After our visit to the zoo, we were off for a tour of the second of the two icons gracing Sydney Harbour – the Sydney Opera House – which was tabbed as a UNESCO World Heritage site in 2007. It’s interesting to note that controversies surrounded a building Frank Gehry said “changed the image of an entire country.” I think a building that important is worth closer examination.

Goossens Sydney’s growth

In the first half of the 20th century, Sydney’s population tripled to more than 1,500,000 people. Soon after, the city hired renowned British conductor Sir Eugene Goossens

[From Wikipedia – Public Domain]

to lead the Sydney Symphony Orchestra in 1947. He deemed the 1899 Town Hall inadequate and began lobbying for a purpose built concert hall and opera house. Fortunately, he found an ally in Joseph Cahill – the Labor Party Premier of New South Wales. In a 1954 address, Cahill said, “This State cannot go on without proper facilities for the expression of talent and the staging of the highest forms of artistic entertainment which add grace and charm to living and which help to develop and mould a better, more enlightened community. Surely it is proper in establishing an opera house that it should not be a ‘shadygaff’ place but an edifice that will be a credit to the State not only today but also for hundreds of years.”

In 1955, the government chose Bennelong Point to be the site of the proposed venue.

(Bennelong Point was called Tubowgule {‘where the knowledge waters meet”} by the Gadigal People and they had used the resource rich area for uncounted generations before the British arrived and found middens of shells and animal bones that they would crush and use to make a lime slurry. Before it received its present appellation, the British called it Limeburners’ Point.

Woollarawarre Bennelong, {mentioned in the previous post} a member of the Wangal people at the time of the British arrival, was kidnapped by Arthur Phillip, the colony’s first governor. In 1790, Governor Phillip built a brick hut for Bennelong at his request. This is when the point received its name. Bennelong spent the years between 1792 and 1795 in London

[From Bennelong Revealed]

and his brick hut would be demolished after he decided not to resume living at Tubowgule after his return.)

Let the competition begin

Like so many grand public projects, the government of NSW opened a design competition on 15 February 1956. Competitors had to register by paying a fee of 10 Australian dollars, follow the guidelines in the 25 page Brown Book, and submit their entries before the year end. Two hundred twenty-three entries arrived from 28 different countries.

There are conflicting reports about the selection of the winning design. It’s commonly said that Eero Saarinen, the Finnish born American architect, arrived late to the judging and didn’t like any of the three finalists the other members of the panel had chosen and that he was responsible for choosing entry number 218 by an unknown Danish architect Jørn Utzon

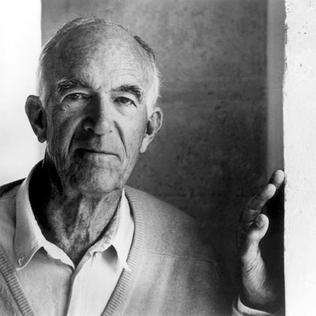

[Jørn Utzon From Wikipedia By National Portrait Gallery, Canberra, Fair use.]

from those previously rejected and declared it the obvious winner. H Ingram Ashworth, another member of the panel has long maintained that a third member Dr J Lesley Martin had also been impressed with Utzon’s design. Regardless, the panel was clearly swayed by Saarinen and, on 29 January 1957, Peter Cahill announced Utzon’s design as the winner.

A pair of architects and a trip to Mexico provided some of the inspiration for Utzon’s design. The architects were Alvar Aalto and the late Gunnar Asplund. Utzon called the Swedish Asplund “the father of modern Scandinavian architecture. Of the pair he said, “Asplund in Sweden and Aalto in Finland possess something beyond pure functionalism. They sometimes display what I would term a spiritual superstructure. It is called poetry. This superstructure makes every house reflect exactly the life in the house.”

In Mexico, ruins of Aztec and Mayan temples gave Utzon the sense that they would have lifted people above their daily lives to a transcendent plateau where they could commune with their gods. Although my presentation is a long way from reaching the finished masterpiece, here’s the element of the building’s interior those temples inspired.

The stairs were intended to replicate the feeling he’d experienced in Mexico. He said, “The opera house should take people from their daily routine into a world of fantasy, a world they can share with the musicians and actors.”

But the waters weren’t always calm

Utzon’s design made full use of the building’s harborside potential using all of Tubowgule by placing the halls side-by-side and cantilevering their shell-shaped roofs over the end of the point. It was a sculptural representation evocative of both Sydney’s cliffs and the sails on the harbor.

Thirty-four years after the building opened in 1973 (yes, a project originally planned to take six years required 16) UNESCO conferred World Heritage status upon it. Here are some of their reasons:

“Its significance is based on its unparalleled design and construction. It is a daring and visionary experiment that has had an enduring influence on the emergent architecture of the late 20th century.

“Utzon’s original design concept and his unique approach to building gave impetus to a collective creativity of architects, engineers and builders. Ove Arup’s engineering achievements helped make Utzon’s vision a reality.”

“The Sydney Opera House is also of outstanding universal value for its achievements in structural engineering and building technology. The building is a great artistic monument and an icon, accessible to society at large.”

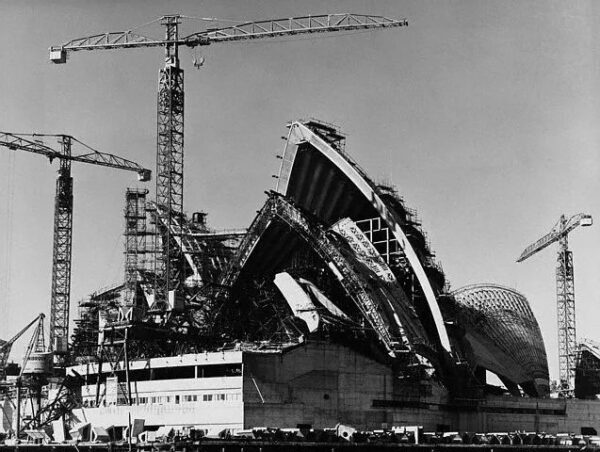

Three distinct stages marked the construction of the building. The first was relatively straightforward. It laid the foundation and substantial podium. The second presented significant engineering challenges and the third became so contentious that Utzon would resign and be replaced by Peter Hall.

The shells were the most challenging aspect of the exterior. The struggle to find a practical engineering solution to the structural instability of Utzon’s design required five years of consultation between the architect, the consulting engineers Ove Arup and Partners, and the Sydney Opera House Executive Committee.

In a moment of serendipity, Utzon hit upon what became known as the Spherical Solution. He realized that each shell was more like the others than unlike them meaning they could be derived from a single constant form such as the plane of a sphere. This meant that not only could the building’s form be prefabricated from a repetitive geometry but it also achieved a uniform pattern for tiling the exterior. It epitomized the fusion between design and engineering.

[From Wiki Arquitectura by Guillermo]

Intractable

(These passions never seem to end.)

The project was already five years past its expected completion. The costs were soaring. And construction of the interior – the third and final stage hadn’t begun. In May 1965, the Labor Party lost an election for the first time in 24 years. The new coalition government appointed David Hughes, the leader of the Country Party as the Minister for Public Works. Hughes refused to pay Utzon $103,000 he was owed forcing his resignation. Despite street protests demanding his return, Hughes remained intractable. Utzon left Sydney with his family on 28 April 1966.

Peter Hall, who accepted the commission only after assurances from the Dane that he would never return to Australia, replaced Utzon. Hall faced a series of significant challenges. He redesigned the foyers in a fusion of his aesthetics and Utzon’s. He had to rebalance the curtains of glass that Utzon had envisioned as appearing suspended from the roof shells to better meet engineering and acoustic considerations.

Perhaps his most substantial contribution was a near complete redesign of the concert hall changing it from a dual-purpose design that could host large scale opera productions in addition to symphonic concerts into a single-purpose design specifically for symphonic music.

A touch of personal tragedy

During and following his work on the Sydney Opera House, Hall saw his contributions devalued by many critics. He died of a stroke on 19 May 1995. Eleven years later the Royal Australian Institute of Architects posthumously awarded him their 25-year award in recognition of his role in completing the Opera House.

Jørn Utzon was true to his promise to Peter Hall. He never returned to Australia even when invited to see his building honored by UNESCO. Utzon died on 29 November 2008 having only seen photos of his masterful achievement – the Sydney Opera House.

Coda

Our tour ended and we boarded a bus to the hotel for a brief rest and an early dinner after which we’d return to the Opera House to see Sarah Brightman in a performance of Sunset Boulevard. Admittedly, while I admire his ability to create popular musicals, I’ve never been a great fan of Andrew Lloyd-Webber. I find him compositionally generic. This show was no exception. On the other hand, the staging was clever and the orchestra brilliant. And I can now say that I’ve seen a live performance in the Joan Sutherland Theatre at the Sydney Opera House.

Tomorrow, we leave Sydney and will fly across the continent to Perth. Here are some photos from the day.

It was an exhausting day! Fighting jet lag!

One exhausting day among many.