Winter will officially begin on 21 December three weeks after the Australians have celebrated the start of their summer.

The larger point is that, although we may think of our seasons as having fixed dates, even within that construct seasonality is fluid. At the end of today’s flight and bus ride, we will enter Kakadu National Park where the Bininj/Mungguy People are the traditional caretakers.

I acknowledge that I am on the land of the Bininj / Mungguy People. I acknowledge their custodianship and that of all the groups within the Duwa and Yirridja moieties. The Dreaming is still living. From the past, in the present, into the future. Forever. I would also like to pay respect to the Elders past, present, and emerging and extend that respect to other Aboriginal people present.

As we learned in the post Old voices impelling me upward, Australia’s first people have a unique relationship with Country. As we are about to learn, their seasonal divisions are closely tied to that relationship.

Exactly how many seasons are there?

(North wind coming in my way.)

For nearly all of the First People residing in this area of Australia, the calendar, as seen below, has at least six distinct seasons.

[From Mirarr.net Copyright CSIRO Indegenous Knowledge Holders.]

When you live in an area where the climate and resources necessary to your survival is as variable as it is in and around Kakadu, you become acutely aware of the changes in the natural world that necessitate changes in where and how you live and how you can manage them while providing enough for your survival and that of your group. And, you must always be aware of the laws and traditions of Country. The wheel in the image above represents the six seasons of the Kunwinjku group who are part of the larger Bininj People. Curiously, while the First People of this region have divided the year more finely, the non-indigenous people are more inclined to pare down the traditional four seasons to two – the wet and the dry. (And here’s my judgmental observation: The traditional caretakers managed the land for scores of thousands of years leaving it in harmonious balance with what it had evolved to be. The British colonist-invaders have, in barely three centuries, wrought possibly inalterable changes to that environment. Further judgment I leave to you.)

What season are we in?

KUNUMELENG or GUNUMELENG.

Since our visit is in November on the Western calendar, I’ll look in detail at the Kunwinjku season of Gunumeleng and follow that with a brief introduction to the remaining five seasons in sequence. This season roughly corresponds to the time period we mark as mid October to mid December and is the pre-monsoon storm season. During this time, the temperature and humidity begin rising and thunderstorms are common. The local flora becomes increasingly vibrant and the fauna grow more active. In a typical season, the billabongs (oxbow lakes formed when a river changes course and leaves behind a small body of water) might look something like this as the rivers begin their seasonal flow.

[From Odyssey Traveler]

In an unusually dry season like the one on our trip, the landscape looked like this.

Because they so closely monitor environmental changes such as the growth of new grass that would attract larger animals and increased insect activity as a sign of pollination that would allow them to begin harvesting fruit and other edible and medicinal plants, a dry season like this might delay some of the typical activities of the group. Another critical observation they must make is the changes in the billabongs from standing water to flowing streams.

Increasing humidity will alert them to the possibility of thunderstorms and they need to be particularly aware of these outbursts because a lightning strike can ignite a wildfire on the sere plain. All these indicators likely impact the timing of the necessary relocation of their camps to higher ground. Before the monsoons begin, the groups would move to higher ground from the flood plains that they would have occupied since Yekke – the start of the dry time. The stone country provides better shelter from the oncoming monsoon season called Kudjewk.

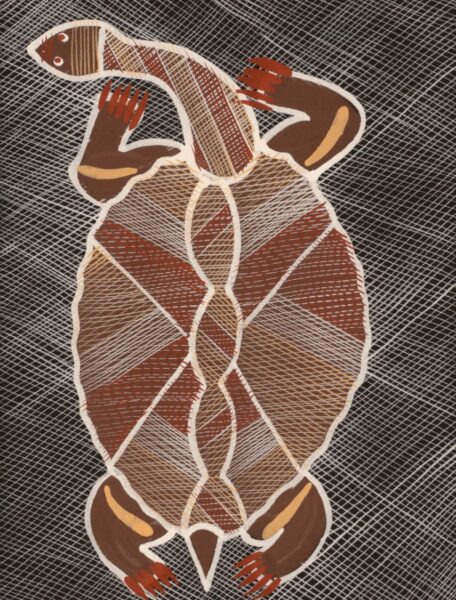

The primary focus of their hunting would likely be the barramundi (a fish I ate often on this trip) as they are migrating into the estuaries to breed, the Kedjebe or Arafura file snake and the long-necked turtle (Ngalmangiyi).

[From Artlandish by Eddie Blitner “Turtle Dreaming”.]

The people would likely start looking for fruit that they could consume and harvest. Among these would be red bush apples,

[From Territory Native Plants NT Government photo]

that fruit plentifully during Gunumeleng, and mankurndal (black plum) in its early fruiting stages.

This transitional season is also a time for Ceremony a ritual that often passes on knowledge to the younger generation from which new leaders will emerge.

KUDJEWK or GUDJEWG.

This is the monsoon season and generally will last from December to March. The people have moved from the flood plains to the stone country. Despite its imposing appearance, food is plentiful during this season because the heavy rains and flooding create an explosion of life. The plentitude of resources likely allows for heightened use of this time to pass down traditional knowledge about the seasonal changes, animal behaviors, and food sources to younger generations.

BANGKERRENG or BANGGERRENG.

Most of this season is concentrated in April. It’s another transitional period when thunderstorms are common. These storms are called Nakurl or “knock ’em down” because as they move in from the east they knock down the early speargrass that might have matured to a height of three or four meters.

[Photo credit: Parks Australia]

Seeds are collected and stored for the dry season. When the clouds turn an orange-red, it’s a signal that magpie goose eggs can be collected and when new speargrass seeds develop, it’s a sign the magpie goose eggs are about to hatch.

YEKKE or YEGGE.

This is a critical time for the the Bininj / Mungguy People. One of the signals is the shift in the wind as it begins blowing from the north and east to the west. They will begin to move from the stone country back to the flood plain during this cooler dry season that spans May and June. Perhaps the most important observation is watching for the Darwin Woolybutt (Eucalyptus miniata)

[From Wikipedia By Murray Fagg – , CC BY 3.0 au]

to flower. This is the signal to begin “cleaning the country” by conducting controlled burns in the woodlands. These burns encourage new growth for grazing animals and prevent more dangerous fires later in the season.

(Recall from the post every one of those darkly clustered houses that one of the mistakes Captain John Hunter made in settling the First Fleet at Sydney was his failure to recognize that one reason the flora he saw there flourished was a result of controlled burning by the Gadigal People.)

WURRKENG or WURRGENE.

It’s now late June. Fire management continues through August in this even cooler part of the dry season. The creeks that began flowing in Gunumeleng are beginning to dry. The billabongs, now crowded with magpie geese,

[From Picturebirdai.com Photo by GDW45 used under CC BY SA 3.0]

are taking the shape they will have over the coming weeks or perhaps months.

KURRUNG or GURRUNG.

The temperatures are slowly increasing as spring approaches through August and September. The air is dry and temperatures are climbing into the high thirties. It’s a prime time for hunting file snakes and long-necked turtles. Those living close to the shore will look for sea turtles to begin laying their eggs while farther inland, goose hunting continues as does fishing for saratoga and black bream. When the white-breasted wood swallows arrive, it signals that the thunderclouds are not far behind and the year will have come full circle to Gunumeleng.

As it was with my look at the relationship of Australia’s first people to Country, this exceedingly brief overview shouldn’t be read as definitive or comprehensive. It’s more my effort to provide the reader with a basic understanding of the seasons and traditional lives, as I understand them, of the Bininj / Mungguy people whose land I am visiting.