As it can be with other cities it’s tricky to isolate the geology of a continent to a specific area so, before I try to zoom in on Sydney, I’ll begin by taking a brief broader look at Australia’s interesting geologic history starting with where it was before becoming the Earth’s smallest continent. To do that, we need to return once again to Gondwana – a remnant of the supercontinent Pangaea – that I hope you remember from other posts in this series.

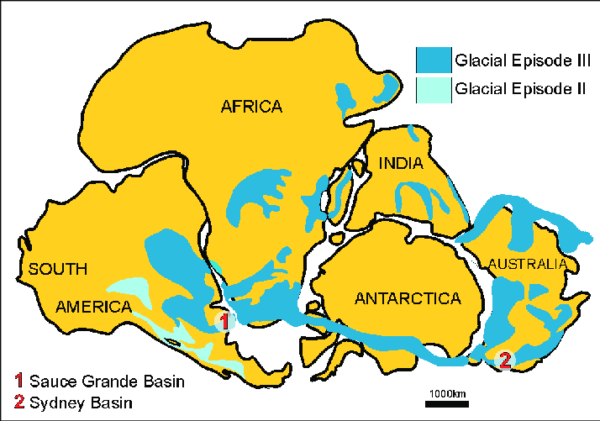

Because the focus of this post is Australia, I’m going to show you Gondwana from a slightly different perspective than I’ve presented in the past.

[From Research Gate uploaded by Gabriela Cisterna]

Remember, Gondwana is a single large landmass so view the map above as a representation of what the continents would eventually look like as Gondwana began to break apart about 180 million years ago (MYA). Although Australia’s shape is similar to the continent as we presently see it, it’s orientation is quite different. It would, in fact, stay attached to Antarctica until about 90 MYA when it began to rotate the approximately 90 degrees necessary to move the Sydney Basin to its present location on the east coast.

As a continent, Australia appears to have undergone a sort of dual formation demarcated by the Tasman Line.

[From Research Gate – Uploaded by John Counts]

Australia to the west of the Tasman Line lies atop ancient cratons and has been relatively stable from a geologic standpoint. This isn’t the case to the east of that line. Beginning long before Gondwana began breaking apart into the constituent continents we see today, terrestrial migrants such as accreting rock fragments also called clasts, terranes, and volcanic arcs along the far eastern edge of Gondwana were laying the foundation for most of eastern Australia.

In addition to the marine and non-marine sedimentary build-up, the east coast experienced several periods of tectonic mountain building called orogenies. For today’s Australia, the most significant of these was likely the Hunter-Bowen orogeny because of its role in forming the Sydney Basin. The initial phase of this event began about 265 MYA and was characterized by periods of accretion followed by rifting and back-arc volcanism (volcanic eruptions happening behind a volcanic island arc or the backside of a subduction zone).

A second major cycle in this orogeny stretched from the late Permian into the early Triassic. During this phase we see arc accretion or the attachment of volcanic islands to the margins of the continent although the volcanoes themselves had stopped erupting tens of millions of years prior. This was also a period of metamorphism (altering a rocks composition by heat or pressure) and significant deformation (thrusting) events. Toward the middle of the Triassic, about 225 MYA, the basin underwent the process of uplift thereby becoming dry land.

[From Wikipedia –By Lencer – own work, used:Generic Mapping Tools and SRTM3 V2-files for reliefMinimap made with Australia location map.svg by User:NNW, GFDL]

Although the process of weathering and erosion continues, the region is geologically stable and the Sydney Basin itself is laterally constrained. On its west it is bounded by the older basement rocks of the Lachlan Fold Belt. If one includes the Gunnedah Basin (the region is often referred to as the Sydney-Gunnedah Basin), the New England Fold Belt stops any potential middle-age spread to the north and east. Parts of the basin remain submerged to the east and south where it extends to the edge of the continental shelf. These were some of the major factors before

The Gondwana breakup.

It might feel like the title of a bad emo song but it’s not. The breakup began about 180 MYA and we’ve encountered it before on our geologic probes but it’s the one that has shaped most of the continents on which our species lives. I’m not one to assign blame but, looking at the direction of the breakup, from this perspective it seems that in this separation Antarctica and Australia somehow offended the other continents even if the time scales are unfathomably long by human measurements.

Look again at the first map. Sure, South America put a lot of distance between itself and Africa but it hooked up with another partner waiting on the western side of the Prime Meridian. Africa and India stayed fairly close and both, one could say cohabit with Asia. All of this action left Australia and Antarctica on their own. And even their relationship only lasted for 80 to 90 million years before they began the separation process. I’d guess that Australia either tired of the polar weather, missed its Gondawanaland mates, or was pushed to the north by tectonic movement. Whatever the cause, it started slowly moving away from its one-time partner at a pace of a few centimeters per year.

Over the next 50 million years or so, the continent became increasingly isolated and this would almost certainly be a factor in minimizing the evolutionary pressure on its native flora and fauna. Although it’s moving, its general geologic stability results from the Precambrian age of its core continental mass and its relative distance from active plate boundaries so not many earthquakes or volcanoes happened there.

On the other hand, the continent seems to like its independence as its northward speed has increased over time and it’s now chugging along at about seven centimeters per year with an interesting impact on human activity.

In truth, this is simply a part of natural plate tectonics. Only the Pacific Plate which is moving northwest at about 10 centimeters per year is outpacing the Australian Plate. It’s worth noting that in addition to its northward flow, the western part of the continent is moving slightly faster than the eastern side. This imparts a bit of a clockwise spin to the continent so someday Sydney might find itself on the southern coast.

By the sea

As the breakup continued, I have to guess that the lawyers got involved because it took 50 million years longer to complete Australia’s separation from Antarctica than Angelina and Brad’s divorce settlement. Granted, there was a lot to settle and some people might opine that the area that would become Sydney lost a lot, it also gained something quite important.

When Australia began moving away from Antarctica 80 MYA, it began forming the Tasman rift. (Rifts are an example of extensional tectonics where the plates in the lithosphere pull apart.) The breakup between the two southern continents is considered complete with the separation of Tasmania from Antarctica 35 MYA and with it, the new ocean basin we call the Tasman Sea. (In more recent times, rising and falling sea levels resulting from glacial advance and retreat would reconnect and disconnect the two islands.)

[From Earthscrust.org.au]

In this process, the area that became Sydney lost about half of the accretionary New England terranes and all of its volcanism to the place that Abel Tasman would name the “new land of the sea” or, as most of the world currently knows it, New Zealand.

So, what did Sydney gain? Beachfront property. For the first time in its history the land that the British would name Sydney was near the sea. I think it’s reasonable to think that without this proximity, the city might have never grown into the major metropolis that positioned it to host the 2000 Olympic Games.