Battle Creek – Adventist serial or Adventist cereal? – part 3

When last we saw the Kelloggs, they were fussing about in the kitchen of the San seeking inventive ways to tempt their patients to adhere to the vegetarian dietary principles espoused by its director, Doctor John Harvey Kellogg. The origin story of some sort of small, baked whole grain is generally consistent from various sources, perhaps up to the point of the creation of Granose. When Corn Flakes, the product for which the cereal brand became most famous, is added the tale turns murky.

Doctor Kellogg’s earliest concoction, inspired when a female patient broke her tooth on a biscuit version of a similar recipe, was a twice-baked mix of flour, oats, and cornmeal that he smashed into small bite-sized pieces. He believed that baking whole grains at high temperature made them more easily digestible which, in turn, made them healthier.

The transformation of the smashed bits into what would become corn flakes, started accidentally when a batch of overlooked wheat based dough sat unnoticed long enough to begin fermenting. Someone rolled the slightly moldy dough into thin sheets that, when subjected to the high temperatures, produced thin flakes. This new formulation seems to have advanced John Kellogg’s goal of producing an easily digestible, pre-made, healthy breakfast food he could serve to patients in the Sanitarium.

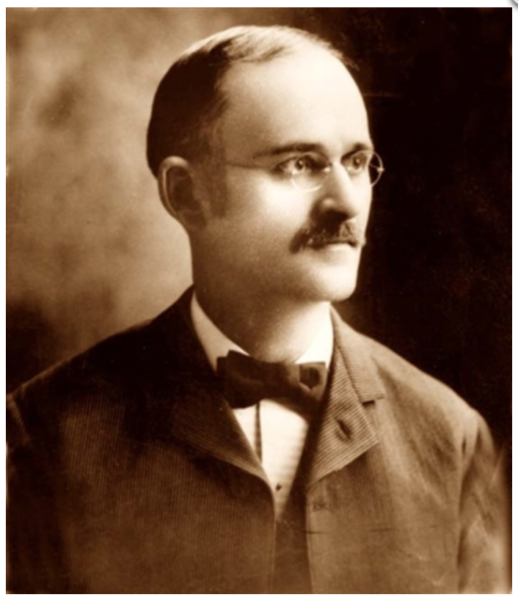

It’s at this point that the origin story begins to blur. First, both John’s wife Ella

[Ella Kellogg – photo from SDA Encyclopedia.]

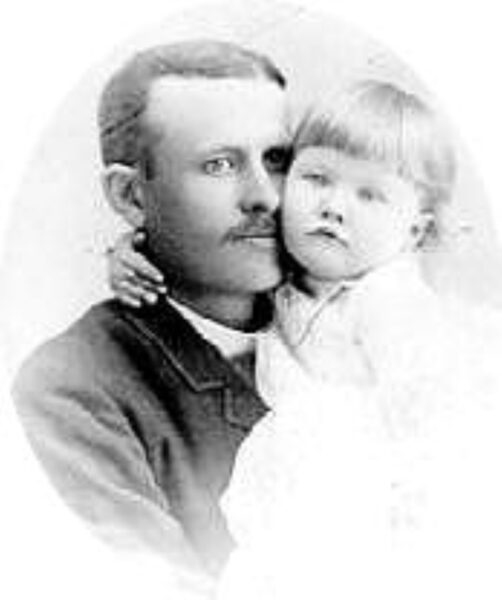

and brother Will

[Will Kellogg photo from Pinterest.]

lay claim to having played significant roles in the invention of the flakes. They certainly worked in the kitchen with him and Will helped design the cereal roller that was an essential part of the process. (Another person in the kitchen was an indigent patient named Charles William Post who was working there to pay his bill.┬Ā Look for his antagonistic reappearance later in our story.) As the patients expressed a taste for this product over many other of the particularly bland offerings that emerged from the San’s kitchen, Will, who already had a contentious relationship with his older brother, sensed a commercial opportunity.

Over a period of several years, as the brothers shipped flakes to discharged patients almost as fast as they could produce them, Will began kneading and refining the recipe. He discovered rather quickly that corn-based dough created a crispier, more appealing flake than wheat dough. When Will added malt, salt, and sugar to the recipe, it was essentially the last straw for John who believed that, like alcohol, sugar was a vice to be avoided. This drama ended when Will bought the rights to the cereal recipe, struck out on his own, and founded the Battle Creek Toasted Corn Flake Company in 1906.

The low Post.

When C W Post arrived at the Battle Creek Sanitarium sometime between 1892 and 1894, he was both sickly and destitute. He worked in the kitchen to pay the fee for his treatment. Whether Post was merely shrewd and observant in his time in the kitchen or whether he actually stole some of Kellogg’s recipes is another murky matter.

Where there is no debate is that Post established the Postum Cereal Company in 1895 and that his company’s first three products – Postum, Grape Nuts, and Post Toasties (originally called Elijah’s Manna) – bore uncanny resemblances to Kellogg’s Carmel Coffee Cereal, Malted Nuts, and Corn Flakes. Thus, by the time Will Kellogg set out to build his cereal business, Post, seen here with his daughter Marjorie Merriweather Post,

[Photo – Wikimedia Commons – Public Domain.]

proved to be a formidable competitor. In fact, Post went so far as to purchase exclusive rights to manufacture the cereal-rolling machine needed in the production process – the very machine Will Kellogg had helped design.

However, Will understood the power of the Kellogg name and by investing heavily in advertising

he was soon going toe to toe with Post’s company and some 80 others in Battle Creek’s “cereal boom” of the first decade of the twentieth century. By 1910, Post and Kellogg’s, together with Ralston, an interloper from the St. Louis area, more or less ruled the American breakfast cereal market.

The downside of Will’s success was that his use of the name didn’t sit well with imperious, domineering older brother, John, who was also selling cereal under the company name Sanitas that they had established together.

John had replaced Will’s name with his own. The competition triggered competing lawsuits with Will filing first claiming that John’s name diminished the brand he’d spent millions of dollars advertising. (In 1909, Will cleverly added a coloring book as a child’s toy to his boxes of cereal. The space used by the book displaced the space available for the cereal thereby increasing his profit margins.)

John Harvey countersued claiming his fame as a doctor lent credibility to Will’s products and wanted to bar him from using the family name. Will won the first case when the Michigan Supreme Court ruled in his favor and limited John Harvey to putting his name in only a small notification on his boxes. A second lawsuit settled in 1920 granted Will international naming rights.

According the Howard Markel’s book The Kelloggs: The Battling Brothers of Battle Creek,

After the court case[s]ŌĆ” they rarely spoke to one another. Their last face-to-face meeting was a terrible argument, and John died only a few months later. ItŌĆÖs really quite sad. John did try to make amends, but Will would have none of it. They both went to their graves very sad about how acidic this relationship became.

Different paths, similar personalities.

As the first decade of the twentieth century wore on, John Harvey grew uncomfortable with some changes in the philosophical underpinnings of the SDA church and the Church became uncomfortable with some of Doctor Kellogg’s more liberal scriptural interpretations, other views they saw as problematic, and some of his treatments (such as the previously described yogurt enemas) at the San.

Theologically, as the SDA moved toward a more trinitarian religious philosophy, Kellogg rejected Christian fundamentalism and advanced a more pantheistic worldview. After a 1902 fire destroyed the Sanitarium and created┬Ā massive debt for the under-insured property, Kellogg, in opposition to the views of Ellen White, oversaw its rebuilding. He would be expelled from the Church in 1907.

John Harvey had a number of other problematic views outside the Church as well. While serving on the Michigan State Board of Public Health,┬Ā for example, he lobbied for a law to sterilize “mentally defective persons” that resulted in more than 3,800 such involuntary procedures.

In 1902 he joined with Irving Fisher and Charles Davenport to establish the Race Betterment Foundation with the intended purpose of maintaining the superiority of certain races through selective breeding. Later, this organization partnered with the Eugenics Record Office to trace families for the purposes of eugenics. It ceased operating in 1935. John Harvey Kellogg died in 1943.

Meanwhile, Will, who had suffered significant abuse at the hands of his brother since childhood, went about successfully appropriating many of John Harvey’s cereal recipes to build his business. (According to Markel, John Harvey humiliated and browbeat his brother for their entire lives. When they were children, his attacks were both physical and verbal. As adults, the doctor treated him like a lackey even though Will was quite successfully administering the Sanitarium’s business. He paid him poorly and humiliated him in front of the guests. The doctor would ride his bike {chainless so as not to stain his ubiquitous white suits}

across the campus and force Will to run beside him taking notes so as not to miss a beat of his brilliant ideas.)┬Ā

It may be that a sense of self-deprivation had generated Will’s outer insecurity and the years of abuse at the hands of John Harvey created a man who was reportedly domineering but who also demonstrated a deep inferiority complex. Perhaps to make up for this, he showed a great sense of support for his community and exceptional generosity.

In 1925 he decided to “invest his money in people” asking three friends to organize the Fellowship Corporation to study the needs of children in the community. He founded the W K Kellogg Foundation in 1930 and made a remarkable donation of $66,000,000 to it in 1934. (Its 2023 equivalent would be about $1,500,000,000.)

Throughout the Great Depression, the demand for cereals remained high because they provided a relatively affordable nutritious meal. Because production didn’t slow, Kellogg further assisted and stabilized his community through this period by keeping wages relatively stable, adopting a six-hour work day, and adding a fourth shift thereby increasing the factoryŌĆÖs work force by 25 percent.

In an interview with the Knowledge at Wharton podcast, Markel noted that Will was never terribly happy and was so domineering that when he died, his grandson wrote, “Nobody really shed a tear.”

The day continues with a visit to the site of one of the darkest events in Michigan history in the next post. Meanwhile you can see the rest of my photos from my visit to the Adventist Village here.┬Ā

-

It’s just a shot away – Prizren

March 6, 2026 -

Some things looking better, baby – Getting into Kosovo

March 4, 2026 -

Here, where the sky is falling – Kuk├½s

March 2, 2026 -

That’s when we fall in line ’cause we got Berat

February 27, 2026 -

Walking on the big stuff – a climb to Tragjas

February 25, 2026

3 responses to “Battle Creek – Adventist serial or Adventist cereal? – part 3”

Is Merriweather Post Pavilion named after the young gal?

It is indeed. She also left behind the Hillwood Esstate and Gardens in Washington DC and built a little place in Florida called Mar-A-Lago.

Lots of money in Corn Flakes evidently!