Before we were distracted by the glacier, I was describing the eventual breakup of what historians refer to as the Kalmar Union and we had taken a temporal trip to November 1520 and the Stockholm Bloodbath. So, as we get back on the bus heading toward Geirangerfjord and the town of Geiranger (quick pronunciation approximation reminder – GAY-RAhN-grr), the northernmost location we’ll visit on this trip we’ll take another dip in the icy waters of Scandinavian history.

A significant element of that history is intertwined with the Reformation which, of course began when, protesting the sale of indulgences, Martin Luther wrote what became known as The Ninety-Five Theses in 1517. Luther’s work probably reached Denmark, which was at that time the power center of Scandinavia, sometime in the early 1520s. Both Christian II and his successor, Frederick the First who deposed him in a coup, tolerated the spread of Lutheran ideas though the latter officially condemned them.

Frederick’s son, who became Christian III, was more zealous in embracing the reformist ideas introducing them into his possessions by 1528. After Frederick’s death, Christian was elected king in 1533 by a group of nobility in Jutland. However, Christian II still had his supporters and this triggered a civil war in Denmark known as the Count’s Feud that lasted from 1534-1536.

[Siege of Copenhagen 1536 – image from Wikipedia – Public Domain.]

I mentioned that Gustav Vasa (King Gustav 1 of Sweden) had essentially led a successful rebellion against Christian II, had been proclaimed king of Sweden in 1523, and was eventually crowned in 1528. Well, during this time, Vasa was steering Sweden toward Lutheranism and, though the official break with the Catholic Church wouldn’t occur until 1536, he began confiscating Catholic Church property as early as 1527. This is important because Vasa came to Christian III’s aid during the Count’s Feud securing a key victory in the town of Helsingborg (just across the sound from Helsingør in today’s Denmark) that allowed Christian III to emerge triumphant. This didn’t prove to be much of a boon for the peasant classes in Denmark who saw the rise of royal absolutism arise under his rule.

One other significant consequence of the Count’s Feud had its seeds sown in the invitation from the Danes for the Swedes to enter the southern peninsula of SkĂĄne. The territory was, at the time, considered part of Denmark and the Swedes handed it back to the Danish King. However, their victory there gave them cause to think they might be militarily strong enough to grab some additional territory for themselves.

Over the next nearly century and a half, Sweden engaged in a series of wars with Denmark taking particular advantage of the Danish involvement in the Thirty Years War (1618-1648) to chip away at Denmark’s power and territory while increasing their own. These decades of skirmishes culminated with the Dano-Swedish War in 1658-1660. The Treaty of Copenhagen settled this conflict and, with the Swedes essentially trading the island of Bornholm for territory in SkĂĄne, the treaty essentially established the Scandinavian borders that exist today.

Wondering where poor Norway is in all of this (since that’s the country we’re driving through)? Well, poor Norway was still recovering from the Black Death and was, as our guide Frederick often described it, “down and out.”

We’ll leave Norway and the rest of Scandinavia in the 17th century for now because the bus has lined up for our ride on the ferry from its departure point in Hellesylt through the Geirangerfjord to our eventual stop at the town of Geiranger and the Hotel Union.

Geirangerfjord, which is 15 kilometers long, is a branch of the Storfjorden system, and was declared a natural UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2005. In addition to the inherent spectacle of the fjord, Geirangerfjord is famous for the Seven Sisters waterfalls which are faced on the opposite side of the fjord by a waterfall called The Suitor. It’s also known for its ladder farms frequently perched seemingly inaccessibly high on the cliff faces towering above the water.

The fjord itself is fairly narrow and for most of its length there is, as you can see in the photo, no shore area. Yet somehow, cruising the fjord, you look up and see something like this:

(Remember, only two percent of Norway is arable.) If you look closely at the right hand side of the picture, you can see a rope used to transport supplies (whether it is still manually or now electrically operated, I don’t know) running down from the building. Frederick told us the farms are accessible by paths winding around steep precipices and bridges that are fixed to the mountains by iron bolts and rings.

Some of these farms had their earliest habitation in the 17th century. One, just south of the Seven Sisters waterfalls near the village of KnivsflĂĄ, was abandoned in 1898 because of the danger of rockslides but the farm and a grazing pasture some 500 meters or so above the fjord can still be accessed by a path that I didn’t see from the ferry. On the side opposite the Seven Sisters is another farm called SkageflĂĄ that sits 250 meters above the fjord. This one was abandoned in 1916 though it is said to have once been one of the richer goat farms in the area and may be the one in the picture above.

The longest free fall of the seven streams that comprise the Seven Sisters is also 250 meters making it the 39th highest in Norway. The legend of the seven sisters and the single companion “suitor” on the opposite side of the fjord is that the former dance down the mountain while the latter flirts with them. You can (barely) see all seven streams in this photo.

Before I close today’s entry, I have to include a few words about the Hotel Union. Like many hotels in this part of Norway, the Hotel Union is a family operated inn and, in this case, has been operated by the Melva family since 1897. In the early 20th century, the hotel became quite popular for many among the well to do in Europe and in the United States. Norway saw an increase in wealthy Americans cruising to its west coast particularly after the American Congress passed the Emergency Quota Act in 1921. Ship owners whose fleets had been carrying immigrants across the ocean looked to make money by re-purposing those fleets.

(This act which restricted the number of immigrants annually admitted from any country to 3% of the number of residents from that country living in the United States as of the 1910 Census. Though not explicitly stated, its intent was to restrict the number of Europeans from the southern and eastern reaches of that continent. For the first time in the country’s history, American immigration law now not only placed numerical limits on immigration but established those limits by using a quota system.)Â

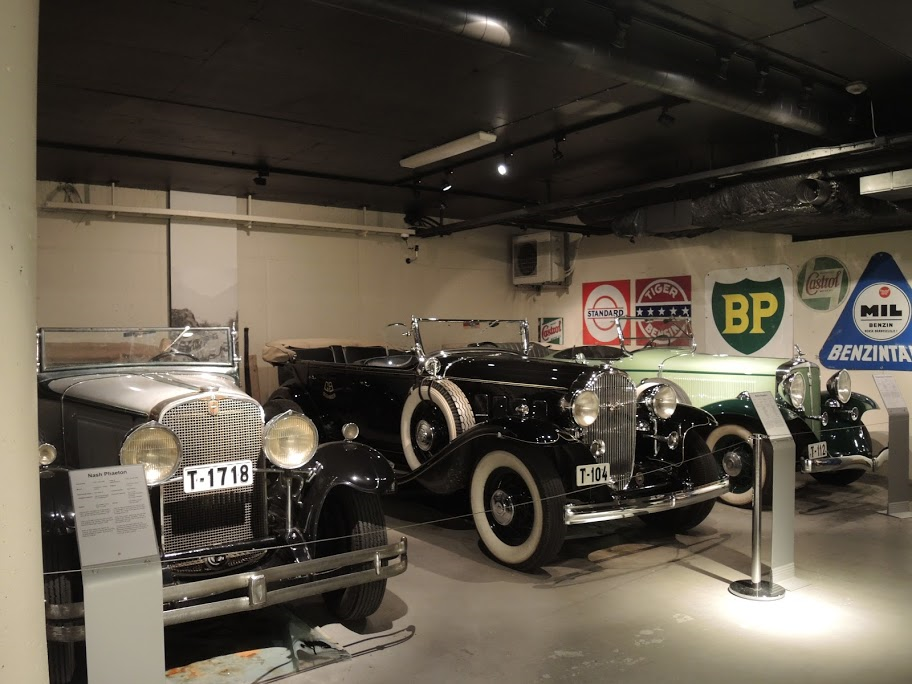

To cater to this new influx of tourists, the hotel began purchasing luxury cars. Nine of these now vintage and classic cars – all of which are still in running condition – are on display in the hotel. One is in the lobby and the remaining eight are in a dimly lit room at the back lower level of the hotel behind its conference center. As I looked at these vintage Nashes, Studebakers, and the like, I spent considerable time thinking about my late brother who had such a passion for cars in general and classics like these in particular. This one’s for you, Steve.

Nice tip of the hat for Steve! And fun to read about Bornholm in today’s writing. I sure love that island!

Steve gets a hat tip whenever possible. But nothing to say about my pun?